Hunger is an issue that has long plagued a number of countries in Southeast Asia. Cambodia, a developing country between Thailand and Vietnam, remains one of the poorest nations in the region.

But, in recent years, Cambodia has made notable progress towards improving citizens’ nutrition. This can be seen from the reduction of children’s stunting occurrences (low-height-for-age) from 42 percent in 2005 to 32 percent in 2014. The kingdom’s poverty rate had also decreased from 53 percent in 2004 to 13.5 percent in 2014. It is now expected to be below 10 percent.

Since the end of the Khmer Rouge in 1979, organisations such as Action Against Hunger and the World Food Programme (WFP) have helped vulnerable Cambodians “meet their emergency needs and have access to nutritious, safe and diverse foods.” Moreover, in a bid to meet its goal of ending hunger in the kingdom by 2030, the government in collaboration with the WFP created programmes to promote access to nutritious diets within Cambodia. An example of this is the WFP-supported home-grown school feeding programme.

Despite the progress, a 2018 World Vision report noted that the number of Cambodian children under five suffering from malnutrition has remained high with 32 percent of them showing signs of stunting, 24 percent being underweight and 10 percent being wasted.

In the “Ending Malnutrition in Cambodia Is Possible” report, the organisation cited diarrhoea as a result of poor sanitation in households and the community as the primary cause of malnutrition in the kingdom. When children experience repeated bouts of diarrhoea accompanied by food that has low nutritional value, they can become chronically malnourished.

However, with the coronavirus pandemic which has severely affected livelihoods across the globe, the problem of malnutrition in Cambodia appears grimmer.

Nutrition Affected

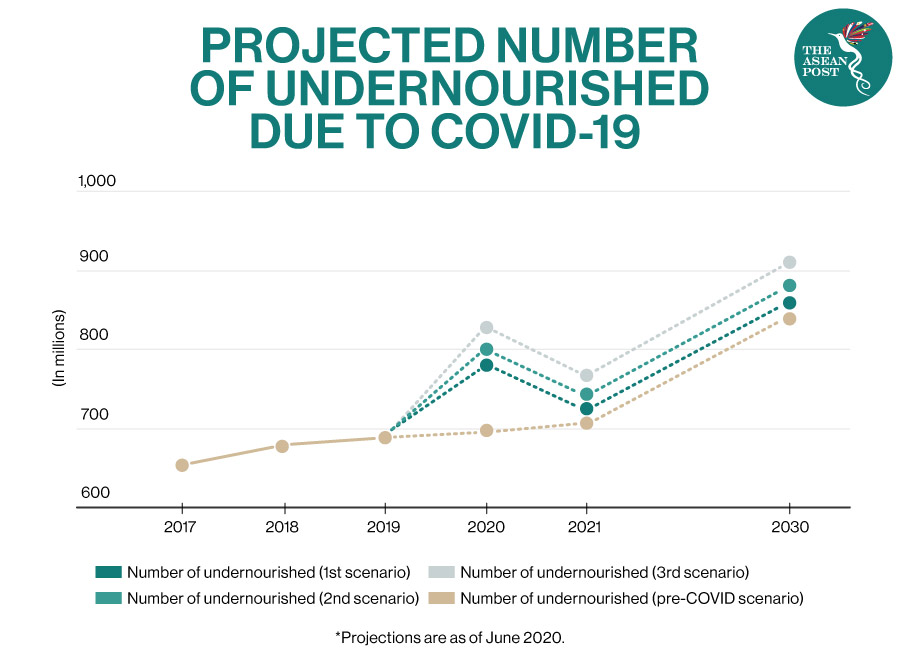

The “State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World” report published in July 2020 by the United Nations (UN) states that nearly 690 million people went hungry in 2019, or 8.9 percent of the world’s population. This is an increase of 10 million from 2018 and 60 million in five years. The report also expected the pandemic to tip over 130 million more people into chronic hunger by the end of 2020.

A more recent joint-report released by UN agencies – the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF), Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), the WFP, and the World Health Organization (WHO), stated that the pandemic is threatening access to a healthy diet for nearly two billion people in the Asia-Pacific region.

Malnutrition is simply the result of not having enough to eat. However, a child or an adult can have enough food to eat and still be poorly nourished if they do not eat the right foods at the right times.

Titled “Going hungry – how COVID-19 has harmed nutrition in Asia and the Pacific,” the report noted that more than half of households in Cambodia have at some point had to cut back on the size and quantity of their meals as an effect of the pandemic – causing setbacks in the fight against malnutrition.

Sometime early last year, food prices particularly for meat, eggs, and fish products in Phnom Penh, and fresh vegetables in provincial markets – increased. Although prices have since stabilised, many households decreased their food intake and diet diversity in important food categories such as products rich in protein, vitamin A and iron.

The report stated that in August 2020, 30 percent of Cambodian women’s diets failed to reach minimum diversity. Unfortunately, this then increased to 50 percent by November.

“Malnutrition has been a long-term challenge in Cambodia, one recognised by the government and its development partners. Much progress has been made in the last decade, but COVID-19 is putting that progress in jeopardy,” said Foroogh Foyouzat, UNICEF’s representative in Cambodia.

Echoing UNICEF, the FAO also stated that dealing with COVID-19 has led to setbacks in the fight to end hunger and malnutrition, despite some countries in the region including Cambodia having only recorded double to triple-digit COVID-19 infections.

Back in September 2020, FAO offices in Cambodia and countries in the Asia-Pacific region participated in a four-day virtual conference to address the “twin pandemics” of COVID-19 and hunger facing the region.

“We must come to terms with what is before us and recognise that the world and our region has changed,” said Jong-Jin Kim, FAO’s regional representative for Asia and the Pacific.

“We must find new ways to move forward and ensure sustainable food security in the face of these twin pandemics, as well as prepare for threats that can and will evolve in the future,” he continued.

As an effort to reduce hardship and meet needs, the government of Cambodia expanded its social cash transfer programme to more than 600,000 of its most vulnerable citizens.

However, as stated in a joint press release by UN agencies, “more investment is required to further expand social assistance and ensure improvements are made to food systems to increase access to nutritious foods, boost productivity, improve food safety, and protect employment, while stimulating demand for domestically produced foods.”

Related Articles: