Early this year, a 16-minute documentary called “Lost World” was released. The documentary, directed by Kalyanee Mam and produced by Go Project Films, the John D and Catherine T MacArthur Foundation, and Heinrich Böll Stiftung, showcases the damage done to Cambodian coastal fisheries by the industrial-scale dredging of sand for sale. Lost World eventually won the Sundance Grand Jury Prize for Feature Documentary.

Today, the practice has largely been shut down in Koh Kong, the area featured in the film. Unfortunately, sand mining continues in other parts of Cambodia and throughout Southeast Asia. One of the places this dredging continues is in the mighty Mekong River.

Originating in the Tibetan highlands and running through China, Myanmar, Thailand, Lao PDR, Cambodia, and Vietnam, the Mekong and its tributaries provide water, food and income for 60 million people. The longest river in Southeast Asia is home to the world’s largest inland fishery. It is estimated that 25 percent of the world’s freshwater catch is harvested from this river.

But the Mekong faces a host of threats, from China’s dam-building along the waterway to the indiscriminate dredging of sand. In the latter, Cambodia must shoulder a large portion of the blame.

Sand dredging is big business in Cambodia. While numbers vary - showing a lack of transparency on the matter – most statistics show that Cambodia is one of the largest exporters of sand in the world. In 2015, Cambodia was placed at number seven on the list of top 20 sand exporting countries, garnering the country more than US$53 million in income.

A more recent list from the World’s Top Exports (WTEx) reports a more conservative figure of US$34.6 million in 2018. Nevertheless, Cambodia still sits comfortably at seventh place compared to 15 other countries. In fact, the WTEx states that Cambodia is one of the fastest-growing sand exporters since 2014 – up by 4,620 percent!

Dredging of sand in the Mekong and other waterways in Cambodia and Lao has far reaching implications. An article published by National Geographic in April noted that environmentalists have expressed concern that dredging is causing river banks to collapse, dragging down crop fields and even houses.

“Farmers in Myanmar say the same thing is happening along the Ayeyarwady River. In Malaysia, villagers complain that sand mining is damaging two key rivers,” the National Geographic wrote.

Back in Cambodia, the Borgen Project has noted that there is a link between sand dredging and poverty. This isn’t hard to imagine as sand mining also has an adverse effect on fish habitat.

“The connection between sand mining and poverty in Cambodia is seamless. The known dredging concessions were in Koh Kong and Preah Sihanoak provinces on Cambodia’s western shore. People in the fishing villages were not consulted by the companies or informed by local authorities before operations began. In the village of Koh Sralau, sand dredging has ravaged the ecosystem that thousands of families depend on for their livelihood,” the Borgen Project wrote.

As noted earlier, the Mekong and its tributaries provide water, food and income for 60 million people. Meaning that sand dredging could potentially affect the livelihoods of that large number, more than thrice the total population of Cambodia as of 2019.

There is a huge concern. However, Cambodia has no intentions of stopping its sand dredging activities anytime soon.

On Friday, it was reported in Cambodian media that, according to VTrust Appraisal, Phnom Penh will see a steady rise in the supply of condominium units in the next 10 years, reaching 295,000 units in 2030. Hoem Seiha, VTrust Appraisal research director, said that, on average, the supply will grow by 19,000 units per year.

The National Geographic noted that in addition to Cambodia’s own city-building needs, there are potential customers in large-scale land reclamation projects underway all-over eastern Asia.

“Hong Kong is just getting started on an US$80 billion initiative to create at least 2,500 hectares of artificial islands – which will be built largely with imported sand.”

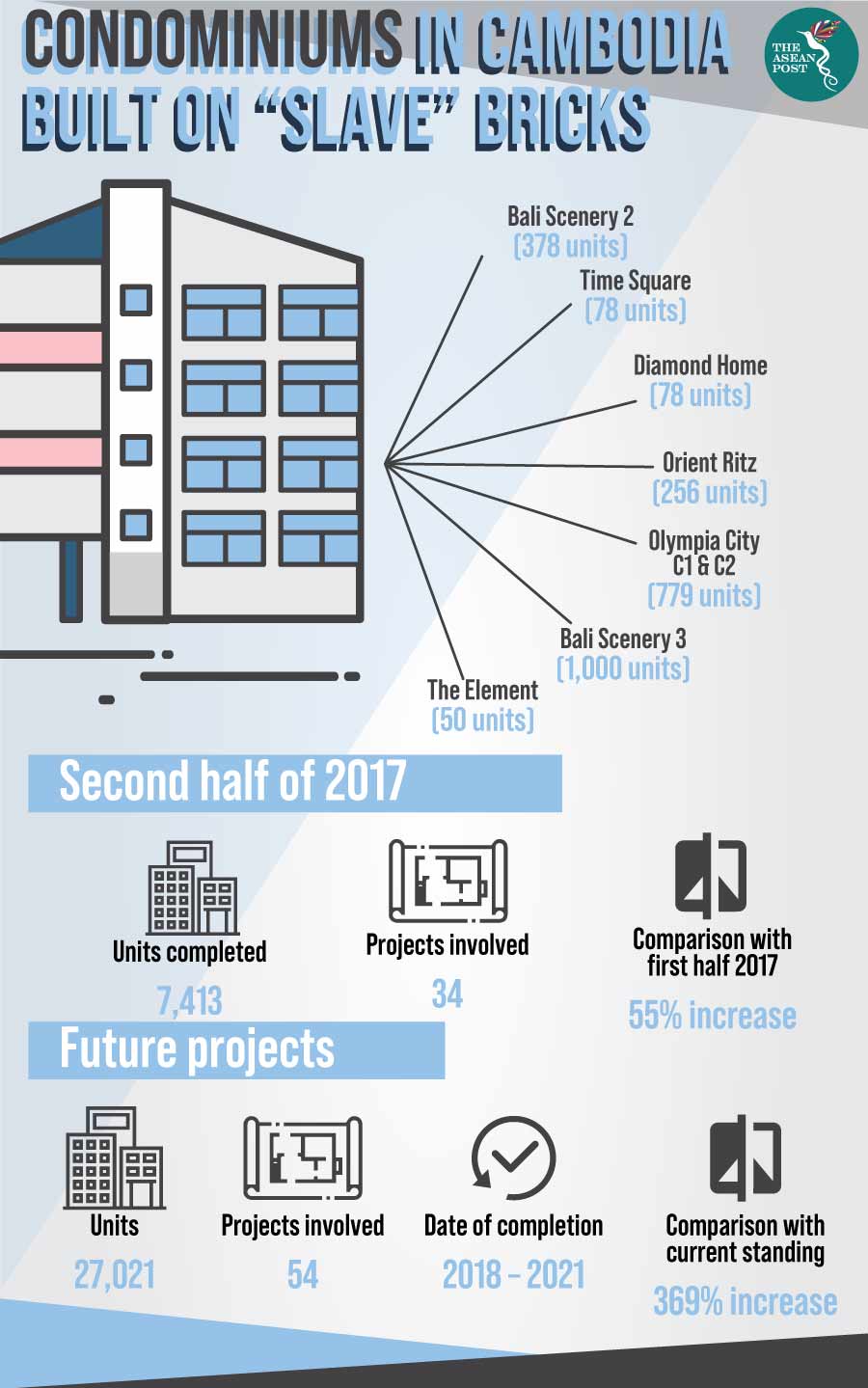

According to Knight Frank’s Cambodia Real Estate Highlights for the second half of 2017, 7,413 units of condominiums across 34 projects were recorded. This is an increase of 55 percent compared to the first half of the year.

Out of 7,325 units across 26 projects scheduled for completion by the end of 2017, seven projects providing 2,619 units were completed. 64 percent of anticipated supply rolled over into 2018. The seven projects included Bali Scenery 2 with 378 units; Time Square with 78 units; Diamond Home 1 with 78 units; Orient Ritz with 256 units; Olympia City C1 & C2 with 779 units; Bali Scenery 3 with 1,000 units and The Element with 50 units.

54 projects providing 27,021 units were identified within future stock due for completion between 2018 to 2021, resulting in an increase of 369 percent.

United States (US)-based Public Broadcasting Service (PBS) recently quoted Boston University biologist Les Kaufman as saying that inland sand is too fine-grained and not suited to make concrete.

“So, there's this big incentive to mine it out of water, out of freshwater or the ocean,” he was quoted as saying.

Cambodia has set its sights on meeting the demand of those that may be interested in importing sand from Cambodia. Hence, the damaging sand dredging will continue. Unfortunately, and as is often the case, the price of development might end up becoming too costly to bear.

Related articles: