On 9 November, Cambodia celebrated its Independence Day. But while most Cambodians were celebrating their freedom from the control of the French Protectorate of Cambodia, thousands of other unfortunate Cambodians are still working in brick kilns throughout the country. “Freedom” for these people is just an empty promise.

A recent Blood Bricks research project has led to a photo exhibition exposing debt-bonded labour in the brick making industry. While the photos show glimpses of just what life may be like for adults and children forced to work under horrific conditions, they also seek to prove that modern slavery should be looked at as a structural problem fostered by global commerce and growth.

The Blood Bricks research project was conducted by Laurie Parsons, a researcher at the Royal Holloway, University of London who has been studying Cambodian livelihoods since 2008 with her colleagues. A likely-frustrated Parsons wrote that despite the immediate impact, these and other images in the long run tend to be compartmentalised; placed in a box marked “out there”, too far from the West’s everyday experience to relate to.

“After all, it wasn't too long ago that Cambodia's capital city Phnom Penh was a ghost town, forcibly evacuated by the Khmer Rouge of its two million inhabitants and left as an eerie wasteland: empty, silent and rapidly returning to nature,” she said.

Building bricks

Parsons concerns about modern slavery seems to have its roots in the issue of supply and demand. She puts forth the argument that it is in fact the West which is propagating modern slavery in less developed parts of the world like in Cambodia, and that it is doing so due to demand for infrastructure and development in the country.

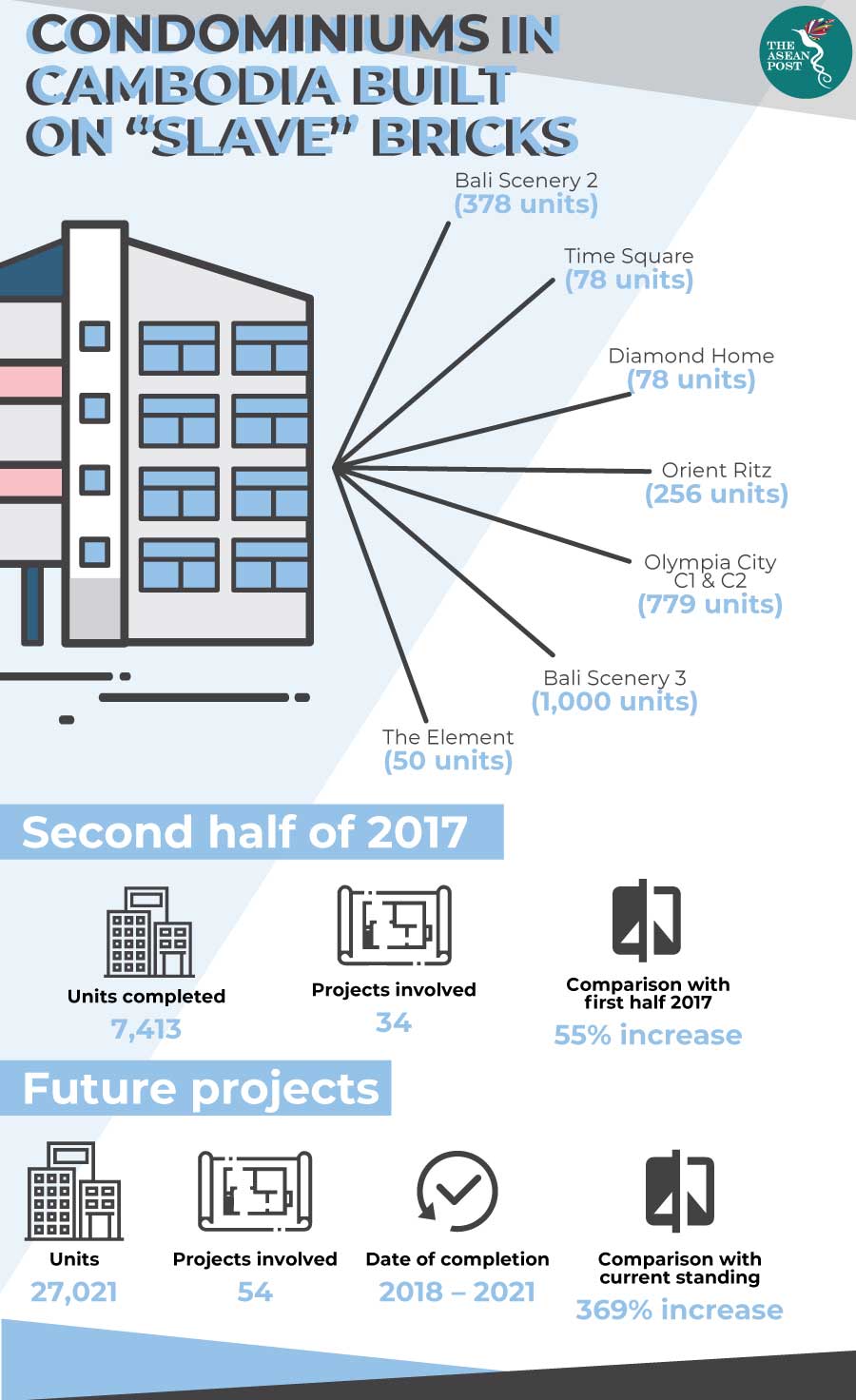

According to Knight Frank’s Cambodia Real Estate Highlights for the second half of 2017, 7,413 units of condominiums across 34 projects were recorded. This is an increase of 55 percent compared to the first half of the year.

Out of 7,325 units across 26 projects scheduled for completion by the end of 2017, seven projects providing 2,619 units were completed. 64 percent of anticipated supply rolled over into 2018. The seven projects included Bali Scenery 2 with 378 units; Time Square with 78 units; Diamond Home 1 with 78 units; Orient Ritz with 256 units; Olympia City C1 & C2 with 779 units; Bali Scenery 3 with 1,000 units and The Element with 50 units.

54 projects providing 27,021 units were identified within future stock due for completion between 2018 to 2021, resulting in an increase of 369 percent.

A developed Cambodia

Developed countries gain from their import destinations that experience increased development. This is especially true when it comes to development in infrastructure.

A number of studies have found empirical support for the positive impact of infrastructure on the aggregate output of a country. Aggregate output here is the total amount of output produced and supplied in the country for a given period of time.

In a seminal paper, David Alan Aschauer from the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, found that the stock of public infrastructure capital is a significant determinant of aggregate total-factor productivity (TFP), or the portion of output not explained by traditionally measured inputs of labour and capital used in production.

Parsons claims that in Cambodia, the much-celebrated urban turnaround is rooted firmly in international investment to which the United Kingdom (UK) is a significant contributor. She found that British companies have a stake in many of these buildings and help to construct many more, adding that UK imports more than US$1 billion worth of goods from Cambodia each year, making it Cambodia’s largest European trade partner.

“British consumers, like those in many other Western nations, therefore benefit from cheaply made goods made in countries to which they pay little attention,” she says.

If imports from the developed world are indeed propagating the modern slavery that allegedly exists in Cambodia’s kilns, then the European Union’s (EU) threat to suspend its Everything But Arms (EBA) trade deal with the ASEAN member state could, ironically, become a saving grace for many Cambodian brick-makers. However, while the EU remains Cambodia’s largest trading partner, several countries including China and more recently, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), may nullify the effects of the EU pulling out. More than likely a solution will have to come from within The Kingdom itself and a key ingredient to that seems to be political will.

Related articles: