Recently, on 30 August, the world witnessed the International Day of the Victims of Enforced Disappearances. International law defines enforced disappearance as the detention of a person by state officials and a refusal to acknowledge the detention or to reveal the person’s fate or whereabouts.

The United Nations (UN) states that enforced disappearance has frequently been used as a strategy to spread terror within a society.

“The feeling of insecurity generated by this practice is not limited to the close relatives of the disappeared, but also affects their communities and society as a whole,” it says.

Two days later, on 1 September, Human Rights Watch (HRW) Asia Director Brad Adams wrote an article on HRW’s official website, claiming that this year’s International Day marked yet another year Thailand has failed to fulfil its pledges to outlaw the “heinous practice”.

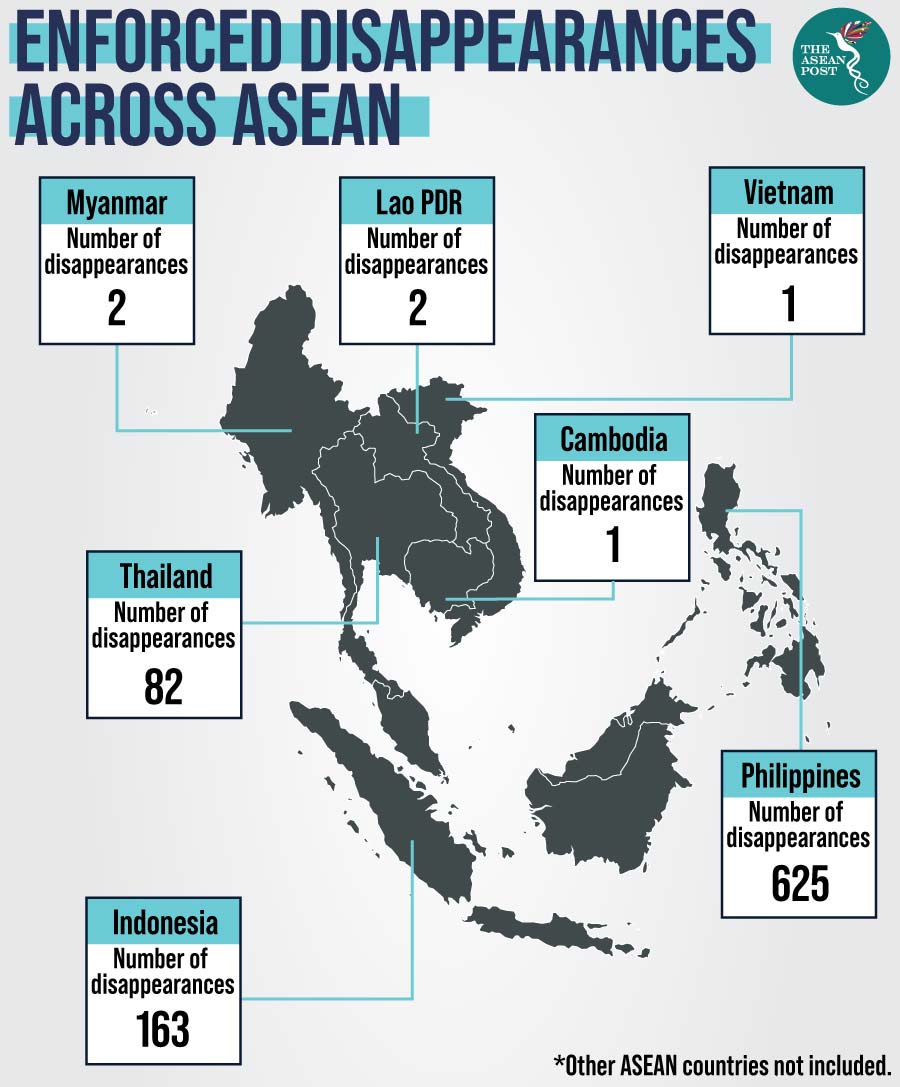

“The United Nations Working Group on Enforced or Involuntary Disappearances recorded 82 cases of enforced disappearance in Thailand since 1980, including that of prominent Muslim lawyer Somchai Neelapaijit in March 2004. Human Rights Watch believes the actual number is higher, as some families of victims and witnesses remain silent, fearing reprisals by the authorities if they speak out,” he wrote, adding that none of these cases have been resolved, and no one has been prosecuted.

Somchai was a Thai Muslim-lawyer and human rights activist who "disappeared" on 12 March 2004 during Thaksin Shinawatra's regime. He was last seen on that date in Ramkhamhaeng where eyewitnesses saw four men dragging him from his car.

Ousted Thai Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra is believed by many interested in the case to have played a part in Somchai's disappearance and probable murder. Though his body has not been found, the motive is thought to have been Somchai's representing Muslim defendants in terrorism cases. The day after Somchai's disappearance, concerns were publicly raised.

Draft law

A draft law on preventing enforced disappearances is currently in parliament. In 2017, lawmakers from the military-led National Council for Peace and Order (NCPO) returned a draft of the law to cabinet for more consultations, and the government told the UN Human Rights Committee that year that it was delaying passing the bill to review it and hold public consultations. The Cabinet returned a new draft to parliament on 18 July 2019.

Amnesty International has highlighted the urgency of passing the law after amending it to comply with Thailand’s law obligations. The human rights body noted that the Thai authorities signed the International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance in January 2012, but progress on ratifying the Convention and passing domestic legislation have been repeatedly stalled.

“By its inaction, Thailand has allowed a shocking blind spot to prevail in its legislation. The result is that Thai citizens may be tortured, or subject to enforced disappearance, while authorities are not fully equipped to pursue those responsible,” said Piyanut Kotsan, Director of Amnesty International Thailand.

Somchai’s wife Angkhana Neelapaijit who is also part of Thailand’s National Human Rights Commission says that the draft law must be toughened up as it is currently focused on “protecting government officials.”

“The state must stand with the victims,” she says.

On 12 March recently, marking 15 years since Somchai disappeared, Angkhana was quoted as saying that bringing perpetrators to justice could not be ignored, no matter where on the ladder the government official stood.

“The families of the disappeared — including myself — are still waiting for justice,” she said during the memorial event at the Netherlands Embassy in Bangkok.

Thailand is certainly not the only ASEAN country guilty of enforced disappearances and isn’t even the worst. According to statistics from the United Nations Working Group on Enforced or Involuntary Disappearances, Philippines takes the top spot as far as the number of cases involving enforced disappearances since the 1980s goes.

However, to compare itself to other countries worse off countries would be missing the point. Enforced disappearance means that a country’s people can no longer trust the very same individuals put in power to protect those people in the first place. Because of this fact, even one case of enforced disappearance is one too many. Thailand has over 80.

Related articles: