The ASEAN Post recently published an article on the possible real victims of Philippines President Rodrigo Duterte’s “War on Drugs”. In that article, we cited a study conducted by researchers Abbey Pangilinan, Maria Carmen Fernandez and Nastassja Quijano in which they argued that hundreds of families have plunged deeper into poverty as a result of the Philippine drug war.

An important point noted in that study was that the death of the male heads of these households have dramatically reduced their (the victims’) families’ incomes for food, clothing, shelter, and health. They also claim that this has left the children at a greater “risk of child labour and exploitation”.

While it is often the case that statistics for something which is illegal – such as child labour in the Philippines – is hard to come by, the United States (US) Department of Labor managed to provide findings on child labour in the Southeast Asian country in 2018.

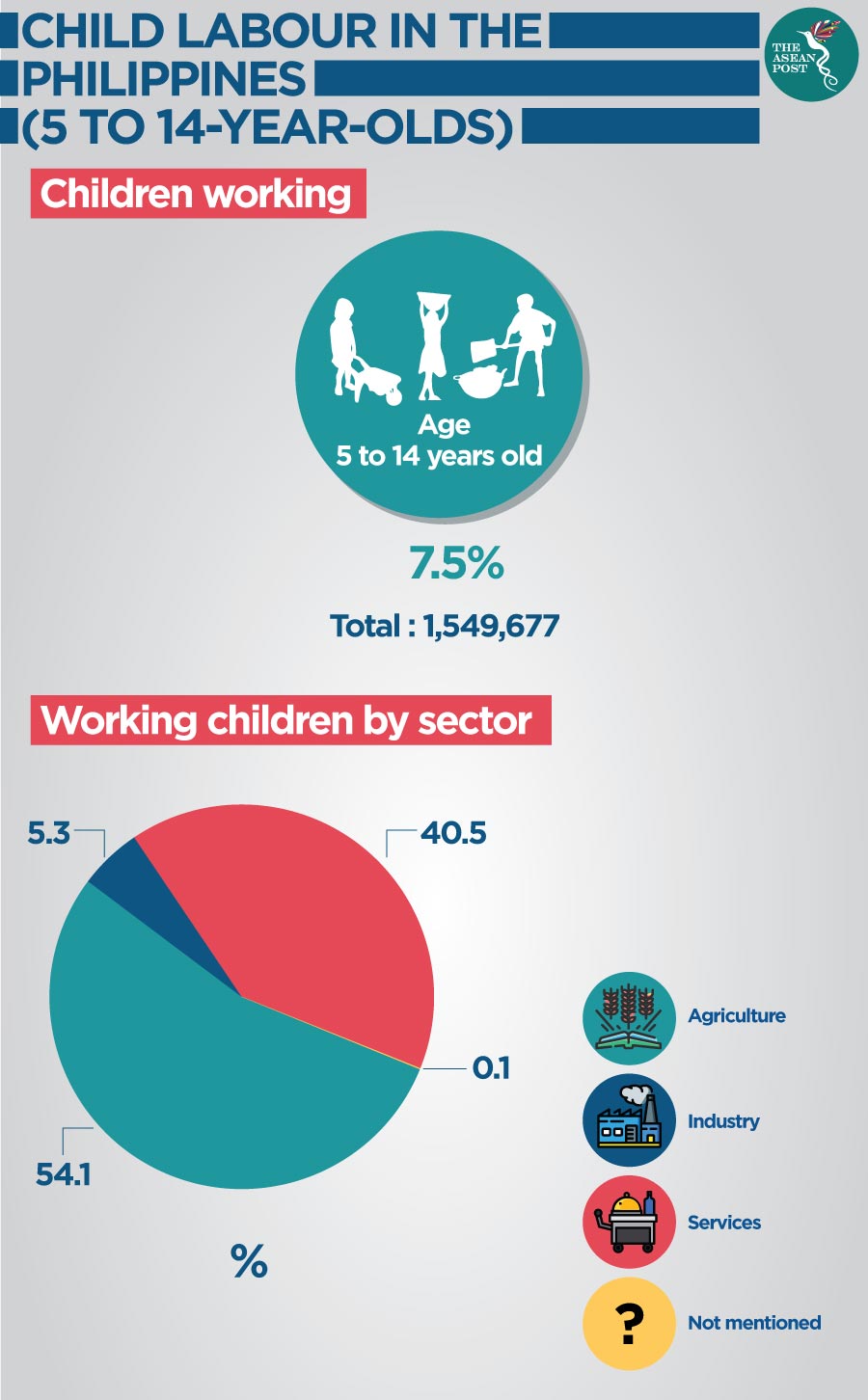

Based on the findings, percentage-wise the prevalence of child labour may seem low, but then when looking at actual numbers, one quickly realizes that the country does have an issue as far as child labour goes. The findings state that only 7.5 percent of Filipinos aged five to 14 were found working in 2018, nevertheless, in a total population of more than 100 million, this 7.5 percent also equates to 1,549,677 children.

But there’s also another, even darker side to the story.

According to a recent press release by the Australian Federal Police (AFP), five alleged victims of online child sexual abuse and four "at-risk" children had been rescued in the Philippines following a referral from the Australian Federal Police. The teenage girls aged between 14 to 17 were saved by local police on the first day of a two-day operation in the island province of Biliran.

A 10-month-old, an 11-month-old and a couple of two-year-old children deemed "at-risk" by the police were also removed from one home, while a two-year-old child and an 11-month-old infant were removed from another home on Wednesday. On Thursday, four more alleged victims were located by police.

Earlier, in July, Sam Inocencio from the International Justice Mission (IJM) in the Philippines was quoted by a regional news agency as saying that it was “profitable and easy” for Philippine adults to meet the demands of child cybersex trafficking by turning a closet or corner of their home into a “cybersex den.”

Betrayed by loved ones

Based on IJM’s data, 50 percent of the victims in the Philippines are 12 years old or younger and most of them were abused by perpetrators who are known to them. Half of the abusers are people the victims love and trust most – their own parents. 70 percent of facilitators are related to or live near to their victims

According to IJM, trust is a key element that enables sexual abuse of children, especially when minors are very young and completely dependent on their guardian. Unlike in commercial sex trafficking, cybersex abusers in the Philippines tend to recruit children through existing relationships. Besides parents, perpetrators can also be the victims’ siblings, other relatives, friends or neighbours.

Another important point raised by Inocencio was that “this is a crime of financial opportunity rather than one that is criminally motivated.”

The study conducted by Pangilinan, Fernandez and Quijano, also found that as a result of the Philippine drug war, women are now faced with the responsibility of having to become breadwinners apart from handling their normal domestic chores. With few skills, limited education, and low job prospects, many widows are forced to find new husbands to ensure a steady source of income for their families.

The researchers also noted that some of the children ended up being left with grandparents because they were not welcome in the new households.

In the July report, it was noted that one of the victims of child cybersex trafficking – known only as 11-year-old Sasha – said that it was poverty that led her to become a victim.

“We didn’t have much to eat. My parents couldn’t provide for my education. Our house was tiny because we were poor,” she was quoted as saying. Sasha was abused by her own aunt.

While no direct links have been made between the effects of the “War on Drugs” and the prevalence of child sex trafficking in the Philippines, it is easy to see how such a link could exist. If this is the case, then the price of the “War” may end up becoming one that is too dear to pay. It is hoped, for the children’s sake, that the Philippine government would take this possibility into consideration.

Related articles: