Ministries and child protection non-governmental organisations (NGOs) in Cambodia recently established a joint-committee for the implementation of the Action Plan to Prevent and Respond to Violence Against Children.

According to Touch Channy, a Ministry of Social Affairs, Veterans and Youth Rehabilitation spokesperson, the committee is headed by its minister, Vong Soth, and comprises 22 members – 15 from various ministries and institutions and seven from NGOs.

While Cambodia has certainly been improving its game as far as taking care of its children goes (the joint-committee being just another example of this), there is still room for more improvement as violence against children continue.

When speaking of violence against children in Cambodia, a study often cited is one conducted in 2013 by the Ministry of Women’s Affairs, the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) Cambodia, and the US Centers for Disease, Control and Prevention. According to the Cambodia’s Violence Against Children Survey 2013, more than 75 percent of children experience violence (physical, emotional or sexual) before the age of 18. 50 percent experience physical violence, 25 percent emotional violence, and five percent sexual violence.

However, it has also been revealed according to more recent 2017 data from the World Tourism Organization (UNWTO), that each year three million people take a trip in order to have sexual relations with minors. The most popular destinations are Brazil, the Dominican Republic, Colombia, Thailand and Cambodia.

Numerous reports have also noted that, as Cambodia becomes more internet-savvy, new issues with regards to violence against children have cropped up. These issues include sexual abuse of children as well as cyberbullying.

The fact that the Action Plan to Prevent and Respond to Violence Against Children even exists and was introduced in 2017 goes to show how long the problem has persisted. The fact that a joint-committee has just recently been established serves to highlight the currency of the problem.

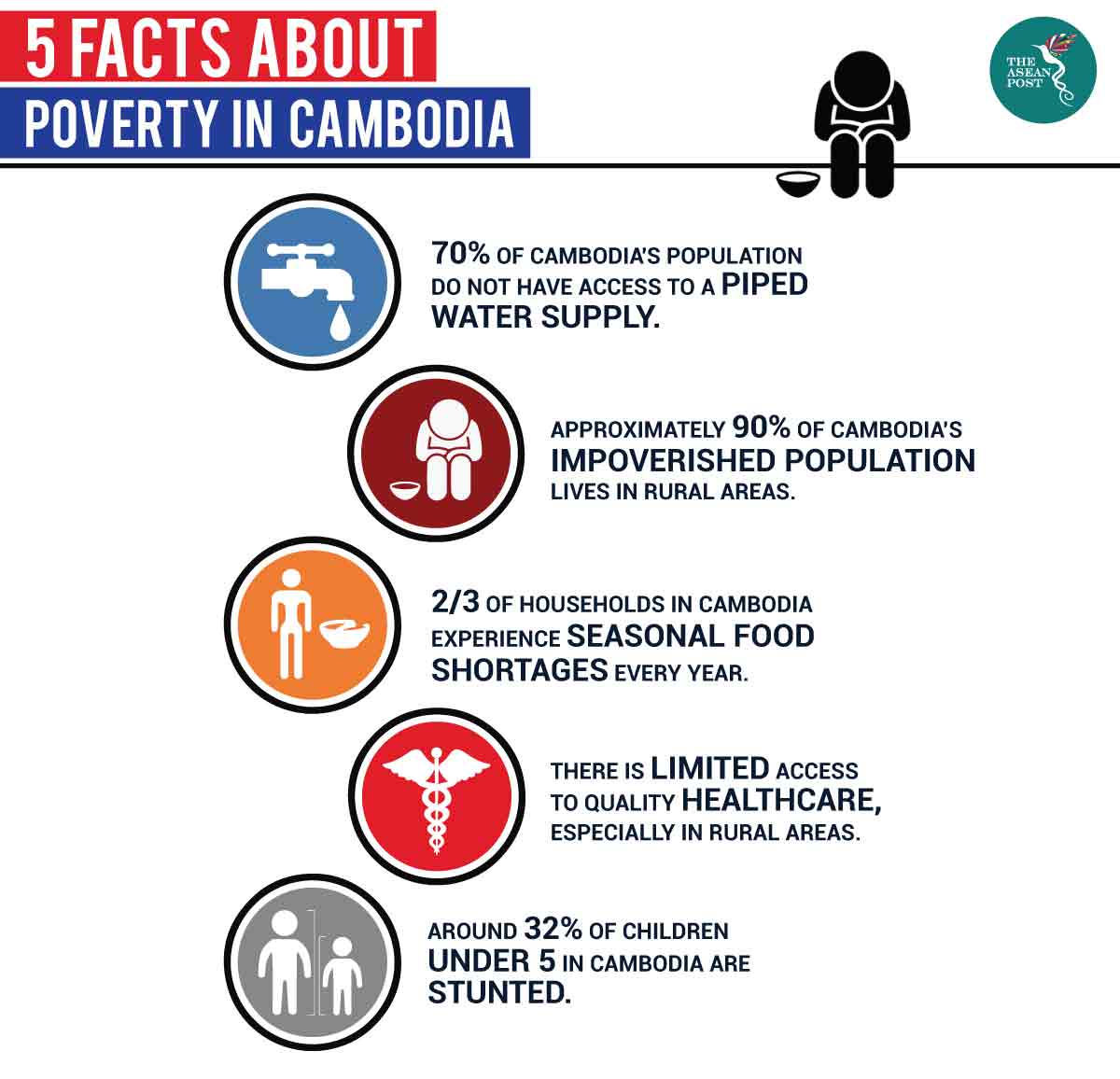

In tackling the issue, perhaps one area the Cambodian government should also look at is poverty.

Between poverty and violence

It is no surprise that poverty and child abuse go hand in hand. According to National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) research associates Christina Paxson and Jane Waldfogel in Work, Welfare, and Child Maltreatment; children with two non-working parents or parents whose income is below 75 percent of the official poverty level are more likely to be subject to neglect and abuse.

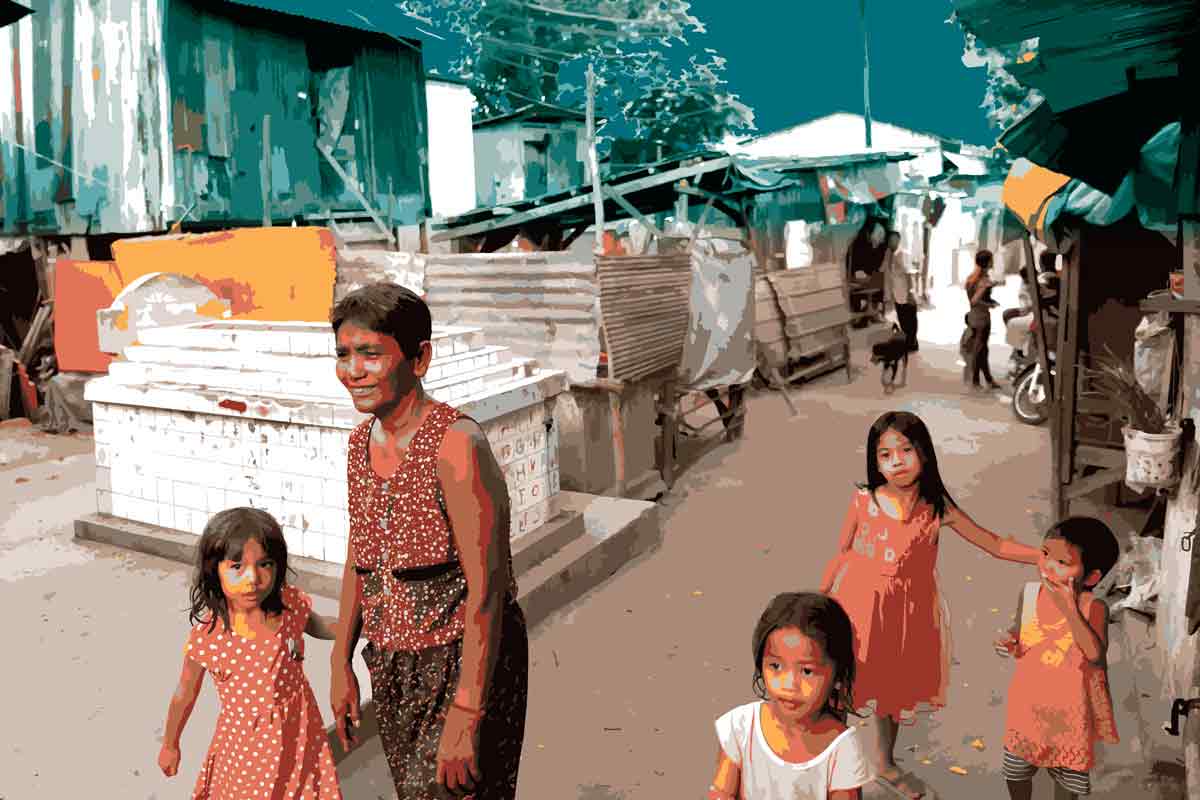

In May last year, UNICEF Cambodia interviewed mother of three, Sen Nary who sells seeds to bird-feeding tourists and, along with her tuk-tuk driving husband, work seven days a week, from dawn until dusk. Nary admitted that in the past, their hardship sometimes overwhelmed them and caused them to be violent towards their children.

“I used to scold and hit my children when I was angry. I pinched their ears. Every day I felt heavy like a stone was inside my body. I asked (myself) why my children were so disobedient and why they could not be like other children. And then I felt hurt and wanted to hit my children,” she was quoted as saying.

Nary has since turned her life and her children’s lives around through positive parenting but this is not the only instance where poverty causes violence towards children. News reports have also highlighted Cambodian mothers who have sold their daughters into sex slavery. According to a 2018 report titled “Blood Bricks” by researchers at Royal Holloway, part of the University of London, kiln operators generally consolidate the debts of struggling farmers, who move on site with their families to work long hours in dangerous conditions, and are paid by the brick.

“When the borrowers die or become unfit for work, their debt is forced upon their children, some of whom never leave,” the report said.

In September last year, the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and the Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative (OPHI) released its 2018 global Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI). While poverty has been dropping in the country, the report found that 35 percent of Cambodians are still living in poverty.

The Cambodian government is obviously serious about taking better care of its greatest asset – its children. Current efforts deserve to be applauded, but if the government is truly serious about taking care of its children’s rights then, perhaps the economy is another area it should keep a close eye on.

Related articles: