Digital technology and Southeast Asia’s high internet penetration have transformed the region’s music industry. The global music landscape has enabled consumers to discover a wide range of genres, sound and artists via music streaming apps such as Spotify, Apple Music and SoundCloud. Spotify is now the global leader in music streaming with a worldwide community of over 159 million users as of 2018.

The global revenue from music streaming in 2017 grew to 41.1 percent of the music industry’s total income of US$17.3 billion, based on data from the International Federation of the Phonographic Industry (IFPI).

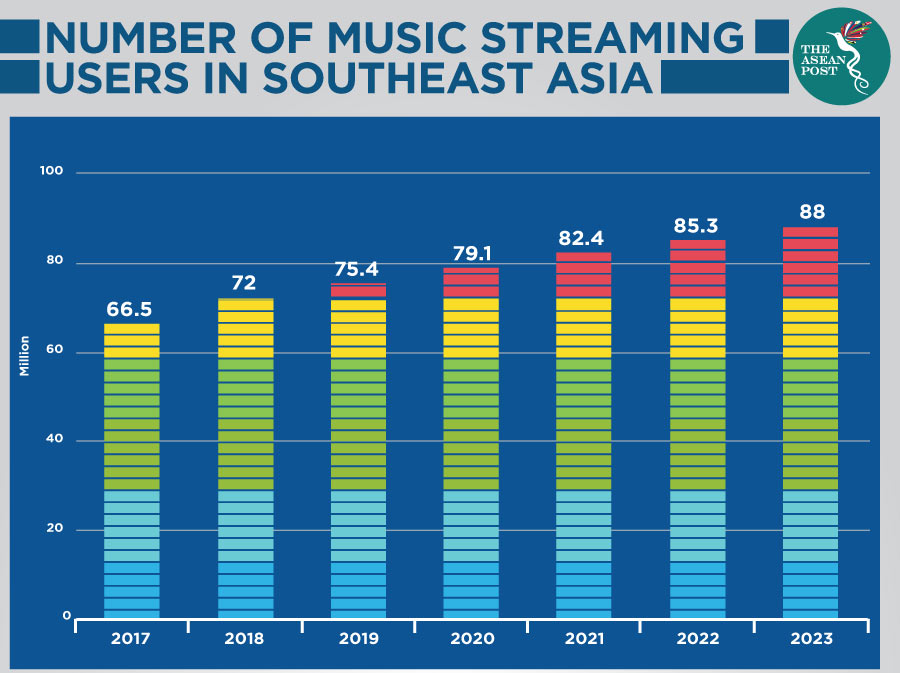

A 2019 Statista report, revealed that music streaming revenue to date in Southeast Asia amounted to US$254 million in 2019 and is projected to grow to US$293 million by 2023. The report also revealed that user penetration across the region is 11.4 percent where 38 percent are between the ages of 25-34 years.

Streaming music appeals to users as it allows them to store thousands of songs offline on multiple devices, making purchasing music downloads unnecessary.

Analogue is back

Despite the allure of digital media, vinyl records stand to be one of the fastest-selling and growing mediums for music. And surprisingly, the re-emergence of analogue formats such as cassettes and vinyl are happening in parallel to digital streaming. According to the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA), global vinyl record sales in 2015 was valued at US$416 million and is projected to reach US$500 million this year.

In Southeast Asia, the cassette revival is an underground fixture. There are no vinyl-pressing plants here, but cassette plants still dot the region. In Malaysia, the cassette has become an inexpensive format for fledgling artists to get their music heard. The manufacturing cost for cassettes can be as low as RM4 (US$1) per tape, compared to RM60-80 (US$14-19) for a single vinyl record. The high cost of vinyl is also a barrier for many young bands and DIY labels in Indonesia, Thailand and the Philippines.

Teenage Head Records, a Malaysia-based indie record store has been producing cassette tapes since 2014.

“Cassette culture isn’t going away anytime soon. The tape revival, which started kicking-in in Malaysia two years ago, has been a good thing. New bands have something to put out. Tapes are also not as expensive as records. You can now release something that is affordable and also very artsy,” Radzi, owner of Teenage Head Records, told Malaysian media.

Harmful to the environment

Vinyl is short for polyvinyl chloride (PVC), and its production process is not particularly eco-friendly as it involves toxic acids and consumes a lot of energy. Andie Stephens, associate director of Carbon Trust, a corporate carbon footprint measuring company, said that vinyl’s environmental impact includes energy used in the extraction of crude oil from the ground and the subsequent processing and manufacturing.

Recycling of PVC is also an issue, as it takes at least 100 years for it to decompose. A 2019 article, ‘The environmental impact of music’, by Sharon George and Dierdre McKay from Keele University, revealed that the sales of 4.1 million records would produce 1.9 thousand tonnes of carbon dioxide (CO2).

Misconception

The idea that streaming is a zero-carbon medium for listening to music is a misconception. All streaming services depend on a network of energy-intensive server farms consisting of computers. Music is not stored on personal computers or smartphones and is instead, stored on servers within huge data centres.

“An expected by-product of digital growth has always been a decrease in the perceived heavy environmental cost associated with physical products,” writes Dagfinn Bach, author of ‘The dark side of the tune: the hidden energy cost of digital music consumption,’ which was published in 2012.

Data centres generate an immense carbon footprint. These warehouses run 24 hours a day every day, producing heat that needs to be continuously cooled. This entails a massive amount of electricity, which in most cases relies on fossil fuels for its generation.

Even though vinyl has a higher upfront cost of production, it may have a lower footprint over time. According to Sean Fleming’s ‘Streaming music isn’t as green as you might think,’ article featured by the World Economic Forum (WEF), the carbon footprint of a vinyl record remains the same no matter how many times it is played, requiring only enough electrical energy to spin the record and provide its amplification.

Meanwhile, streaming may reduce the upfront production but it makes increased energy demands and emissions every time a song is played. Bach wrote that streaming an album over the internet 27 times can use more energy than the manufacturing and production of its vinyl equivalent.

Unless data centres are run by sustainable means and produce a net-zero carbon footprint, streaming will always have an environmental cost. Perhaps analogue music formats might not be a bad option for now.

Related articles: