The recent signing of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) between ASEAN and five Asia-Pacific countries (China, Japan, Australia, South Korea and New Zealand) has created the world’s largest free-trade zone that covers about a third of the world’s population and accounts for about 30 percent of the world’s gross domestic product (GDP).

The European Union (EU) is not a signatory to RCEP, but is paying close attention to it. The ASEAN Post recently spoke to Igor Driesmans, the EU ambassador to ASEAN, to understand better the EU’s position on RCEP.

Ambassador Driesmans hails the agreement as a step forward in the direction of free trade and stressed that the importance of RCEP goes way beyond the economic benefits for its members.

First of all, it is a clear statement in favour of free, open and fair trade. In an environment where some countries are engaging in protectionism and trade wars, “it is important that so many countries affirm the importance of free and open trade and say they are against protectionism,” Driesmans said.

Secondly, RCEP is a strong sign that member countries are in favour of rules-based trade.

“In a time when the World Trade Organisation (WTO) is under attack and it is very difficult to agree on anything, having so many countries come together around a solid trade agreement and anchoring their cooperation to rules, is in itself an achievement,” he added.

Some commentators called the RCEP a political victory for China, but RCEP is, by all accounts, a major political success for ASEAN, said Driesmans.

While the need for a comprehensive regional agreement was accepted – states the Brookings Institution in a study on RCEP’s geopolitical significance – the region’s major economies were for different reasons not acceptable as the driving force for the deal. In 2012, ASEAN managed to broker a deal with more than 30 rounds of negotiations and eight years later, RCEP saw light.

Here, Driesmans says, lies the third reason why this agreement is so important. RCEP “strengthens ASEAN centrality. While some press reports defined it a ‘China-dominated agreement,’ it is important to remember that ASEAN was at the centre of it. The 10-countries negotiated as a bloc and there was, unlike many other instances, a single negotiator throughout the whole process,” he added. The ASEAN negotiator was Iman Pambagyo of Indonesia.

From a practical point, Driesmans said it is difficult to quantify the benefits for the EU, but “anything that does away with trade restrictions in the region is beneficial for European companies. We are still working through the 20 chapters of this massive document of more than 500 pages.”

As for the region, it will definitively benefit from the agreement. Countries like Malaysia, Indonesia, Vietnam, and Thailand that have seen an inflow of investments following the shift out of China of some multinationals in the wake of the pandemic and the United States (US)-China trade war. They are now likely to attract more investments form Japan, South Korea and Australia, “although we’ll have to wait a few years to see any effects,” he warned.

According to an analysis by the Peterson Institute for International Economics, the economic benefits of RCEP are enough to offset the consequences of the US-China trade war and add US$209 billion annually to world incomes and US$500 billion to world trade by 2030, with the bulk of the gains going to RCEP members.

A major step forward towards freer trade will be the harmonisation of the rules of origin, the criteria needed to determine the national source of a product. There is wide variation in the practice of governments with regard to the rules of origin, so the fact that RCEP sets a legal framework to harmonise them is “an important step forward, although it will be a few more years before we have a clear agreement,” said Driesmans.

Driesmans also stressed the EU’s commitment to ASEAN and its continued engagement with the region as a whole. The EU is the main Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) source into ASEAN and one of its main trading partners, with imports worth €125.1 billion (US$149.79 billion) and exports to the region reaching €85.5 billion (US$102.38 billion) in 2019.

However, he does not see the EU joining RCEP any time soon. While article 20 of RCEP leaves the or open to third parties to join, this is not an EU priority.

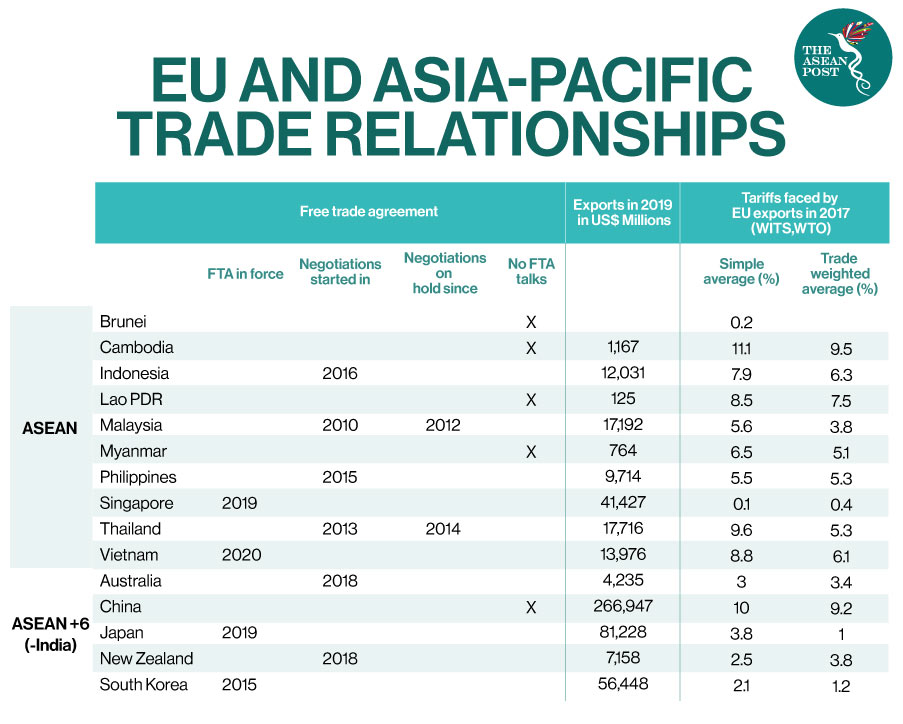

“The EU focus is on accelerating the conclusion of bilateral free trade agreements (FTAs) with ASEAN nations,” Driesmans said. The EU has in place free trade agreements with four RCEP members (Singapore, Vietnam, Japan and South Korea) and negotiations are underway with several others (Indonesia, Thailand, New Zealand and Australia) and that’s where the EU is concentrating its efforts.

The FTA with Indonesia is the next one likely to be finalised. Indonesian President Joko Widodo hoped to reach an agreement by the end of 2020, but then the coronavirus pandemic put things on hold. Pressed for a target date, Driesmans added that if “negotiations proceed smoothly, everybody puts in goodwill and makes the necessary concessions, end of 2021 is a realistic possibility.”

Related Articles: