Myanmar is gearing up for elections this year. The general election, tentatively scheduled for some time in November, will essentially pit Myanmar State Counsellor Aung San Suu Kyi’s National League for Democracy (NLD) against the military-aligned Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP), the country’s two major political parties.

As the country inches closer to D-Day, one thing political analysts and observers will be keeping a close watch on is social media – especially popular platform, Facebook.

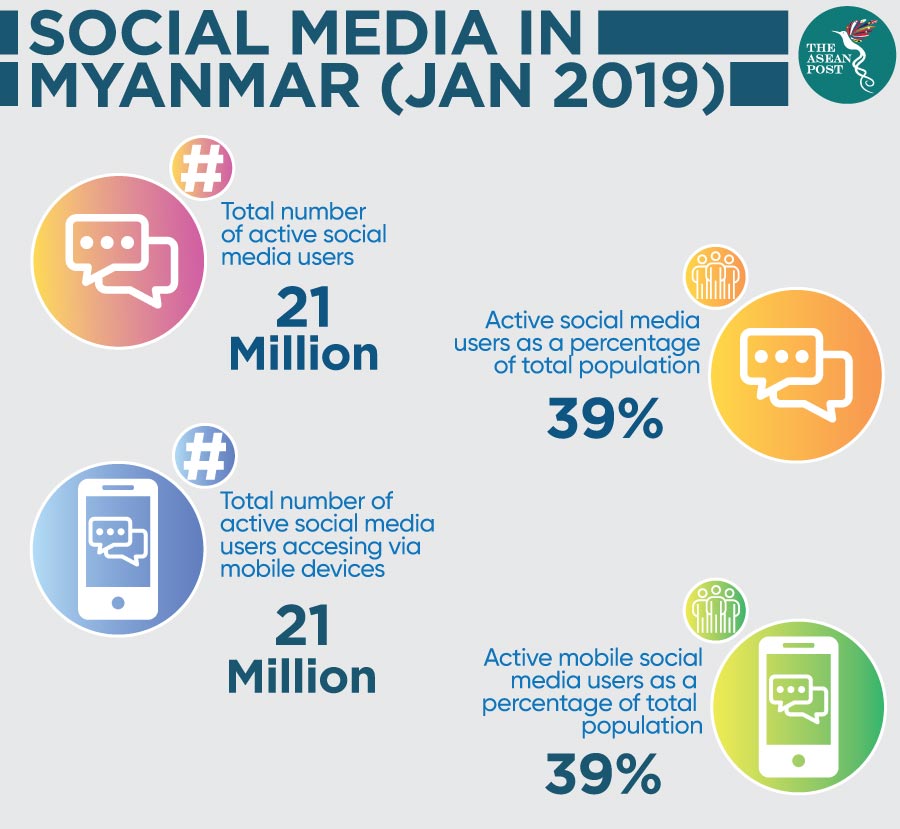

According to statistics from global social media agency, We Are Social, Myanmar doesn’t do too shabbily when it comes to social media penetration in the country. While there is certainly room to grow, the numbers are already significant.

As of January 2019, Myanmar had 21 million active social media users – a 39 percent penetration rate for its 54.1 million population. This is an increase of three million (17 percent) compared to the same period in 2018. Of that number, Facebook has an audience of 21 million, coming in first place for social media platforms in Myanmar. In comparison, Instagram was second with an audience of just 810,000.

We Are Social also noted that Facebook is the third most visited website by Myanmar netizens after Google and YouTube which came in first and second, respectively.

While Facebook is the most used social media platform in Myanmar, the largest demographic on Facebook are those in the 18 to 24 years age group (44 percent). Users aged 25 to 34 (37 percent) came in second.

Facebook forms team

Facebook is big in Myanmar. In fact, local media recently quoted a spokesperson for the US-based social media and technology company as saying that Facebook had formed a team to monitor the use of its platform in Myanmar, in lieu of the upcoming 2020 general elections.

“We also know that we must protect people from those who attempt to spread hate and misinformation. That’s why we’re committed to keeping the platform safe not only during Myanmar’s 2020 election, but all year-round,” the spokesperson told local media in Myanmar.

It was also reported that some legislators had expressed concerns about the use of social media to spread hate speech and fake news. Sai Ngaung Sai Hein, a Pyithu Hluttaw (Lower House) representative for Kyaukme Township in Shan State, urged the Union Election Commission - the national level electoral commission of Myanmar, responsible for organising and overseeing elections - to prepare for problems that could arise from social media political campaigns.

“The 2020 election is fast approaching. Many said it will be a fight on Facebook,” he was quoted as saying.

It is expected that Facebook will be paying extra attention to Myanmar during this election period especially considering the controversy it ran into in 2017 when the company failed to take timely action when its platform was used by Buddhist extremists to inflame hatred and violence against the Rohingya minority. Even as the Myanmar military, known as the Tatmadaw, was carrying out a campaign of ethnic cleansing against the Rohingya, Facebook designated a Rohingya insurgent group, the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army, as a dangerous organisation while taking no action against the Tatmadaw.

A Facebook post calling for violence against the Rohingya was shared over 13,000 times and had over 2,000 comments. This was just one of many examples of hate speech being shared on Facebook at the time. In April 2018, a group of six Myanmar civil society organisations posted an open letter to Mark Zuckerberg, criticising the inadequate response by Facebook on reports of hate speech on the platform.

It was not until August 2018 – a year after 25,000 Rohingya were killed by the Tatmadaw and allied Buddhist militias, and 700,000 Rohingya were forced to flee the country – that Facebook took action and banned Tatmadaw leaders from its platform. Facing growing public pressure, the company also commissioned and published an independent Human Rights Impact Assessment on the role its services were playing in the country. Facebook also committed to hiring 100 Burmese native speakers as content moderators.

Facebook’s decision to form a team specifically to monitor the use of its platform in Myanmar certainly looks like a pre-emptive measure to ensure that nothing ugly goes down on social media during this sensitive period in time for the country. The hope is that this will help ensure content on Facebook stays balanced while continuing to provide a platform for proper freedom of expression that is exercised ethically.

Related articles: