Urban farming could help provide a boost to the region’s food security and safety issues. The traditional farming system, though productive, has serious downsides which include food wastage, polluted ecosystems and significant greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions.

According to the United Nation’s (UN) Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) and NASA, an additional 109 million hectares of new land will be needed to feed the world’s population by 2050. Presently, over 80 percent of arable lands suitable for crops are already in use. The total land used for agriculture in ASEAN currently stands at 30 percent, or 132,953 million hectares.

The current quality of land used for agriculture is being threatened by degradation due to over exploitation, pollution and the shortage of available water. Feeding an estimated 10 billion people in 2050 without further destroying the environment is a tall order indeed.

A Tall Order

Rapid urbanisation is causing an increase in urban poverty and urban food insecurity. Bringing food production into cities could be a responsible solution towards maintaining a sustainable system.

Urban farms focus more on providing city dwellers with food security and economic diversification. Governments could encourage the use of underutilised land for constructing small farm gardens for communities in the immediate area while increasing environmental awareness among them.

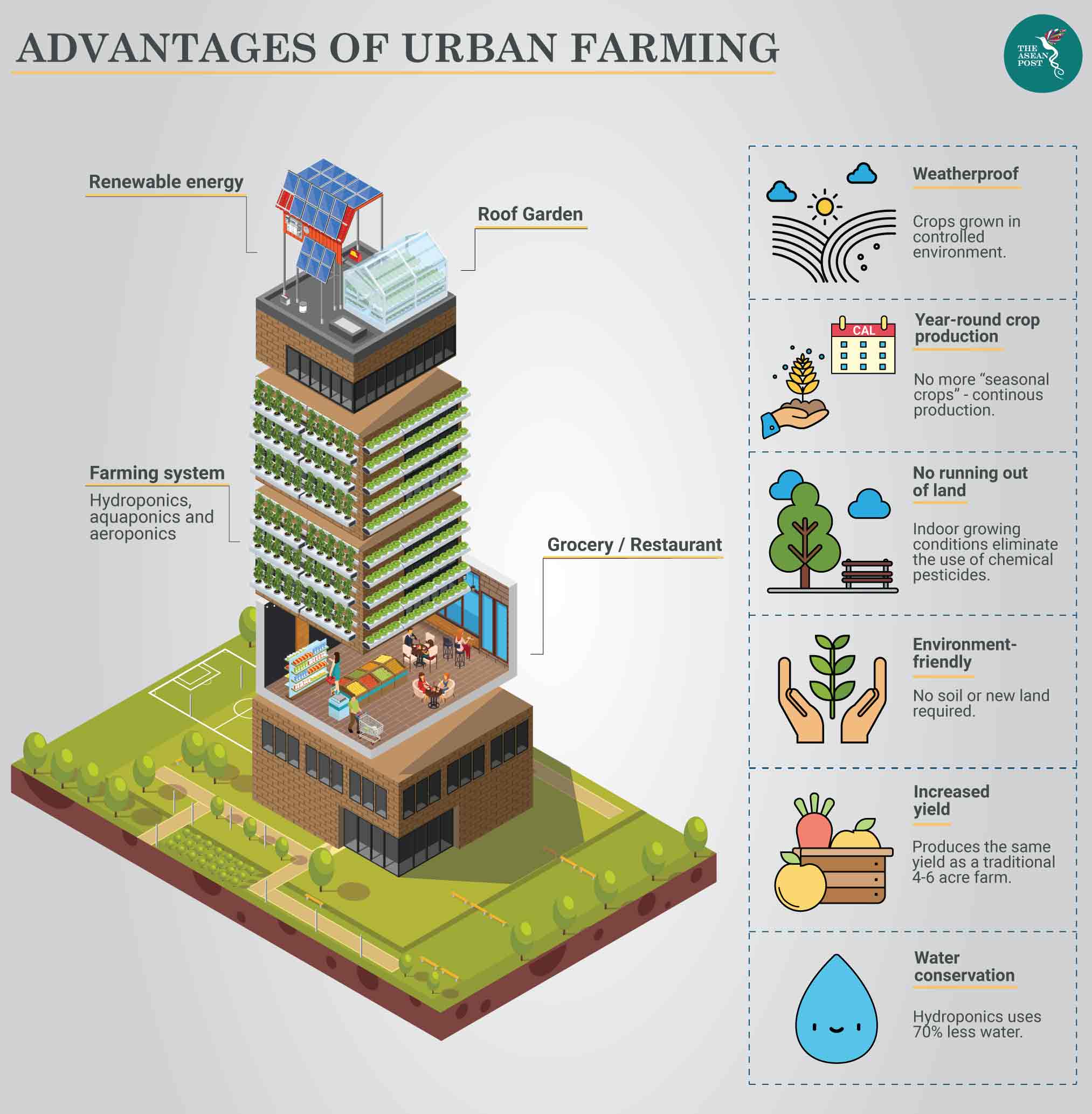

Another non-traditional farming method which takes advantage of urban spaces, especially tall buildings, is vertical farming. Usually found on rooftops or in abandoned buildings, vertical farming has a highly controlled environment with temperature, humidity, light and water levels being closely monitored at all times. It significantly reduces the need for toxic and costly pesticides.

According to the Association for Vertical Farming, by utilising aeroponics or aquaponics, a vertical farming system requires 70-95 percent less fresh water than traditional farming. It also uses less space when the rooftops of offices or supermarkets are utilised.

Traditional farming runs the risk of unpredictable weather which accounts for 50 percent of failed crops during harvest. Vertical farms on the other hand can have a yield of at least 90 percent every harvest. Experts estimate that a 30-story farm could feed 50,000 people for an entire year.

Traditional agriculture accounts for 15 percent of global GHG emissions from machinery and transportation. Because vertical farms are based in urban centres, the distance required for travel is far shorter.

A resilient, local economy can survive catastrophes that would otherwise doom a supply chain-independent system. Dickson D. Despommier, professor of Public Health in Environmental Health Science at Columbia University and author of the book, ‘The Vertical Farm: Feeding the World in the 21st Century.’ says that “the world would be a much better place if we had vertical farming.”

Sky High

Singapore is currently the front runner for vertical farming. Companies like Sky Greens and Comcrops are showing the ASEAN region the effectiveness of the system which has increased the island nation’s food production. There were more than 30 vertical farms in Singapore in 2018.

Singapore produces only 10 percent of its food, importing the rest due to the unavailability of land. With current issues of climate change, a growing population and pressing food security issues, Singapore does not want to depend on imports to feed its 5.6 million people. The government there has called for farmers to answer the call to “grow more with less,” with the hope of raising food production to 30 percent by 2030.

Sky Greens claims to be the first economically viable vertical farm in the world. Jack Ng, entrepreneur for Sky Greens says his products range from Chinese cabbages, bak choi, kai lan, and lettuce, to other leafy green vegetables. The company also guarantees freshness as produce hits the shelves a mere three hours after harvesting.

Although Sky Greens’ vegetables cost slightly more than those from traditional farms, the proximity to consumers reduces transportation costs as well as cuts down on storage and spoiling during transport. Sky Greens was able to get a positive return on investment after just five years in operation.

Comcrop’s Allan Lim believes high-tech urban farms are the way forward for cities. The company builds its farms on shopping mall roofs along Singapore’s Orchard Road, and uses vertical racks and hydroponics to grow leafy greens and herbs.

Regional Initiative

Urban farming in Southeast Asia is still limited and scattered. Though it is not without its following.

The Philippines has new laws under the Urban Agriculture Act of 2013 which mandates the Department of Agriculture to promote the use of urban agriculture and vertical farming. Aimed to ensure food security and rejuvenate the ecosystem, these laws also mandate that abandoned government lots and buildings owned by national or local governments should be considered for growing crops.

In Malaysia there are movements such as CityFarm Malaysia which is an organisation whose objective is to inspire city farmers with the ability to grow locally for sustainable food production. Currently, Bangkok is developing rooftop farms and mixed-use skyscrapers with open-air farms.

Despommier has said cost continues to be the major drawback as “it requires a heavy investment and creativity to invent the methods and to create a social buy-in.” Vertical urban farming should not be seen as just a current trend but as a viable alternative to food production. Nor should it be seen as a threat to traditional farming.

Can vertical farming solve the global food security problem? The UN’s FAO certainly thinks so, and wants the trend to prosper and become sustainably embedded within public policy.

Related Articles: