With a growing middle class and high internet penetration rates, fintech firms are mushrooming all over the country. In 2016, there were only around 50 firms operating in Indonesia and it is believed that there are now more than 150 fintech firms running in the country.

Many of the proponents for fintech are claiming that fintech will herald in a new era of banking, while sceptics are more cynical of the advantages that fintech could bring to consumers.

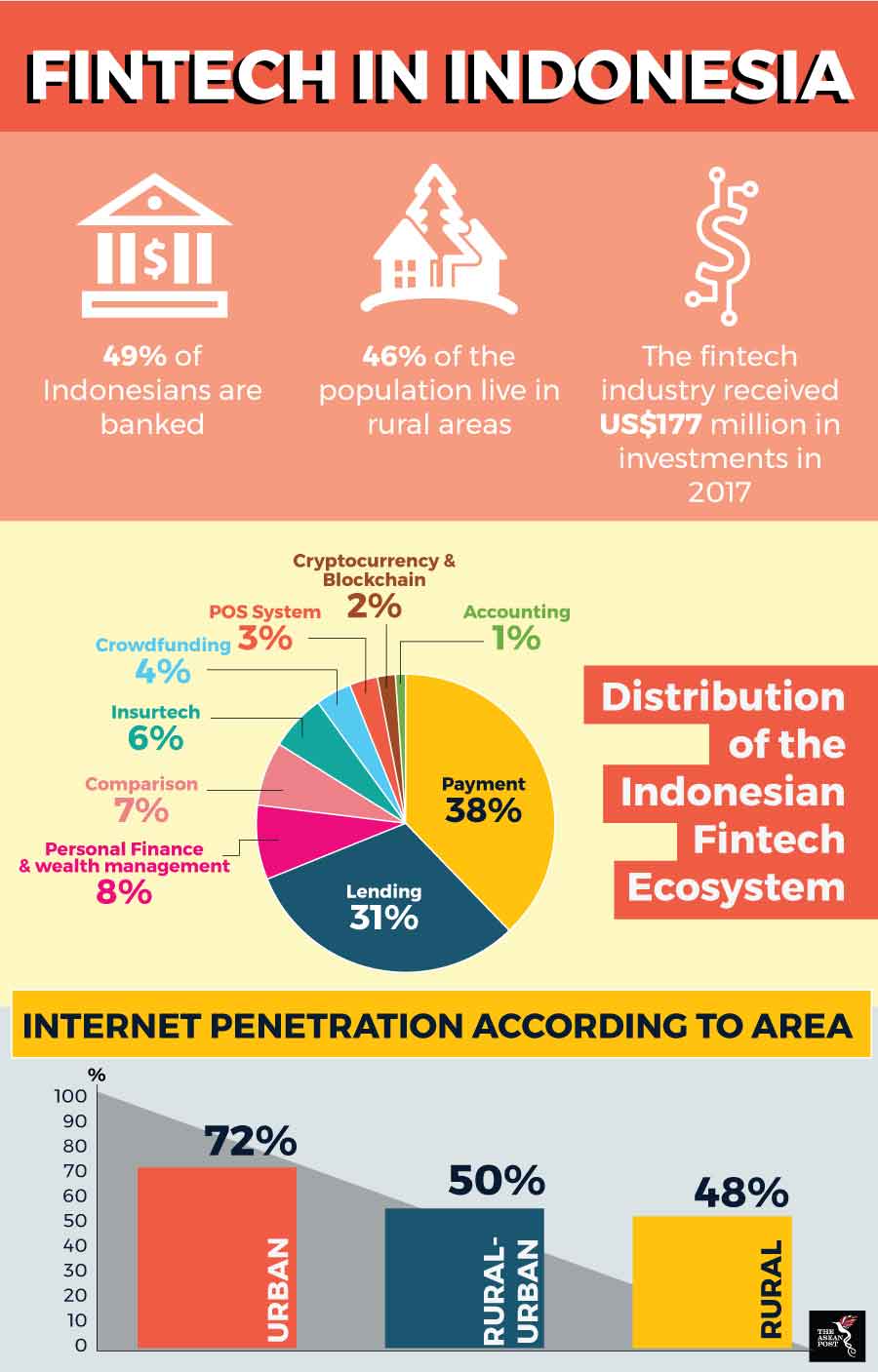

Large segments of the population in Southeast Asia, particularly Indonesia are unbanked – meaning that they do not have access to the services of a bank or a financial organisation. This is probably due to the fact that Indonesia is an archipelago made up of over 17,000 islands. Half of the population there live in rural areas, making financial services inaccessible.

Despite the large number of unbanked in Indonesia, the country’s internet penetration rates are on the rise. According to a survey by the Association for Internet Service Providers in Indonesia (APJII), internet penetration is 72 percent in urban areas, 49 percent in rural-urban areas and 48 percent in rural areas. With internet rates and smartphones becoming more affordable, many people in Indonesia today bank online as opposed to having a regular bank account. This also explains why virtual wallets such as GoPay and WePay are also on the rise in the country.

Fintech for the rural

Fintech firms are capitalising on this inequality between internet penetration and access to financial services which has led to the rapid growth of the fintech scene in Indonesia.

In February last year, Smartag International entered a joint venture agreement with Indonesian fintech firm PT Supratama Makmur Sejahtera (PTSMS) to form a new company which will see Smartag owning 51 percent equity while PTSMS will own 49 percent.

The company undertook the “Indonesian Project”, an initiative to provide e-wallet services to 10,000 rural boarding school students. Many of these schools are owned by Islamic microfinance institutions like Baitul Mal Tamwii (BMT). Smartag is looking to combine these different financial platforms into one fintech platform which will give students access to e-wallet and BMT microfinancing services. The aim is to make such services available to the student’s family members, which would help the local village gain access to features such as microfinancing for local businesses.

Other initiatives like Amartha for example, focuses on providing financial services to small businesses using a peer-to-peer business model in rural areas of Indonesia. The business model is deemed peer-to-peer because Amartha connects investors and lenders directly to the applicant. Amartha has also developed a system that measures the credit score of an individual through unbanked financial transactions in rural areas.

Data concerns

However, there is a price to pay for financial inclusion. In the case of Amartha and many other fintech firms, their model for calculating credit scores from unbanked transactions often includes collecting data about demographics, doing behavioural profiling and running psychometrics tests (which many argue are unreliable). This data is valuable, and in the wrong hands could easily cause all sorts of trouble. Furthermore, there are also privacy concerns too as consumers are usually unaware what fintech firms do with such data.

Huy Nguyen Trieu, an associate fellow at the Said Business School in Oxford University points out that unlike traditional banks that make money from interest and fees, fintech firms generate revenue through the monetisation of data. At the moment, banks are regulated enough that your data will not be sold but in the fintech space, such legal frameworks do not exist as yet.

While these firms might have the noble intention of providing financial inclusion to those without access, providing loans and e-wallet services could miss the forest for the trees. Providing microloans and microcredit might help certain members of rural communities but more often than not, development in rural communities require institutional change. There are also plenty of documented cases where microloans have plunged individuals into deeper financial difficulty because they are unable to repay them.

Financial inclusion is never a bad thing but execution is often key. Regulations need to be in place so that data collection and profit are not prioritised over the needs of rural communities.

This article was first published by The ASEAN Post on 3 September 2018 and has been updated to reflect the latest data.

Related articles: