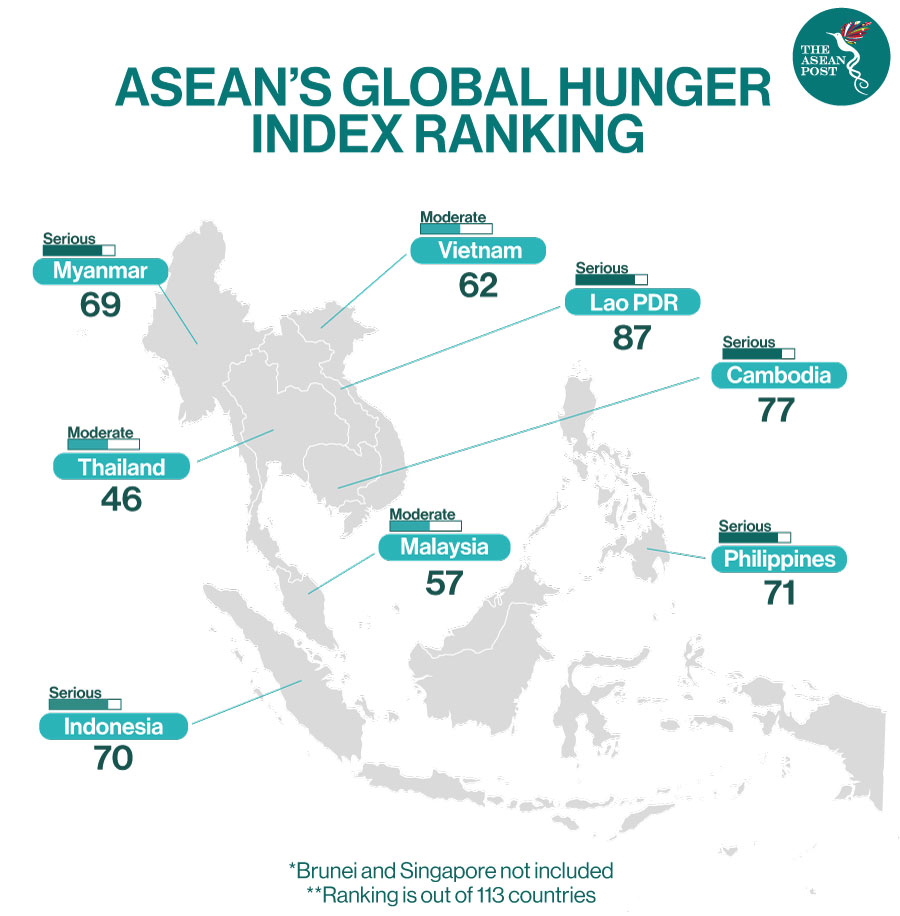

This past year COVID-19 has placed Southeast Asia on the brink of a socio-economic crisis, with 218 million informal workers’ livelihoods at risk and as many as 38 million people pushed into poverty. The crisis, coupled with typhoons that devastated countries such as Vietnam and the Philippines, risks rolling back a generation of progress in the fight against hunger. More than 64 million people in Southeast Asia were undernourished in 2019. Now, millions more face food insecurity.

As the new year begins, ASEAN member states have the opportunity to partner with community organizations such as food banks to provide much-needed hunger relief. Food banks – locally-led non-profits that have been on the frontline of the emerging hunger crisis – procure excess food and deliver it to food-insecure households, responding quickly to meet needs because they are embedded directly in their communities.

Food banks in Southeast Asia, in particular, have responded to the increased demand for food by mobilising resources from businesses and private citizens, providing a broad-based response to community needs, and rapidly adapting to logistical and market challenges. As the pandemic spread and forced government-ordered lockdowns, food banks helped fill the gaps left by school and business closures. When typhoons hit villages across Southeast Asia, food banks quickly organised emergency relief efforts for displaced families.

With increased support, food banks can help Southeast Asia prevent a deepening hunger crisis and build resilience at the community level. The work that the region’s food banks did in 2020 alone is telling.

The Food Bank Singapore, which delivered nearly 39 percent more meals in 2020 compared to 2019, developed an innovative program to deliver 50,000 meals to needy families while supporting hawker stands that are struggling to stay afloat after a drop in foot traffic. The program’s holistic approach involved donors that pay for meals, food and beverage partners that provide cooked meals at special rates, and volunteers that distribute the meals directly to low-income households.

In Malaysia, Kechara Soup Kitchen Society, which reached an additional 28,000 individuals since COVID-19, quickly expanded its services to include delivering emergency food kits and purchased foods directly to families in need. The food bank mainly reached the homeless and undocumented refugees in rural communities – people who were the most vulnerable during the health crisis.

Scholars of Sustenance in Thailand, which delivered an average of 2,500 meals per day, diversified its food distribution once the pandemic affected Thailand’s communities and economy. The organisation used to collect cooked food from restaurants and banquet halls. Since business and events slowed down tremendously amid the crisis, Scholars of Sustenance adjusted its operations to access a hybrid supply of prepared food and packaged products for the needy.

While agility and efficiency make local food banks unique, more collaboration and support will help them scale and meet the rising demand for food.

FoodCycle Indonesia, for example, partnered with food manufacturers unable to sell their stock. The collaboration and financial donations from corporate partners have enabled the food bank to produce emergency meal kits and distribute nearly 10 times as much food as it did in 2019.

In the Philippines, where the prevalence of moderate to severe food insecurity is more than 55 percent, Good Food Grocer ramped up its distribution by 500 percent and reached an additional 250,000 people. And when five typhoons hit the Philippines in just three weeks, Good Food Grocer quickly worked with the private sector to help families in Tiwi, Albay. More than 2,700 displaced families received a supply of personal hygiene products, fresh fruit, and non-perishable foods. The organisation also brought more than 1,000 food relief packs to people in the Bicol region.

Vietnam was another country impacted by natural disasters in 2020. The Vietnam Food Bank coordinated and helped establish 10 rural kitchen sites in and around the Ho Chi Minh City area to prepare meals for typhoon-impacted families. The organisation also organised food distribution in the Central Region of Vietnam in response to monsoonal floods and landslides. And when Vietnam’s Ministry of Health informed the food bank of a third wave of COVID-19 last December, Vietnam Food Bank prepared relief activities in Ho Chi Minh City in response.

It is clear that food recovery organisations are filling gaps in services that have been caused by the many external pressures faced by governments over the past year. The increase in the number of people turning to their local food bank is evidence of this need; however, with more resources, these organisations will be able to reach more people quickly and efficiently.

Governments and the private sector can provide the necessary increased financial and in-kind resources that food banks need. This would help these organisations ramp up services further while coping with a significant drop in food and monetary donations due to disruptions in local supply chains and rising unemployment.

As the full impact of last year’s challenges slowly becomes clear, ASEAN member states can address Southeast Asia’s emerging hunger crisis through close collaboration with aid organisations. And local food banks, working effectively with communities, businesses, and governments, are rising to the challenge.

Related Articles: