Thailand is famous for many things, one of which is its sandy beaches. But apart from being a huge draw for tourists from all over the world, the Land of Smiles’ over 3,000 kilometres of coastline and 8,000 islands also paint another picture, one that’s much more sinister.

The World Health Organization (WHO) was recently reported as saying that Thailand is still "number one" for deaths by drowning in ASEAN among children. In fact, the WHO says that the country’s death by drowning rate is twice as high as the world's average.

"In terms of numbers, we are number one in the ASEAN region; all agencies must work together to stop the deaths of these children," Thaksaphon Thamarangsi, director of the Department of Noncommunicable Diseases and Environmental Health with WHO's Southeast Asia Regional Office, was quoted as saying at an international conference recently.

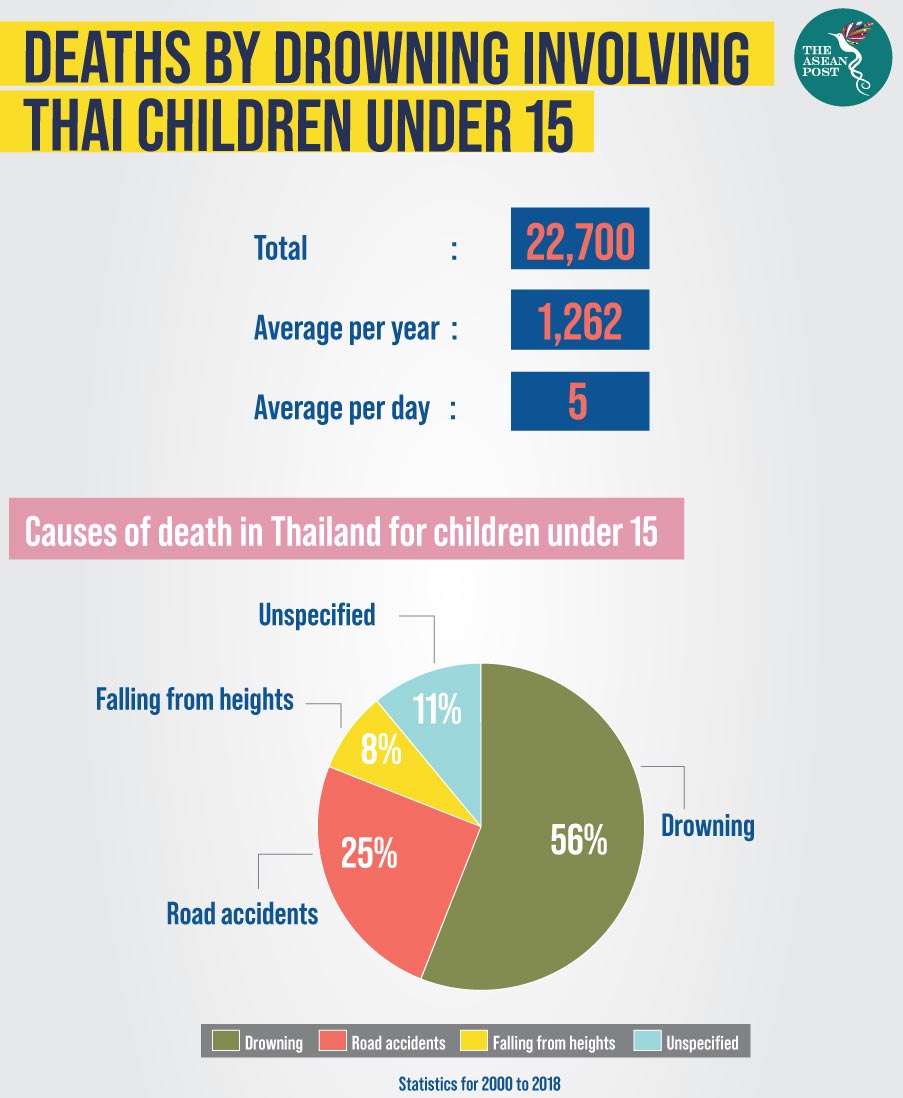

In a report released in March this year by the National Institute for Child and Family Development (NICFD), it was revealed that between the years 2000 to 2018, there were more than 22,700 drownings involving children under 15 in the kingdom, which averages about 1,262 children per year or a shocking five kids per day.

At the highest point, drowning caused about 56 percent of child deaths, followed by road accidents at 25 percent and falling from heights at eight percent. The number of drownings is reportedly highest during school summer breaks. The 12-day period from 12 to 23 April is the deadliest period for such accidents.

"Most drowning deaths occur in or near children's homes," said NICFD director Adisak Plitponkarnpim. "For small children, such incidents usually happen when parents leave their children out of sight. For older kids, they will sneak out to play in water with their friends without telling their parents, although they can't really swim.”

Government efforts

Adisak, however, acknowledged that the number of child drownings in Thailand has been decreasing over the past two decades due to improvements in swimming and water safety lessons. Last year, drowning only caused 727 child deaths, a significantly lower figure than the 1,244 deaths a decade ago.

In October 2014, Thailand’s Ministry of Public Health (MOPH) released a report entitled “Drowning Prevention in Thailand”. The report noted that the MOPH had established the Child Drowning Prevention Committee comprising officials from more than 30 public and private agencies to jointly set up policies, goals, and guidelines for the effort. The target was to reduce the drowning rate for children under 15 years to not exceed 770 deaths per 100,000 population by 2015.

Under the programme, the key policy directions include training all children aged six years and over to be able to swim for survival, designating the first Saturday of March each year as Child Drowning Prevention Campaign Day, having all health-care facilities educate parents who bring their children for immunisation and check-ups about drowning prevention, as well as train community leaders, teachers, parents, children and other people on drowning rescue including cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) among other things.

The fact that cases of drowning have steadily dropped goes to show that government efforts in decreasing the number of drowning incidents among children aged 15 and below are bearing some fruit. However, experts believe more can be done.

"Although the decline in the number of child drownings this summer is promising, drowning remains the leading cause of unintentional death for children aged one to four," Adisak was reported as saying.

To cut the high number of drownings, the NICFD director said all related agencies such as the Education Ministry and the Ministry of Public Health must keep promoting water safety awareness among children.

"We've done a great job over the last 20 years, but we can still do better. For example, many schools start teaching students to swim at the age of 10. That's a bit too late in my opinion. We should begin teaching them from the age of six," he said.

Adisak also revealed that the NICFD has set a target to reduce the number of child drownings in Thailand to less than 250 a year by 2022. Let’s hope Thailand is able to meet this new target as well.

Related articles: