Tigers once roamed wild and free across the jungles of the world. As apex predators, life was good. Fast forward to today and most of us already know that tigers around the globe are being threatened by an even deadlier predator – humans.

The case is no exception in Southeast Asia which has already seen the extinction of two subspecies: the Bali tiger (extinct since the 1930s) and the Javan tiger (extinct since the 1980s).

Almost all remaining subspecies of tigers such as the Indochinese and Malayan tiger are currently facing the very real possibility of extinction.

Just last month, Malaysia’s prime minister Muhyiddin Yassin cited a national survey and said that there are currently around 130 to 140 Malayan tigers left in the ASEAN member state – where the subspecies is mostly found.

Mark Rayan Darmaraj, World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF)-Malaysia’s Tiger Lead warned that if no immediate and drastic measures are taken to curb poaching, local extinction of the Malayan tiger would occur within three to four years.

Similarly, Indochinese tigers were once abundant in Cambodia, Lao, Myanmar, Vietnam, and Thailand. But due to human development such as road construction; which has fragmented habitats; as well as decades of poaching, their numbers have seen a sharp decline.

Today, people in Vietnam and Cambodia will no longer be able to spot Indochinese tigers as the subspecies has gone extinct in these two countries. Meanwhile, Lao and Myanmar are also seeing depressing numbers. According to a 2010 International Tiger Forum, Lao has a maximum of 23 tigers left while Myanmar has a maximum of 85. That was 10 years ago.

Nevertheless, according to a report in the Global Conservation and Ecology, the last tigers of Lao disappeared shortly after 2013 from Nam Et-Phou Louey National Protected Area. Experts believe it was most likely a surge in snaring that has caused such an event, despite large-scale investments in the park. With the loss of tigers in the kingdom’s largest protected area, the Indochinese tiger is most likely extinct in Lao, same as with the other two ASEAN member states mentioned earlier.

Threats

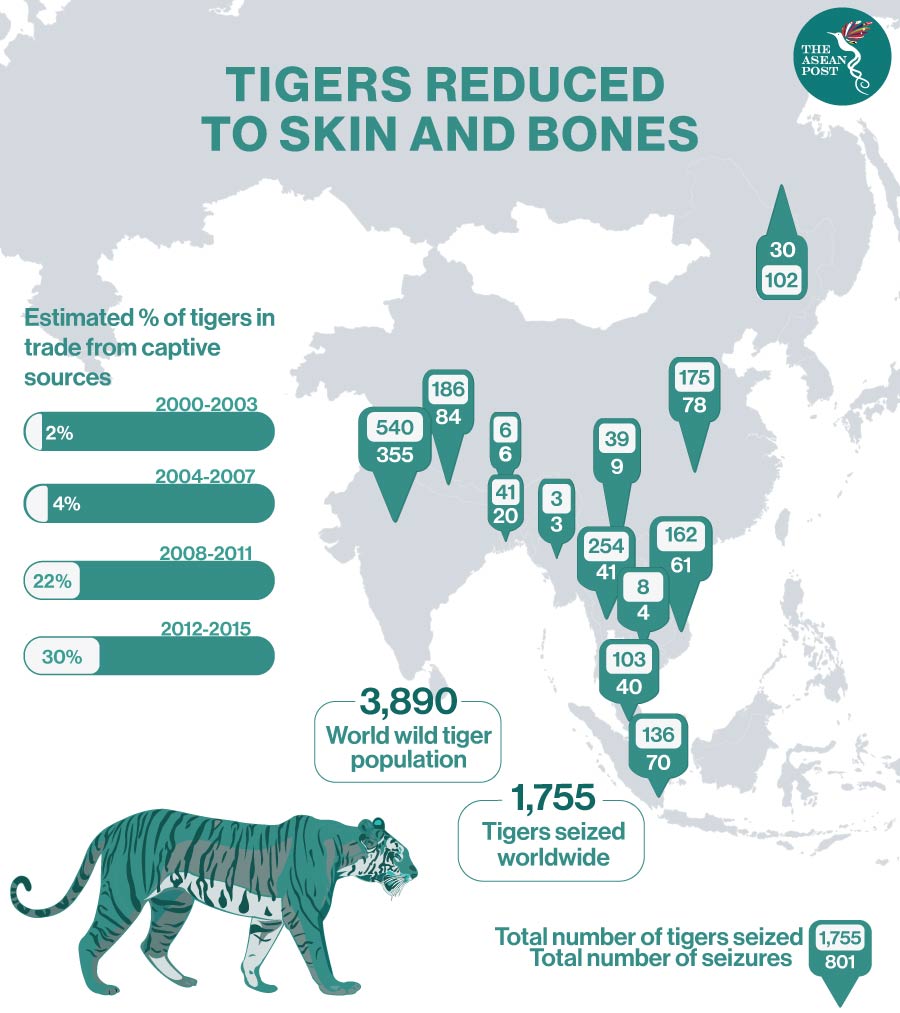

Between January 2000 and December 2015, it has been estimated that a minimum of 1,755 and a maximum of 2,011 tigers were killed based on the analysis of seized tigers, alive and dead, as well as tiger parts over the 16-year period. This estimation, provided in a report by TRAFFIC, a wildlife trade monitoring network, is based on 801 reported seizures across 13 Tiger Range Countries (TRCs). ASEAN countries account for more than half of the TRCs. The TRCs in the region are Indonesia, Lao PDR, Myanmar, Thailand, Vietnam, Cambodia and Malaysia. The other TRCs are Bangladesh, Bhutan, China, India, Nepal and Russia.

According to the report, during this period of time, on average, a minimum of 110 tigers were seized every year while 50 seizures were reported annually. The highest number of seizures were reported from 2008 to 2011 and the highest number of seizures was reported by India, accounting for 44 percent of all reported seizures. In 2016, the Cambodian tiger was declared “functionally extinct” with no breeding populations left in the wild.

According to the WWF, tiger numbers are in shocking decline across its range because of shrinking habitats, expanding human populations, poaching, and the illegal wildlife trade.

Vital tiger populations are also depleted by a growing commercial demand for wild meat in restaurants. Wild tigers are also poached in order to meet increasing demand for tiger body parts used in traditional medicines and new folk tonics.

The WWF also notes that while healthy habitats are extensive in some areas, they are under constant pressure from agricultural plantations, mining concessions and inundation from hydropower development. Habitat fragmentation due to rapid development – especially the building of road networks – is a serious problem. This fragmentation forces remaining tigers into scattered, small refuges, which isolates populations and also increases accessibility for poachers.

Hope For Wild Tigers

Today, it seems that the Indochinese tiger’s best hope comes from the Land of Smiles.

Thailand has set up a tiger conservation centre in the Huai Kha Khaeng Wildlife Sanctuary. There, local forest rangers will be trained to keep an eye on the critically endangered tigers as well as their prey animals like gaur and barking deer, which are being driven to extinction from hunting as well.

The director of Thailand’s Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) Anak Pattanavibool, who is also a tiger expert, currently puts the number of Indochinese tigers in Thailand at around 160.

“The western forest complex is our biggest hope,” he said. Listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, that forest is home to about 100 to 120 wild tigers, with 80 of these living in the Thungyai-Huai Kha Khaeng wildlife sanctuary.

Another glimmer of hope for the Malayan tiger sparked last month when camera traps set up early this year and recently retrieved by WWF-Malaysia revealed rare images of not just one – but four of the endangered subspecies. The set of images captured showed a female tiger and three cubs, which were identified as the same family.

“With less than 200 Malayan tigers left in the wild, this news comes as a timely message of hope for the species and for our continued tiger conservation efforts,” said Sophia Lim, CEO of WWF-Malaysia.

“It is heartening to know that our collective efforts are enabling a safer environment for our Malayan tigers to breed in their natural environment. It is a long road but this gives us some indication of hope,” added Mohamed Shah Redza Hussein, director of Malaysia’s Perak State Park Corporation (PSPC).

Related Articles: