A party-list group in the Philippines is pushing forward a bill that will grant 50 percent discounts from funeral services to poor families, as well as grant free funeral services for families in the country considered to be extremely poor. The bill comes following the revelation that dying in the Philippines is simply too expensive.

Bayan Muna representative, Carlos Isagani Zarate, citing a survey done on funeral services by the University of the Philippines (UP) School of Urban and Regional Planning in 2005, said the average funeral service package was PHP25,000 (US$493.56), while memorial lots in public and private cemeteries cost an average of PHP50,000 (US$987.12) for a lot package including succeeding lease payments.

“This is because most Filipinos already live lives of utter poverty and still die poor and indebted till the end. Funeral services generally are expensive, a stark and difficult reality confronting the large majority of impoverished Filipinos. Decent funeral services include the transport of the corpse, provision of casket, embalming, interment and conduct to the church and/or to the cemetery,” he was quoted as saying.

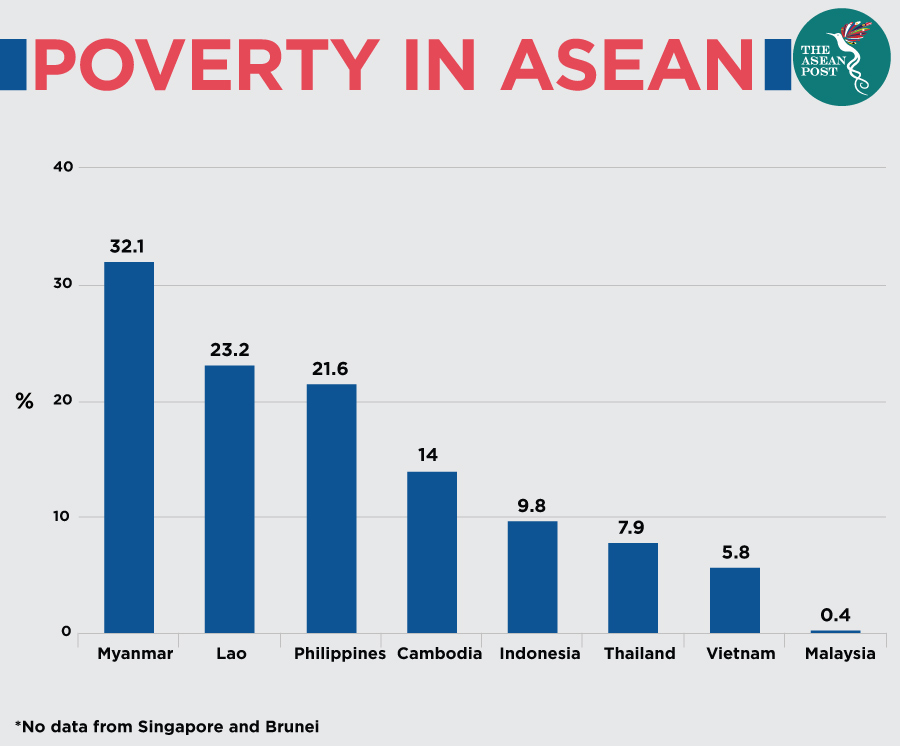

The Philippines official poverty rate dropped to 21 percent in the first half of last year from 27.6 percent in the first half of 2015.

Nevertheless, the Philippines continues to have one of the higher poverty rates in ASEAN.

Dangerous poverty

The bill comes at a crucial time as it deals with problems facing the poor after they die. Human rights observers would note that this matter is especially pertinent today in the Philippines.

Earlier this year, Amnesty International released a report in which it accused Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte’s War on Drugs as being nothing more than a “large-scale murdering enterprise”. More importantly, it claimed that the poor were often the ones being targeted.

“It is time for the United Nations, starting with its Human Rights Council, to act decisively to hold President Duterte and his government accountable,” said Nicholas Bequelin, Amnesty International’s Regional Director for East and Southeast Asia.

“It is not safe to be poor in President Duterte’s Philippines. All it takes to be murdered is an unproven accusation that someone uses, buys, or sells drugs. Everywhere we went to investigate drug-related killings ordinary people were terrified. Fear has now spread deep into the social fabric of society.”

For the findings in Amnesty International’s report, titled “They Just Kill”, the human rights NGO’s researchers conducted a field study in April and subsequent remote follow-ups in April and May. The researchers found that victims of the drug-related killings examined by Amnesty International were overwhelmingly from poor and marginalised communities, saying that this was in line with past research findings showing that the government’s anti-drug efforts chiefly target the poor.

Amnesty International interviewed 58 people, including witnesses of extrajudicial executions, families of victims, and local officials.

To make matters worse, the allegedly targeted poor are made to suffer even after the loss of their loved ones. The report noted that staggering costs of burial and other funeral services, for example, have left many families scrambling to borrow money or ask churches or local politicians for help to be able to lay their loved ones to rest.

The bill being pushed forward states that funeral homes granting discounts or free services to indigent beneficiaries or extremely poor beneficiaries may reimburse the cost of the discount from any regional offices of the Department of Social Welfare and Development (DSWD) upon the approval of the regional director or convert the same as tax credits, for as long as a proper certification as to the veracity of the claim is certified true and correct by the DSWD.

Tax credit may be used for a period not exceeding five years from the day the discount was given or from the date appearing in the official receipt, while the amount necessary to implement the provisions of this Act shall be charged against the allocation in the General Appropriations Act of the DSWD.

It is clear that if this alleged targeting of the poor in the drug war continues, then it makes passing this bill extremely important.

Related articles: