A recent report has pitted the Philippines as one of the most dangerous countries in the world, positioning it next to the likes of conflict-ridden Syria and Yemen.

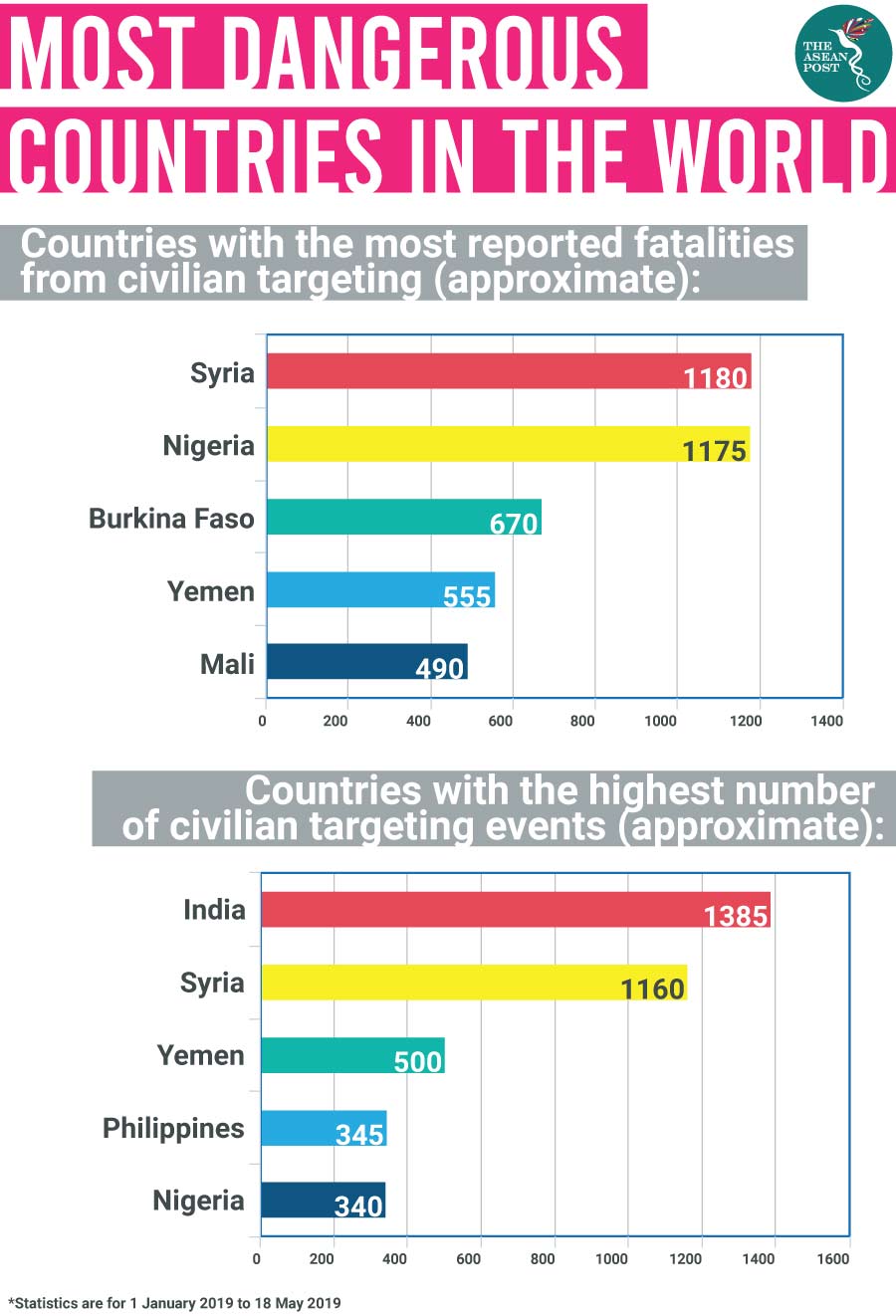

The report, entitled “Fact Sheet: Civilians in Conflict” by Sam Jones and Melissa Pavlik from the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED), placed India as the most dangerous country, with 1,385 violent events that targeted civilians. In second place is Syria with 1,160, followed by Yemen with 500, and the Philippines with 345. Nigeria was placed fifth with 340 events.

The findings of the report, gathered between 1 January 2019 to 18 May 2019, lend legitimacy to concerns voiced by several human rights observers regarding Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte’s “War on Drugs”.

Meanwhile, the confirmed death toll of suspects killed in anti-drugs operations currently stands at 5,425 since July 2016. Michelle Bachelet, United Nations (UN) high commissioner for human rights, has taken note of the gravity in that number.

“The extraordinarily high number of deaths – and persistent reports of extrajudicial killings – in the context of campaigns against drug use continue. Even the officially confirmed number of 5,425 deaths would be a matter of most serious concern for any country,'' she was reported as saying less than a month ago.

More recently, Amnesty International released a report in which it accused Duterte’s War on Drugs as being nothing more than a “large-scale murdering enterprise”, claiming that the poor were often the ones being targeted.

“It is time for the United Nations, starting with its Human Rights Council, to act decisively to hold President Duterte and his government accountable,” said Nicholas Bequelin, Amnesty International’s Regional Director for East and Southeast Asia.

“It is not safe to be poor in President Duterte’s Philippines. All it takes to be murdered is an unproven accusation that someone uses, buys, or sells drugs. Everywhere we went to investigate drug-related killings ordinary people were terrified. Fear has now spread deep into the social fabric of society.”

Targeting the poor

For the findings in Amnesty International’s new report, entitled “They Just Kill”, the human rights NGO’s researchers conducted a field study in April and subsequent remote follow-up in April and May. The researchers found that victims of the drug-related killings examined by Amnesty International were overwhelmingly from poor and marginalised communities, saying that this was in line with past research findings showing that the government’s anti-drug efforts chiefly target the poor.

Amnesty International interviewed 58 people, including witnesses of extrajudicial executions, families of victims, and local officials. According to Amnesty, families had described how victims who struggled to earn a living were accused of allegedly being “big-time” operators.

“How come big-time? My husband? And he needs to [work] overtime… to support me and my children?... I don’t understand. Only the poor, only the poor they want to kill,” the wife of a man who was shot dead by police in late 2018 told the human rights group.

“In practically all the cases examined by Amnesty International, families said their killed loved ones did not own a gun and would not have even known how to use one. Many said those killed were too poor to own a firearm. In the words of one victim’s mother: ‘If he had a gun, he would have sold it because he can’t even buy food.’,” Amnesty International said in its report.

To make matters worse, the allegedly targeted poor are made to suffer even after the loss of their loved ones. The report noted that staggering costs of burial and other funeral services, for example, have left many families scrambling to borrow money or ask churches or local politicians for help to be able to lay their loved ones to rest.

“Families in Bulacan told Amnesty International they were asked by funeral homes to pay anything between 20,000 (US$380) to 75,000 pesos (US$1,420) for their services. At times, bodies stayed in the morgue for several days before families could afford to retrieve them, some relatives said. Others pointed to the practice of extending wakes and hosting gambling in them for days to raise money for the burial, at the risk of the bodies starting to decay,” the report said.

If it is true that the poor are the ones being targeted in Duterte’s War on Drugs, and the Philippines is one of the most dangerous countries in the world, then this would make the Philippines the most dangerous country in ASEAN for the poor. Sadly, human rights observers and political pundits believe that it was this call to arms that won Duterte the administration in the first place.

On 17 June 2019, Amnesty International sent a letter to the Philippine National Police (PNP) requesting information regarding their antidrug operations. At the time of the report’s publication, there has still been no response.

Related articles: