Last week, local media in Indonesia broke a story that 14 students with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), had been expelled from a public elementary school following demands from parents of other students.

The headmaster of the Purwotomo Public Elementary School who, like many Indonesians, goes by the single name Karwi, told local media that the students in question had not been allowed to attend classes – in the town of Solo in Central Java province – since last week.

He said that the school’s explanation on how HIV is transmitted failed to convince the concerned parents, who threatened to move their children to another school if it did not expel the students suffering from HIV.

How discrimination propagates HIV

Discrimination against people with HIV or acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) is known as serophobia. The irony here is that, according to several studies, this discrimination actually propagates the disease.

According to a study from the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) in 2017, titled “Agenda for zero discrimination in health-care settings”, stigma and discrimination manifests itself in many ways. Discrimination and other human rights violations may occur in health care settings, barring people from access to health services or enjoying quality healthcare.

Similarly, two studies in 2013 published in the Journal of the International AIDS Society (JIAS); “A systematic review of interventions to reduce HIV-related stigma and discrimination from 2002 to 2013: how far have we come?” and “Impact of HIV-related stigma on treatment adherence: systematic review and meta-synthesis”; found that some people living with HIV and other key affected populations are shunned by family, peers and the wider community, while others face poor treatment in educational and work settings, erosion of their rights, and psychological damage. This in turn could lead to limited access to HIV testing, treatment and other HIV services.

Another 2017 report by UNAIDS, entitled “Confronting discrimination: overcoming HIV-related stigma and discrimination in health-care settings and beyond”, stated that people living with HIV who experience high levels of HIV-related stigma are more than twice as likely to delay enrolment into care than people who do not experience HIV-related stigma.

UNAIDS executive director Michel Sidibé, who launched the report during the Human Rights Council Social Forum in October that year, said that when people living with, or at risk of, HIV are discriminated against in health-care settings, they go underground. This, he added, seriously undermines the ability to reach people for HIV testing, treatment and prevention services.

“Stigma and discrimination are an affront to human rights and puts the lives of people living with HIV and key populations in danger.”

Discrimination in Indonesia

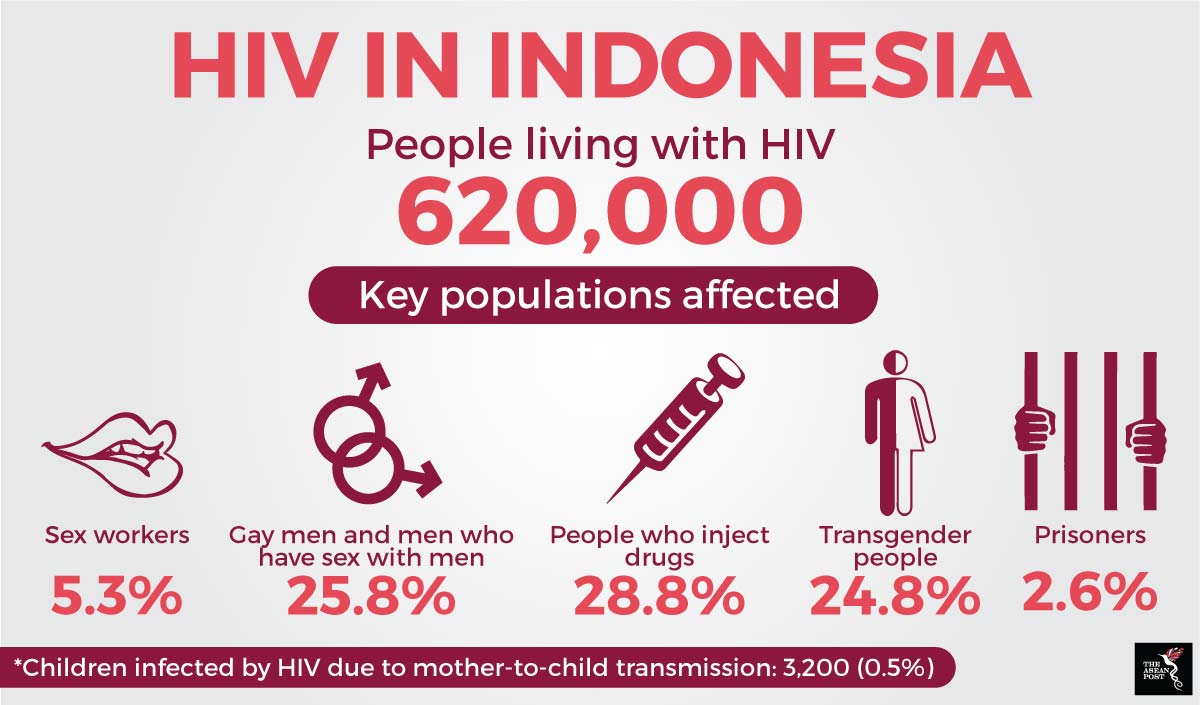

UNAIDS states that in 2016, there were approximately 620,000 people living with HIV in Indonesia. Of this number, key populations most affected by HIV were: sex workers (5.3 percent), gay men and other men who have sex with men (25.8 percent), people who inject drugs (28.8 percent), transgender people (24.8 percent), and prisoners (2.6 percent).

Looking at the key populations affected, it is easy to understand why Indonesia – which is facing a rise in Islamic conservatism – would have a stigma against those who suffer from HIV. In fact, a study funded by the Fogarty AIDS International Training and Research Program (AIRTP) at the University of Illinois at Chicago (UIC) in 2014, also found that religious beliefs were one of the reasons for HIV discrimination among Indonesian nurses.

According to the study, “Understanding HIV-related stigma among Indonesian nurses”, a nurse’s religion, degree of involvement in religion, and the religious affiliation of the workplace contributed significantly to stigma toward those suffering from HIV and populations at risk of HIV. It also stated that the stigma was strongest among Muslim nurses, although the stigma among Catholic and Protestant nurses was also high.

“This may reflect the relative intensities of the sanctions against homosexuality and drug use in these religions. It may also have reflected the relative assertiveness of religious attitudes in a society where Muslims are a majority.”

Source: UNAIDS

Source: UNAIDS

What is important to note based on the data from UNAIDS, however, is that while the key populations affected by HIV were from groups which most conservatives shun, an estimated 3,200 children were also newly infected with HIV due to mother-to-child transmission. Which means that even the completely innocent can become victims.

Education versus exposure

Another interesting finding in the study funded by the AIRTP was that improved HIV knowledge did not automatically mitigate stigma. Instead, the study seemed to suggest that the answer to combating stigma against HIV was more exposure to diversity.

This conclusion could be made when, according to the study, religion was not the only reason behind the stigma. Rather, the data suggested that stigmatising attitudes thrive in workplaces that are culturally, religiously, and educationally homogeneous.

“As a case in point, nurses who practiced a religion that differed from the religious affiliation of their employing institution were also the most likely to come from the Catholic hospital where a large proportion of nurses (41 percent) were non-Catholic,” the study says.

The study found that in these hospitals where there was more diversity present, stigma towards people suffering from HIV was significantly lower.

It would be worth the Indonesian government’s while to look deeper into the possibility of using exposure to diversity in order to combat the discrimination and stigma associated with HIV. If this turns out to be true then it may also be worthwhile to find ways to expose people to a wider array of cultures and religions because, as studies have shown, combating stigma could also mean combating HIV in the long run.

Related articles:

Indonesia’s HIV rates on the rise