Women’s hair is her crowning glory – even when the hair is not her own. Hair extensions have become an essential segment in the multi-billion-dollar hair industry, with an estimated annual sales range from US$250 million to over US$1 billion. Based on a 2018 Research and Markets report, the global hair wigs and extension market is estimated to reach revenues of more than US$10 billion by 2023.

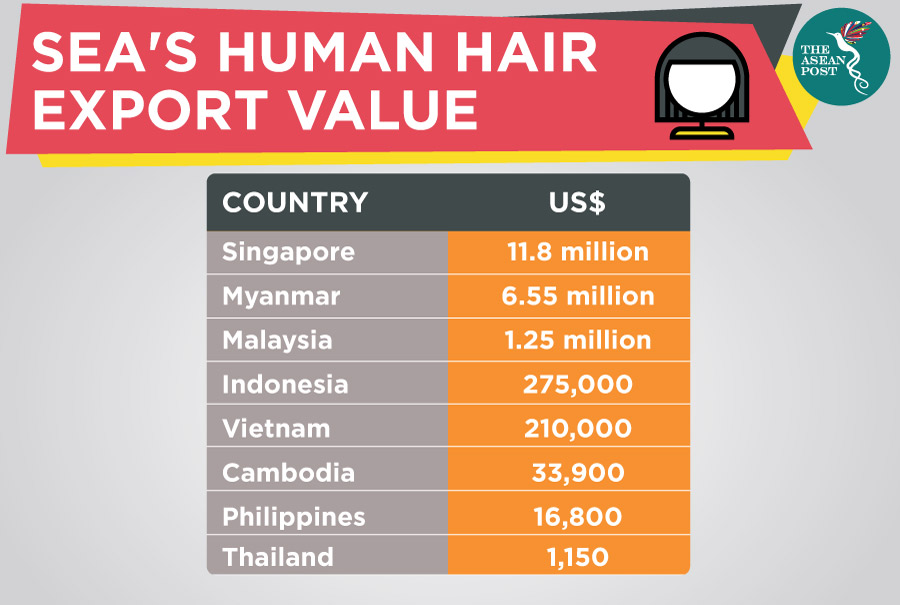

Raw human hair has significant commercial value and is a coveted commodity in international trade to be processed into hair extensions and wigs. According to a report by the Observatory of Economic Complexity (OEC), the global value for human hair export in 2017 was US$126 million. Asia exported a value of US$72.4 million, accounting for 58 percent of the overall global trade.

Raw human hair is collected by harvesting directly from the heads of women, and the human hair trade is a profitable niche. In India, the Tirupati Balaji temple earns 10 percent of its income through the auctioning of human hair that was donated to the temple by devotees. The temple makes a profit of US$25 million to US$40 million a year.

There are three categories for collected hair which are Remy, non-Remy and virgin hair. Remy is usually obtained from temples through donations and is of the highest grade. Non-Remy hair is a lower grade hair collected through individuals and hair are typically broken or short. Virgin hair is hair that has never been chemically treated.

In Southeast Asia, long hair is esteemed as a mark of beauty with deep religious and social meaning, especially in Buddhist-majority countries. In Myanmar, the hair trade is a lucrative business with earnings of US$6.2million in 2017. However, across Southeast Asia, the human hair trade is not regulated, allowing traders to source their hair through unfair means.

Exploited

While most brands have opted to acquire hair from India where most hair is donated for religious rites, in Southeast Asia, traders target impoverished areas to buy hair from desperately poor people. Their desperation makes them easy prey for exploiters. Hair extensions in the US can cost between US$500 and US$2000, but the owner of the hair may only receive a tiny fraction of that cost.

For example, Vietnamese Nguyen Thi Thuy told Lexy Lebsack of Refinery29, that the highest she has ever been offered for her hair is VND70,000 (US$3). According to a recent article written by Erica Ayisi in partnership with the Pulitzer Centre, titled, ‘Made in Cambodia: How women in poverty are supplying America's market for hair,’ Cambodian women can get at least US$15 for their locks.

Soeng Sen Karuna of the Cambodian Human Rights and Development Association told Ayisi that the women don’t know how to bargain over the price of hair, “[t]hey decided to sell their hair because they are poor, and they don’t know where to sell their hair for international market price.”

Cambodians are still struggling to make income and send their children to school. According to the World Bank, 4.5 million Cambodians are near-poor, with 90 percent of them living in the countryside.

In the article, Sen Karuna said that if the hair trade were to continue, the government should think about the people and not allow excessive exploitation to take place.

Unfortunately, demand exceeds the supply. The high value of human hair has made hair-theft muggings a recurrent problem for some countries. Some companies have resorted to using fake hair through chemical processing or use a mixture of human hair with goat hair.

Ethical sourcing

The increased awareness exploitation in the trade has shifted many companies to collect their human hair from more transparent and ethical sources. Janice Wilson’s, now defunct start-up, Arjuni, dealt directly with customers, eliminating the added cost of a middle-men. She employed women who were victims of sex-trafficking and taught them how to manufacture the collected hair and even English and maths so they can have the opportunity to become managers.

Wilson now runs Mane Moguls for hair industry entrepreneurs looking for more insight into the hair extension business. Her program includes a module about ethics on the ground.

Another start-up that promotes fair trade in human hair is Remy New York by founder, Dan Choi. To ensure transparency, the start-up allows third parties to follow its supply chain and access to the women who sourced the hair.

The start-up also offers women higher prices for their hair, ranging from US$65 to US$200. After agreeing upon a rate, Choi would section and cut the hair himself. In Vietnam, Choi bought hair from Thuy and paid her US$100 for her hair, which is enough for her to purchase livestock to raise for years to come.

While the human hair trade has provided many communities with income and opportunities, practices that exploit and deprive women of opportunities must stop. Regulations and fair trade will empower women to thrive in the industry and perhaps when technology advances, synthetic hair may one day match those of humans.

Related articles: