Natural gas has made up 40% of ASEAN electricity generation since 2000, according to the Southeast Asia Energy Outlook report 2017. Now, this volume of natural gas demand is set to grow, with electricity demand climbing by 6.1% across Southeast Asia annually, and more than doubling in Cambodia, Indonesia, Vietnam and Myanmar, according to the same report.

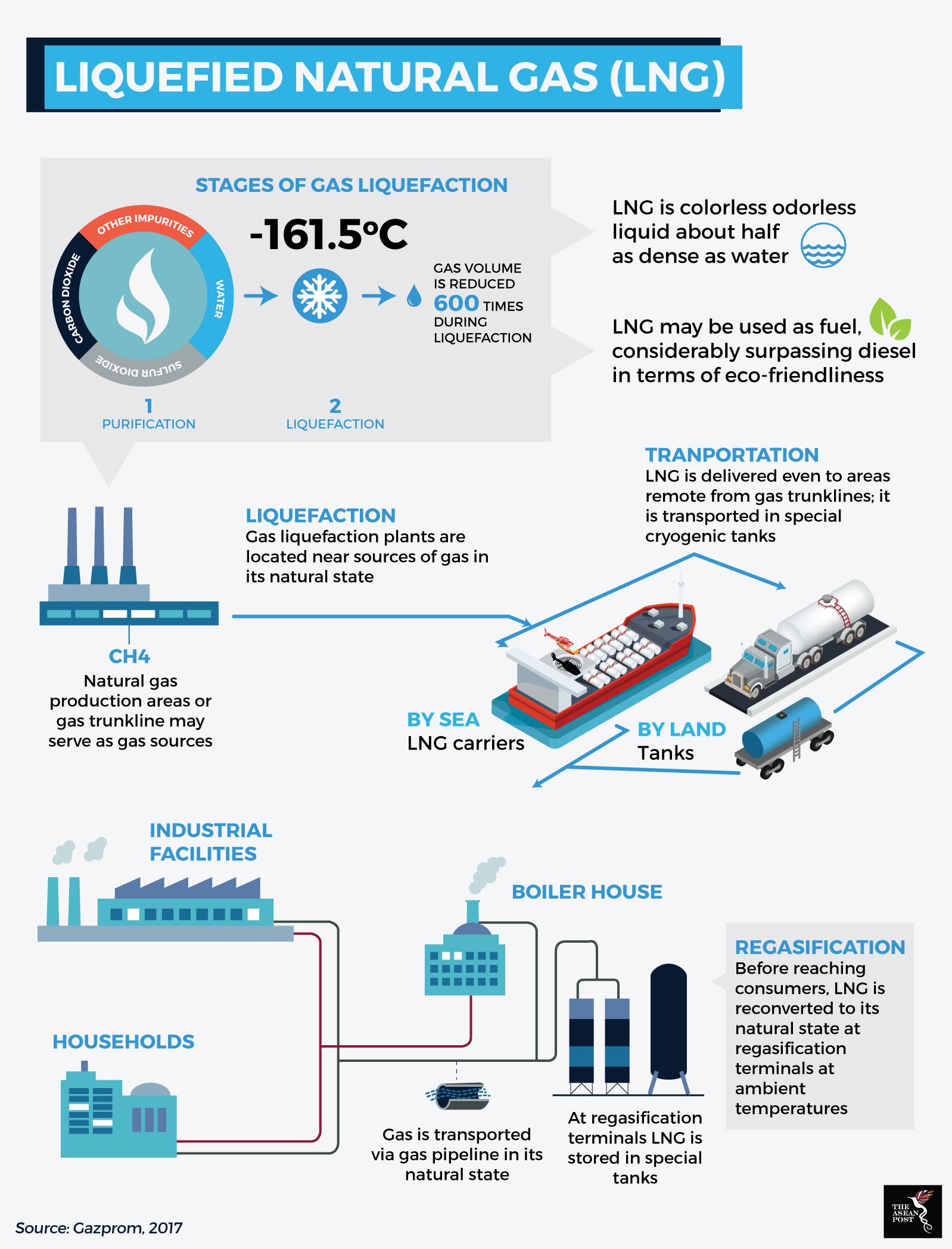

Natural gas that is cooled to a temperature of about -162C (-260F) produces a clear, colourless liquid known as liquified natural gas (LNG). The cooling process also shrinks the gas volume by 600 times. Natural gas is converted to LNG to allow for easier transportation and storage where pipelines is not technically or economically feasible to lay down (source)

Rising electricity needs raises LNG demand

According to highlights from the Southeast Asian Outlook 2017, Southeast Asia is playing an increasingly prominent role as a market for liquified natural gas (LNG). Thailand, Indonesia, Vietnam, the Philippines and Singapore were expected to triple their imports of LNG between 2017-2020, according to BMI Research in 2017.

Thailand and Singapore are already large importers while Vietnam and Philippines, currently self-sufficient, will soon need to begin importing. Thailand is expecting imports of LNG to grow sevenfold to hit 35 million tons a year by 2036, while Indonesia, currently a net exporter of LNG, could become a net importer even as local production was expected to fall below the level of local demand by 2020, according to reporting by Reuters in 2017.

LNG infrastructure developments in SEA

Import, or regasification terminals are fast being built in the region in a bid to increase the flexibility of gas procurement as well as create sustainable LNG supplies.

The Philippine National Oil Company (PNOC) signed an agreement with the Asian Development Bank (ADB) in January this year whereby the latter would act as transaction advisor to PNOC's first LNG hub project in Batangas. The project includes the development of a regasification terminal, storage and power plant and is aimed at replacing existing gas resources. The Philippines’ domestic gas reserves at the Malampaya gas field in Palawan is expected to last only till around 2027 or 2029, according to Cesar Romero, a Shell country manager in 2017.

Myanmar recently received US$5 billion in investment from a French energy company and Chinese supplier to fund three new LNG power plants. These would provide up to 3000 megawatts of electricity capacity after development is completed in the next three to four years, according to reporting by the Nikkei Asian Review in February this year. Myanmar, though possessing large natural gas resources has suffered from domestic LNG shortages due in part to long-term sales contracts of natural gas to China and Thailand. Although Myanmar can’t afford to invest into infrastructure at the moment, it will still be able to develop LNG terminals using investment funds from foreign firms.

Despite wide infrastructural ambition in these countries, supporting frameworks is also needed to create sustainable LNG capacity. Singapore, for instance has created a liberalised gas market, opened channels to international pipelines and allowed third-party access to its LNG infrastructure as part of its efforts to become a trading hub for LNG in the future.

Indonesia, on the other hand, is encouraging production of LNG through some small-scale regasification terminal projects, in an effort to power its various scattered islands. The volume of demand for LNG from these small-scale projects is expected to amount to 3.5 million mt/year- to 4 million mt/year, according to energy research and consulting group Wood Mackenzie. This only constitutes 10% of overall forecast demand for LNG in the region, which raises the question of financial viability.

"Technically, small-scale LNG is very effective, but not commercially viable. Indonesia needs more industries besides PLN (Perusahaan Listrik Negara) to use LNG," commented Salis Aprillian, a Pertamina strategic advisor in February this year.

Scattered volumes raises the costs of labour, gas distribution pipelines and transportation costs, creating a sort of diseconomies of scale. According to Aprillian, increasing the financial viability of small-scale projects will require Indonesia to create more downstream uses for gas, and build gas demand hubs in order to reach new sectors.

On a regional scale, what is still needed is also better interconnection of LNG pipeline networks between ASEAN countries in order to facilitate a more coherent market and better prices for LNG. This is because ASEAN countries currently have fragmented strategies in pricing their gas supply output, which potentially creates uncertainty for foreign investors looking to invest in LNG infrastructure in this region. Since Southeast Asia’s LNG demand can only grow from here, it would be prudent for ASEAN to consider such a collaboration as early as possible.

Recommended stories:

-

Need for regulation grows in tandem with e-payments push in Southeast Asia

-

The Philippines tops energy ranking for environmental sustainability