In a recent report, it was found that 22 million people in Indonesia suffered from chronic hunger between the years 2016 and 2018.

The report also acknowledged that there was strong growth in Indonesia’s agricultural sector and the country’s overall economy over the past several decades. Despite significant strides in the sector, however, many people across the country are still engaged in traditional agriculture as they are trapped in low-paid activities. This fact, in turn, leads to hunger and increased risk of stunting among children.

“Many [Indonesians] do not get enough food and their children are prone to stunting, keeping them in a vicious cycle for generations. From 2016 to 2018, about 22 million people in Indonesia still endured hunger,” the report says, referring to the first term of President Joko "Jokowi" Widodo.

Titled “Policies to Support Investment Requirements of Indonesia’s Food and Agriculture During 2020-2045”, the report by the Asian Development Bank (ADB) and the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) with support from Indonesia’s National Development Planning Agency (Bappenas), was published last month.

The report further noted that issues such as unequal access to food and food insecurity have remained unresolved in the country. This was despite increasing trends in food production and availability, as well as increases in household incomes.

In fact, it was reported last year that poverty in Indonesia declined to the lowest level ever in March 2018. Based on the latest data by Indonesia's Central Statistics Agency (BPS), Indonesia's relative poverty figure fell to 9.82 percent of the total population during that period.

The BPS releases poverty figures twice per year, covering the months of March and September.

Rankings

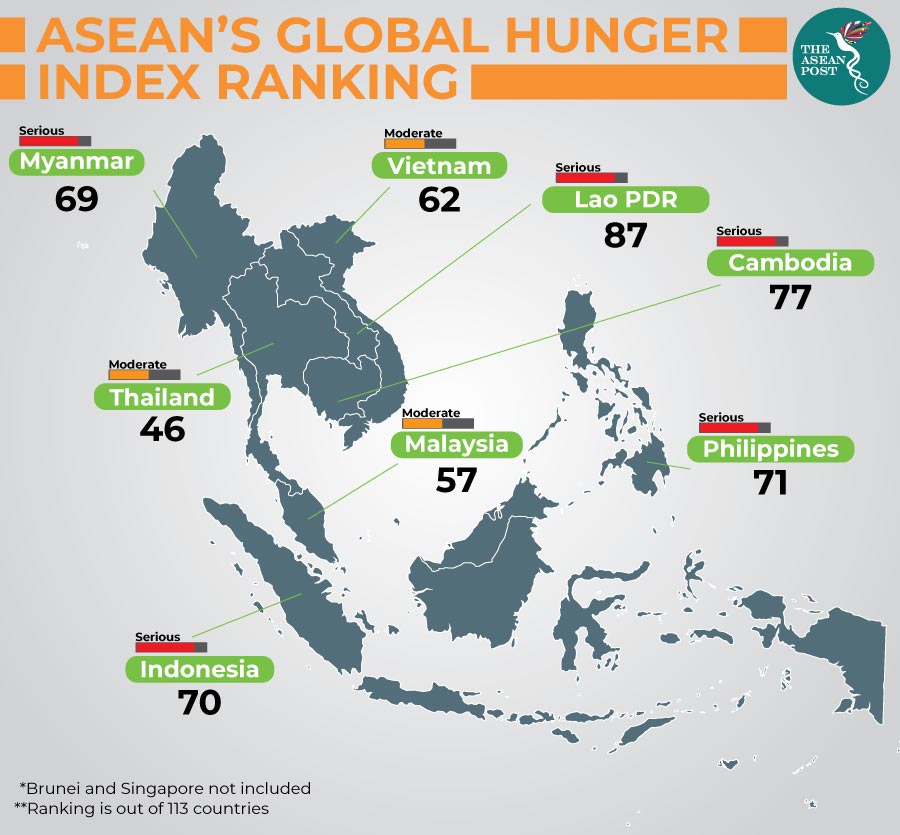

In February, The ASEAN Post published an article about hunger among the children of ASEAN. That article took note of the Global Hunger Organisation’s (GHO) 2018 results for the Global Hunger Index (GHI) which showed that ASEAN’s member countries were still relatively hungry.

In the case of Indonesia, while the country was not the worst in ASEAN, its position was not one it could immediately be proud of. Of the 119 countries surveyed, Indonesia was ranked 73rd, falling behind other ASEAN countries like Thailand (44th), Malaysia (57th), Vietnam (64th), Myanmar (68th), and the Philippines (69th).

For the 2019 GHI, Indonesia managed to obtain a better score but only marginally, and perhaps the fact that poorer countries were also included in the survey had something to do with this. Out of 117 countries, Indonesia was placed 70th which was still worse than Malaysia (57th), Myanmar (69th), Thailand (46th), and Vietnam (62nd).

Food security rankings for the country were not the best either. In a separate study published by the Economist Intelligence Unit, Indonesia was ranked 65th among 113 countries in the Global Food Security Index (GFSI). This rank was below other ASEAN nations such as Singapore which came in first on the index, Malaysia which came in 40th, Thailand which came in 54th, and Vietnam which came in 62nd.

The GFSI was cited in the “Policies to Support Investment Requirements of Indonesia’s Food and Agriculture During 2020-2045” report.

The report also advised increased investment in agriculture to modernise food systems as one of the other possible solutions to the persistent problems the country was facing in addressing hunger as well as food security.

“Such investment will not only help improve the country’s food production but will also enable households to engage in more productive sectors and earn a better income,” the report added.

Despite Indonesia’s problems, the report does not necessarily paint a bleak future for the Southeast Asian country. In fact, based on the survey results, the report says that Indonesia could virtually end hunger by 2030 and fully eradicate hunger by 2045. Nevertheless, this would require effort on the part of relevant stakeholders, which includes investments in agricultural research and development (R&D), irrigation expansion and water use efficiency, as well as improved rural infrastructure including roads, electricity and railways.

Related articles: