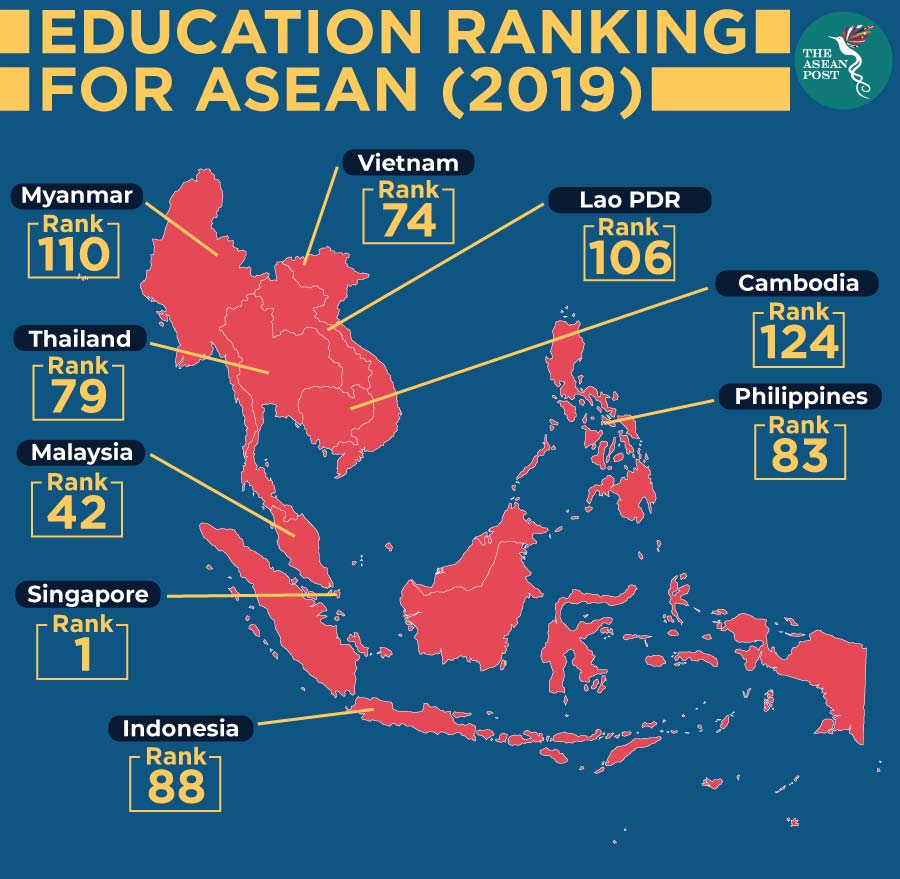

Indonesia has a big problem in facing the challenges of the 4th Industrial Revolution. The quickly evolving landscape and potential requirements on the country’s skilled workforce is becoming a major concern. Indonesia, ASEAN’s largest economy, could be running out of time to equip its people with the necessary skills, attitudes and knowledge to stay competitive. The country has already highlighted a talent shortage of more than 50 percent as its biggest concern. Let’s take a closer look at the magnitude of this problem and its underlying causes.

Today Indonesia has the highest youth unemployment rate in the region, at about 15 percent, according to data from the World Bank. In addition, many young university graduates find no other option than taking jobs which do not require any university qualification. At the same time, many workplaces requiring advanced skills cannot find university graduates qualified enough for the jobs due to a skill gap which today exists in Indonesia. The gap is between what universities are preparing the graduates for and what many workplaces need.

According to studies conducted by the Global Business Guide (GBG), Indonesia currently has 4,498 universities and 25,548 majors, yet the country's higher education institutions still rank poorly at the global level. The report notes that quality has long been of concern to policy makers in Indonesia's higher education sector. For example, at the end of 2017, only 65 out of nearly 4,500 universities held A Grade accreditation status. Most of the underperforming universities are privately owned and offer substandard educational services which in turn produce poor quality graduates. The report concludes that this is one of the main reasons behind the high unemployment rate among Indonesian graduates which has continued to increase from 374,868 in 2016 to 463,390 in 2017. It is this alarming trend that has driven the Ministry of Research, Technology and Higher Education to announce plans to close or merge 1,000 private campuses in 2019.

According to GBG analysis reports, another major shortcoming of Indonesian universities is the lack of qualified faculty members. The majority of lecturers in Indonesia or 155,519 only hold a master's level degree, followed by those with a bachelor's degree accounting for 34,393, those with a doctorate degree equate to 31,554, and those with a professorship only number 5,389. In fact, it is widely predicted that Indonesia will soon experience a lecturer shortage crisis as more than 6,000 lecturers will retire in 2021 at a rate of 1,000 to 1,200 a year.

The government is well aware of this desperate need for high-skilled talent. In July, Mohamad Nasir, Indonesia’s Minister of Research, Technology and Higher Education, urged all higher education institutions to produce competent graduates in line with industry demands. However, achieving this will be very challenging since the root of the problem is of a complicated socio-political nature and also involves the whole education sector – from kindergarten up to universities.

A report titled, “Beyond access: Making Indonesia’s education system work” from the Sydney-based Lowy Institute last year, claims that Indonesia’s education system is low in quality, well short of the country’s ambition for an internationally competitive system, and the underlying causes are political. The report argues that the “politics and power” dominance over the education system makes any real and substantial reforms difficult. Assuming that Indonesia can overcome the “politics and power” challenges by exercising a firm socio-political leadership from the highest political instance, the challenges can be addressed by much needed comprehensive reforms within the entire educational system.

On a positive note, to improve the quality of local universities, the government has been encouraging reputable, foreign universities to open branches in Indonesia or team up with local universities. The Ministry of Research, Technology, and Higher Education announced in September 2018 that two Australian universities have obtained approval to open their branches in Indonesia. Many campuses have partnered with foreign universities through lecturer and student exchanges, grants and scholarships, dual degree programs, joint research, training, and publications.

The demand for high-quality tertiary educational services in Indonesia will continue to grow in the foreseeable future as 43 percent of the country’s population are below 25 years old and the middle-class population is expected to double to 140 million by 2030. President Jokowi’s efforts to revamp the country’s education sector is highly commendable and it is worthwhile to look at the prospects and potential of one of the targeted strategies i.e. e-education which would allow more people access to education, and also help alleviate youth unemployment challenges.

New research by Cambridge International, the first ever Global Education Census which was released in November 2018, reveals that Indonesian students are among the world’s highest users of technology in education. Indonesian students are also the most eager to become entrepreneurs, compared to their global peers. The number of internet users in Indonesia increased by 10 percent last year, according to a recent study by Polling Indonesia conducted in cooperation with the Indonesian Internet Providers Association (APJII). The study shows that 171 million people, or 64.8 percent of the total population of 264 million Indonesians, were already connected to the internet in 2018. The figure represents an increase from 54.86 percent recorded in 2017.

The Indonesian government's efforts to take full advantage of this new trend by encouraging universities to actively pursue e-education can help accelerate the country’s path towards becoming a knowledge-based economy and in addressing the challenges of youth unemployment. The burgeoning tech start-up ecosystem in Indonesia and e-education that is developed by universities in partnership with stakeholders from the business sector, can create graduates that are entrepreneurial and have the needed attributes to either be employed or self-employed in pursuing their own innovations.

Improved quality of education in Indonesia will require honest political will to put in place a comprehensive set of actions. This set of actions needs to start with eliminating the dominance and control of political, and bureaucratic elites, over the education system and by holding back the current political and social forces opposing real and substantial educational reforms. Instead, stakeholders from a diverse spectrum should be invited to participate in the reform processes by sharing their practices and experiences and to jointly form a new, progressive education policy and system for Indonesia. Any reform of the current education system must consider that education is an ecosystem with many key stakeholders.

President Jokowi should personally lead this task in order to give it much needed weight and attention. The issues needed to be discussed in order to come up with a national plan/agenda for the transformation of the entire education system in Indonesia, are adequate funding, management of schools and universities, roles of teachers and schools- and academic leaders, teacher education and training programs, curriculum design, use of new technologies such as artificial intelligence in education, individualisation of the education system, flexibility taking into account evolving societal requirements and individual learning needs, among others.

The time is now and any further delay in this, will have irreversible effects on Indonesia and its position in the global economy.

Related articles: