The Indonesia Millennial Report 2019 has revealed an encouraging discovery: despite the numerous reports on a supposed increase in conservatism in the country, some 89.1 percent of the millennial generation have an optimistic outlook on diversity in Indonesia.

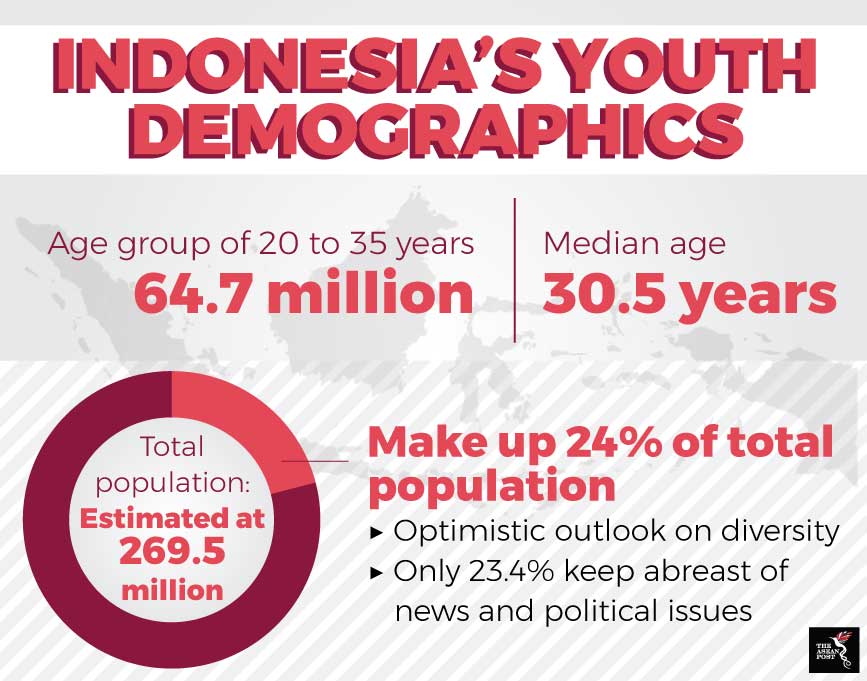

The report defined millennials as those belonging to the age group of 20 to 35 years. It noted that some 24 percent of Indonesia’s population is made up of millennials. The voting age in Indonesia is 17.

According Winston Utomo, Founder and Chief Executive Officer of IDN Times, the Millennial Summit 2019 is an independent meeting aimed at shaping a better future for Indonesia by involving various stakeholders or related parties, including the government, industry players, and the community.

"The more people who see this data, the better. This will enable people to join hands and work together to make Indonesia better in the future," Utomo said during the Indonesia Millennial Summit 2019 in Jakarta on Saturday.

The overwhelming number of millennials who have an optimistic view on diversity is especially pertinent due to the presidential election that is slated for April. Many observers have noted that millennials will make up a very important voting bloc in the upcoming election.

According to Syafiq Hasyim, a visiting fellow at the Indonesia Programme of the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS), Singapore; the millennial population in Indonesia currently forms about 34.5 percent to 50 percent of the total population. Differing from the Indonesia Millennial Report 2019, Syafiq defines millennials as those aged between 15 to 35 years.

Barking up conservatism

Unfortunately, as numerous observers and analysts have noted, both presidential candidates –incumbent Joko “Jokowi” Widodo and Prabowo Subianto – may be barking up the wrong tree in their attempts to appeal to the country’s conservatives.

While Jokowi’s appointment of controversial and conservative cleric Ma’ruf Amin as his running mate made his intentions obvious, Prabowo at least seemed to start off on a more moderate and progressive footing, even appointing young businessman Sandiaga Uno as his running mate.

However, Prabowo’s appearance in a rally early last month raised some eyebrows. The rally’s organisers called it a “reunion” for a series of rallies starting in late 2016 that targeted Jakarta governor Basuki Tjahaja Purnama, also known as Ahok, who was charged with insulting the Quran.

Source: Various sources

Source: Various sources

Prabowo’s appearance at the rally begs the question as to whether he will use anything at his disposal – including a growing religious conservatism – to win in the coming election. In fact, Ray Rangkuti, an Indonesian political analyst, believes that political figures in the country are increasingly willing to find common ground with conservative and even extremist Muslim organisations in pursuit of personal political gains.

Disenchanted youth

Syafiq writes that Indonesian millennials will determine the outcome of the Indonesian presidential election due to their significant size.

“The presidential candidates who are able to think, absorb and accommodate their aspirations would probably be well placed to win,” he says.

There is a problem, however. Internal research carried out by Prabowo’s campaign team shows that half of the country’s millennials are unlikely to vote because they see politics as what Sandiaga refers to as "too dirty and too boring."

“About 50 percent of millennials are pretty much disengaged, they are disenfranchised and not too interested in politics. We need to continue to work hard and pound the issues that are relevant to them and we need to convince them, otherwise, they won't come to the voting booth," Sandiaga was quoted as saying.

On the one hand, the presidential candidates must ask themselves whether harping on matters of conservatism could be contributing to the turn-off from the millennials. On the other hand, millennials who wish to see a change in their country must voice their aspirations and show these candidates that they are a strong enough force for the candidates to switch their strategies to that which incorporates more inclusiveness and openness.

Even if – as many analysts have pointed out – conservatism is on the rise in Indonesia, the fact that millennials are optimistic about diversity should give pause to those hoping to become the country’s leaders.

Related articles: