An analysis of 65 countries has found that only 20 percent of the world's internet users enjoy "free" access according to international watchdog organisation, Freedom House. The remaining 32 percent are "partly free" and 35 percent are "not free", while 13 percent of users have yet to be assessed.

The declining freedom of the internet in ASEAN highlights some serious concerns for its citizens in terms of privacy and ownership of data. The concept of digital rights is not simply about an individual’s right to access the internet. The violation of an individual’s digital rights also includes targeted violence, prosecution, and suppression.

The level of internet freedom in each country is analysed under three sections. The first is "obstacles to access" which includes the ease and cost of getting connected, and whether different groups of people have equal access in the same country. For example, marginalised groups in the northern state of Rakhine do not have equal access to the internet as other people in Myanmar, due to a 7-month long internet blackout.

The second section is "limit on content", which looks into the websites that are being blocked and assesses if contents have been removed. This also includes the manipulation of content by governments. For example, the Philippines has seen a rapid increase in content manipulation in the past couple of years. “Content manipulation got even worse during the 2019 elections where tactics that were being used were even more insidious and targeted compared to the 2016 elections,” Freedom House, research analyst, Allie Funk told The ASEAN Post.

Journalists are one of the major groups being targeted by the government of the Philippines. Journalists there are now practicing self-censorship due to the high level of violence against them and the increasing number of civil and criminal cases related to online activity.

The third section assesses the "violation of user rights" which encompasses human rights – online and offline. It covers some fundamental digital rights such as the right to privacy and right to free expression. Some governments use surveillance technology to target people for online speech or activities that are not in line with government propaganda with extreme measures of cyber-attacks, targeted violence, arrests and prosecution.

While prosecutions and removal of content is on the rise, the Philippines is more unique than other ASEAN countries in the sense that it does not block websites altogether.

Malaysia is one of 16 countries and only ASEAN country to show a positive improvement. This is due to the promises made by the new Alliance of Hope (Pakatan Harapan) coalition government that came into power in May 2018. Some local and international websites that had criticised the previous regime had duly been unblocked. In addition, the strong impact of cybertroopers and pro-government commentators on social media is slightly weakening too.

Nonetheless, "Malaysia still practices long-term prison sentences for those caught criticising race, religion and royalty. One example is a user who was sentenced to 10 years in prison for insulting Islam," said Funk.

Vietnam on the other hand, is by far the lowest ranking ASEAN country when it comes to internet freedom. In October 2018, the government announced the creation of the 'National Centre on Supervising Information', a unit which allegedly uses software to read 100 million items on social media platforms daily for analysis, evaluation and categorisation.

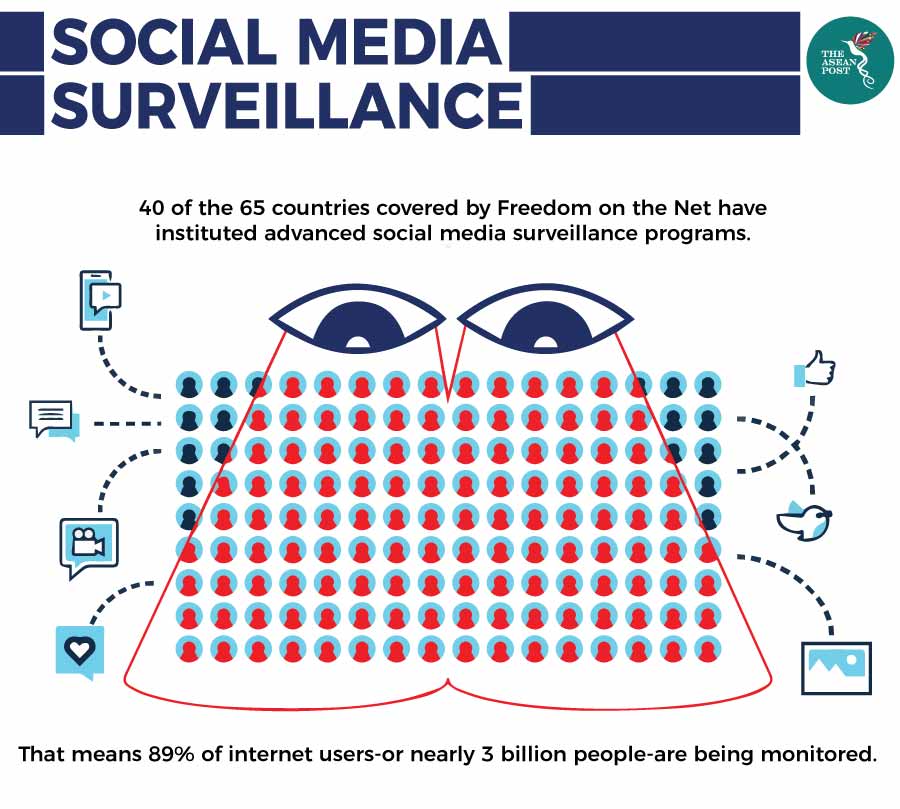

Across the globe, governments are using social media surveillance tools to collect and analyse vast amounts of data on their own citizens – the technology is driven by advances in artificial intelligence (AI) – and its success is expanding the private social media surveillance market. “These tools are becoming less expensive, where even local law enforcement across the United States (US) are using them and relatively small governments are able to buy them,” explained Funk.

An investigation by Haaretz, an Israeli newspaper found that in 2016, the government of Malaysia at the time allegedly purchased sophisticated technology from companies in Israel, with the ability to monitor and analyse social media and other open-source information. Whether the new government of Malaysia is still using the technology is not known. Other countries also listed in the investigation were Indonesia and Vietnam.

Another tactic is the use of pro-government commentators, which is common among some ASEAN states and an increasingly widespread method of propagating government rhetoric. There are no clear rules or policy on how it can be used by a government – hence its popularity.

“This is a dangerous practice and it is a significant threat to democracy. Speaking broadly, countries that don’t have a strong history of press freedom such as Vietnam and Myanmar have intense pro-government commentators, while in places like the Philippines that was traditionally “free”, are now trying to silence dissenting voices and push out independent news and control the narrative - particularly around big political events, such as elections or protests.”

International human rights laws are a sufficient basis for citizens to pressure their respective governments and resolve the breach of trust between governments and citizens in terms of digital rights. However, the lack of transparency in government practices in terms of data-based surveillance has kept ASEAN citizens in the dark on how their information is being retrieved or how governments are blocking, distorting, and manipulating the information they receive.

Related articles: