The term Islamophobia has its roots in the Greek word Phobos which refers to the God of fear and is used to denote terror. As such, the literal meaning of Islamophobia would be the ‘fear of Islam’. However, the term has evolved over the years to represent the many prejudices faced by Muslims by virtue of their faith. The modern interpretation is no more obvious than the recent Christchurch shootings. The shooter had no agenda other than prejudice and hatred towards Muslims. His misplaced determination and hatred gave him the strength to cross international borders to commit heinous crimes against innocent people.

Islamophobia is growing and the reasons for it may be closer to home than we think.

A probable source could be the media. Technology and the internet have allowed many unverified or fake news to reach hundreds of millions of people around the world. This was the case in Myanmar where many of the locals were led to believe that the Rohingya Muslims were indeed terrorists; fuelling a ‘slow-burning genocide’ as observed by Maung Zarni, a human rights activist.

Documented proof

There is documented proof that the media in general is highly skewed towards Islamophobic content. Dr Sadia Mahmood, an Assistant Professor from the Department of Mass Communication at the University of Karachi in her paper ‘Portrayal of Islam and Muslims on Facebook by US Conventional Media’ found that United States (US) media outlets are still negatively portraying Islam, not telling the full story and sometimes outright lying to their readers to instil a fear of Islam.

Nationalism or patriotism, whilst seen as a positive value, can sometimes be harmful to society. The violence perpetrated against the Rohingya Muslims is still seen as a righteous crusade against the ‘other’ by many in Myanmar. This form of nationalism is widely practiced in Myanmar today, reinforcing the belief that ‘Myanmar is for Buddhists’; the mantra of Ashin Wirathu, a Buddhist monk and leader of the anti-Muslim movement in the country.

Imtiyaz Yusuf, Associate Professor at the International Islamic University Malaysia, summarises the situation there nicely by writing that “it is a clash between two views (Buddhist and Muslim) of nationalism over the claim to Myanmar citizenship.”

“The conflict invokes Buddhist and Muslim nationalist in order to protect and preserve national ethnicities as religious identities in turn causing the rise of the new phenomena of Asian Islamophobia”, he explained.

Nationalistic sentiment

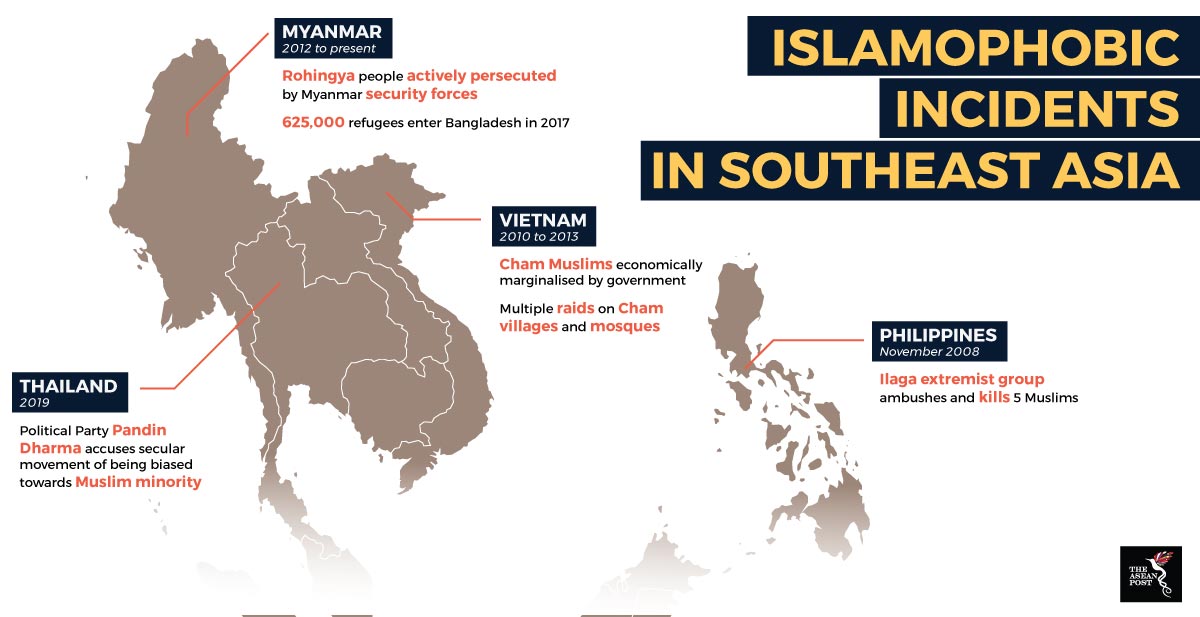

But sometimes, nationalistic sentiment can be traced back to society’s insecurities. US President Donald Trump used that very same tactic to win votes by proposing a “ban on all Muslims from entering the country” and making statements such as “Muslims were cheering when 9-11 happened” to appeal to Islamophobic parts of the population and white extremists. It is also happening within the borders of ASEAN member states. In Thailand’s recently concluded general election, Pandin Dharma, a political party obtained the support of Buddhist nationalist by claiming that the secular movement within the country was biased towards the Muslim minority.

Salman Sayyid, Professor of Rhetoric and Decolonial Thought at the University of Leeds, describes Thailand as one of the countries that is “feeling under threat from the demands of the Islamic people”.

The Rohingya crisis is an ongoing humanitarian disaster that has seen many Muslims living in Rakhine state having atrocities done to them by Myanmar’s security forces. The intolerable violence has forced them to flee to neighbouring Bangladesh.

ASEAN’s response to issues like the Rohingya crisis has not been the swiftest nor the most effective. The crisis started in 2012, but due to ASEAN’s non-interference policy, was only addressed in 2018 at the United Nations (UN) General Assembly, when member countries condemned the atrocities and called for the prosecution of those responsible. This came about after a year-long investigation by the UN that found six Myanmar generals guilty of crimes against humanity.

Social media company Facebook Inc. also took action by removing accounts of those linked to Myanmar’s military in order to curb the further proliferation of Islamophobic sentiments around the country. Alex Warofka, Product Policy Manager at Facebook admitted at the time that Facebook “needed to do more” in order to become “a force for good” in Myanmar.

Much more needs to be done to stop the spread of Islamophobia and ASEAN member states could learn from Canada where in 2017, members of the House of Commons tabled Motion 103 calling on the Government to condemn Islamophobia. The motion was passed under heavy criticism that it was “killing free speech”, but Islamophobic-related incidents have all but stopped in Canada since.

The question that remains is what can be done to curb Islamophobia in the region?

Whilst it could be seen as inhibiting free speech, cracking down on hate speech either through the internet or restricting the distribution of Islamophobic material would be a good jumping-off point as many attain the sentiment and foster contempt towards those of the Islamic faith by consuming these hate-filled materials.

Islamophobia is a growing problem that needs to be addressed. The people of Southeast Asia should reject it in order to foster a harmonious future for ASEAN’s citizens. 14 days after the Christchurch shooting, Jacinda Ardern, New Zealand’s prime minister, gave a speech saying that “an assault on the freedom of those who want to practice their faith or religion is not welcome here”.

Related articles:

The problem with the repatriation of Rohingya refugees