The Lancang-Mekong Cooperation (LMC) marked its third anniversary last week with the announcement that China’s trade with the five Mekong member countries – Cambodia, Lao, Myanmar, Thailand and Vietnam – has reached over US$260 billion for the period, highlighting the overarching role China plays in these five countries’ economies.

A sub-regional cooperation mechanism connecting the six countries along the Mekong river, which is known as Lancang in China, the LMC was formed in March 2016 and has since seen China emerge as a willing investor and guarantor for everything ranging from agriculture to tourism as part of its wider Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

China is the largest trading partner for all the Mekong countries, and while a comprehensive list of LMC projects is not publicly available, the LMC has provided financial support for at least 132 projects in the Mekong region as of last year.

Dams playing a pivotal role

The LMC has touted connectivity and cross-border economic cooperation as its priorities, and construction of infrastructure projects such as the China-Laos Railway and the China-Thailand Railway are helping to facilitate cross-border integration and commerce.

However, among all the seemingly unchecked development that has flourished as a result of the LMC, perhaps none have had such an impact on local communities and the environment than the dams that have sprouted up across the region. Countries such as Cambodia and Lao are investing more in hydroelectric power with the help of China who then buys back the electricity at a discounted rate.

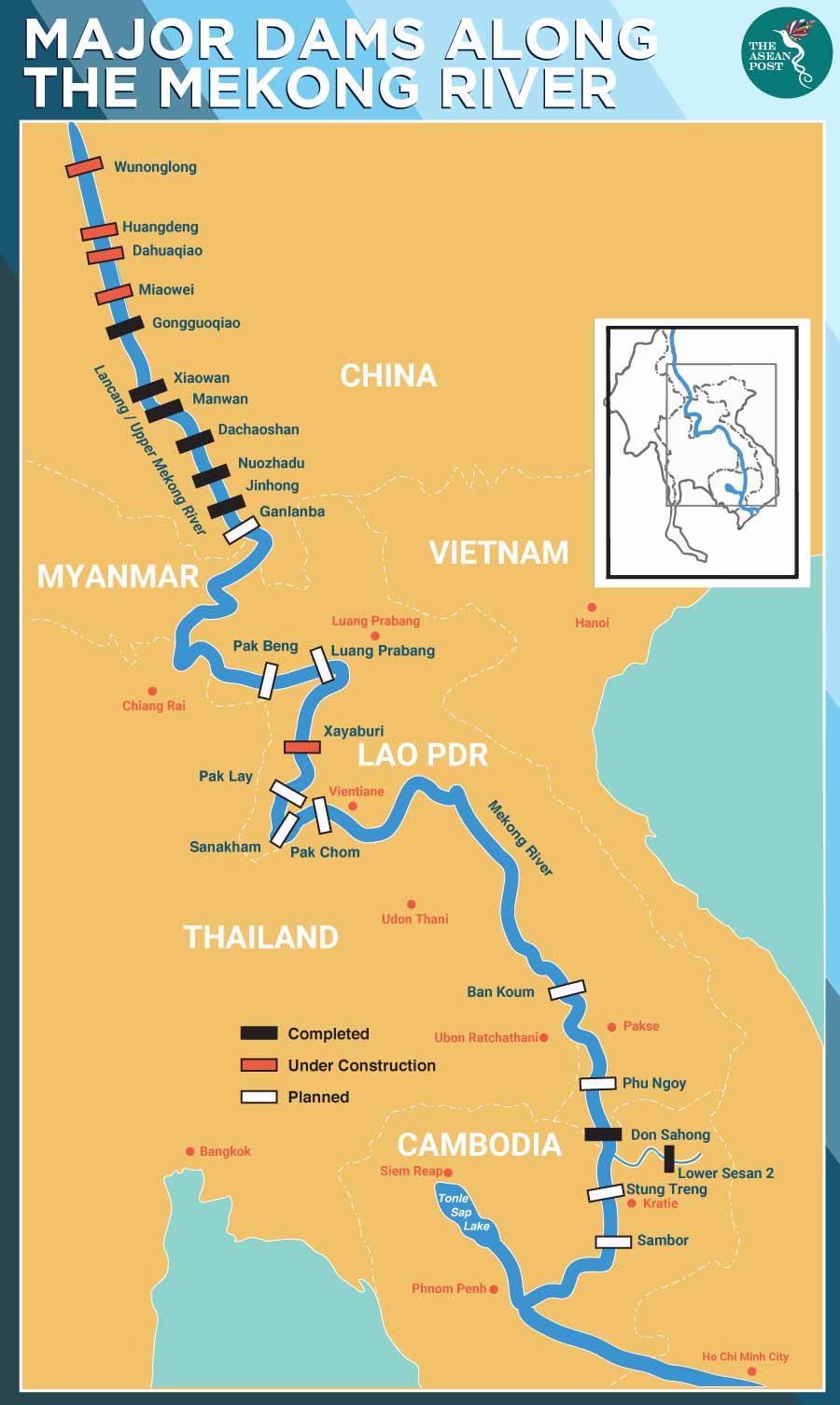

China has been building dams on the Lancang since the 1990s, with some estimates stating there are 60 dams and reservoirs now in use, 30 more under construction and 90 more under consideration. None of this is happening with consultation from its LMC counterparts, who also do not receive any significant information on the dams’ flow.

The 4,350-kilometre (km) Lancang/Mekong river flows out of China’s Yunnan province before running across Myanmar, Lao, Thailand, Cambodia and Vietnam. In effect, Chinese dams can regulate the flow of the Mekong – the lifeline for 284 million people who depend on it and its tributaries for fishing and farming as well as a water source and transportation route.

Apart from the geopolitical concerns this raises, fears over sustainable growth and environmental problems such as depleting fish stocks, river flow and soil fertility are also pressing matters for these five countries.

According to a study released by the Mekong River Commission last year, there are currently 11 proposed large hydropower dam sites on the Mekong River’s lower mainstream and 120 tributary dams that pose a threat to the ecology and economy of the region.

Unsurprisingly, none of these concerns were pointed out during last month’s week-long celebration of the anniversary which was held in all of the countries.

China even owns strategic dams along the Mekong like the Lower Sesan 2, the seventh Chinese-built dam in Cambodia, a prime example.

Chinese state-owned Hydrolancang International Energy is the majority shareholder (51 percent) in Cambodia’s largest dam, the US$800 million joint venture also involving Cambodia’s Royal Group (39 percent) and Vietnam-based EVN International (10 percent). Declared open last December, the plant will only be handed over to the Cambodian government after 40 years of operation.

The territorial sovereignty ceded by the Lower Sesan 2 project brings to mind Sri Lanka’s Hambantota port, a shining example of how high-interest BRI loans can become debt-traps. Despite misgivings about the viability of building a port in the remote southern Sri Lanka region, the country went ahead with the plan thanks to Chinese funds. However, the project soon proved to be unprofitable and Sri Lanka was forced to cede control of the port and surrounding territories on a 99-year lease after failing to fulfil its debt obligations to China in December 2017.

Perhaps realising this, Myanmar scaled back plans for a Chinese-backed port project in Kyauk Pyu from US$7.3 billion to US$1.3 billion with China looking at the passage as an alternative route for delivering oil and natural gas to the Yunnan province and bypassing the Straits of Malacca. Myanmar later said the project will be wholly financed by the private sector.

China has plans to blast certain parts of the Mekong river to allow 500-ton trade boats to pass. However, this will also facilitate the entry of security guard boats to protect these trade boats – which then runs the risk of militarising the Mekong, a river which empties into the South China Sea.

While Chinese investment is a welcome source of capital for these Mekong countries, their leaders should take a long, hard look at the many risks that they subjecting their countries to by embarking on more LMC projects which are often contained within opaque, non-binding agreements. While China pulling out of the LMC may severely reduce the number of infrastructure projects in the region, the continued unsustainable development of Chinese-backed projects along the Mekong could spell the end for many of the diverse communities that depend on this great river for survival.

Related articles:

What’s at stake for the Mekong’s fishery