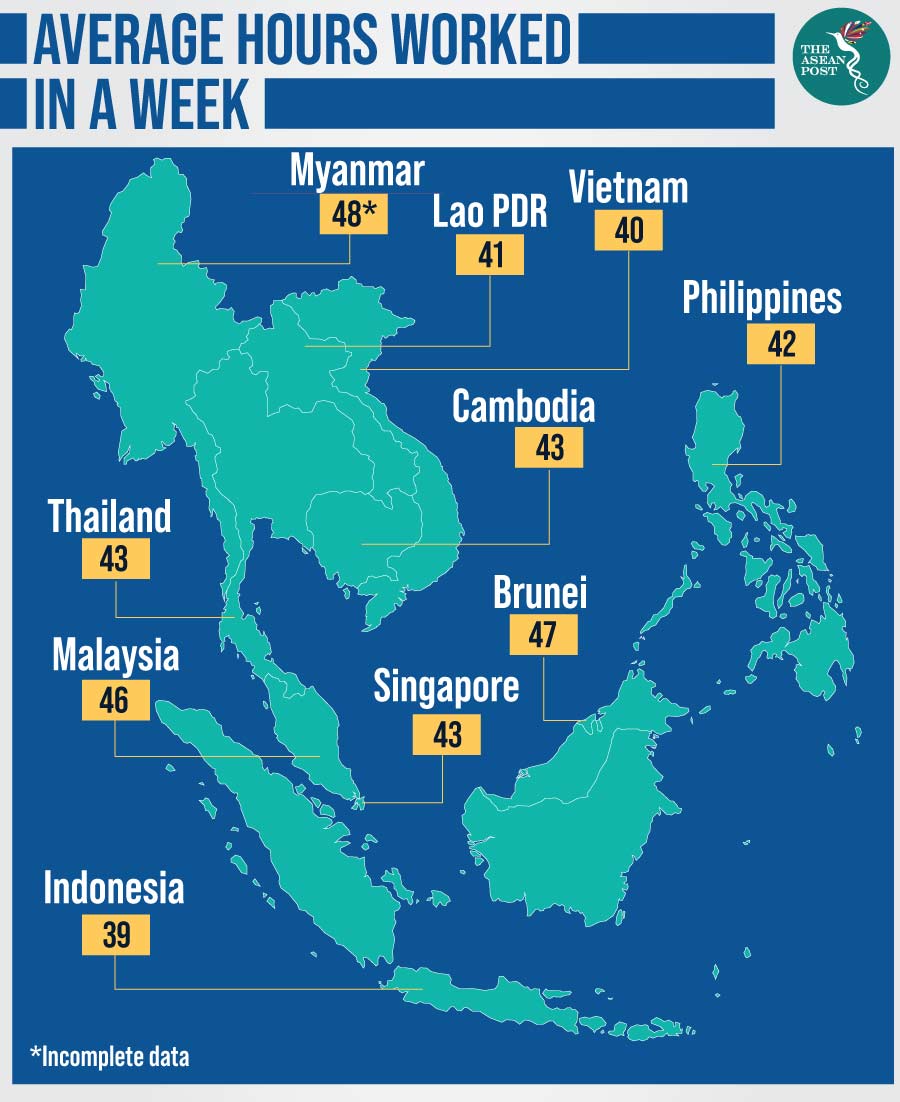

Although it is commonly accepted that productivity decreases as hours worked increases, three ASEAN countries rank in the top-10 of a list of countries where people work the most hours per week.

The top-10 countries in the list – of which nine are in Asia – all work at least 45 hours a week according to recent data by the International Labour Organisation (ILO).

Qatar leads the way with the world’s longest average working week with 49 hours, while Myanmar are joint-second with Mongolia on 48 hours. Brunei is tied with Pakistan and Bangladesh on 47 hours while in Malaysia, like China and Mexico, employees spend an average of 46 hours a week at work. Two other ASEAN countries, Thailand and Singapore, are in the top-20 with an average of 43 hours spent at work each week.

However, how productive – or more importantly, efficient – these workers are is an entirely different story.

Historic proof

The effects of long working hours on productivity, and quality of life, have long been documented.

More than a century ago, Ernst Abbe, the head of the Zeiss lens factory in Germany, observed how the shortening of working hours from nine to eight hours a day resulted in an increase in production.

Countless tests since then have shown that Abbe’s findings still hold true, and there is a point – usually at about 40-50 hours per week – after which total productive output will decrease as additional hours are worked.

In the 1920s automobile tycoon Henry Ford experimented with different work schedules for his employees. After introducing a five-day, 40-hour week in 1926, he discovered that his employees actually produced more in five days than they did in six.

Researchers from Stanford University in the United States (US) found that when employees are made to work longer than 40 to 50 hours per week, their total output over an extended period of time will drop below the level it had been when only 40- to 50-hour workweeks were required.

In other words, more work was actually shown to be detrimental to output.

As the researchers note, many managers seem to subscribe to the idea that in order to increase productive output, one need only increase the number of hours that employees work.

Taking a toll

They explain that although employees may take an hour or two at the beginning of their work day to reach maximum efficiency, after maximum efficiency is reached, a slow decline in productivity is generally seen as additional hours pass.

“In this sense it is fair to say that many managers and companies believe that hours worked and output have a linear, or at least directly proportional, relationship with one another. This is almost certainly not the case,” they pointed out.

“The troubles with crunched work environments extend beyond the immediate realm of the office. Long hours and weekends ruined by stints at the office can take a harsh toll on marriages and families, as well as employees’ general psychological and physical health,” added the Stanford University website dedicated to a project on ethics and computer science.

Apart from taking a toll at home, an overworked employee might be so fatigued that any additional work he or she might try to perform would lead to mistakes and oversights that would take longer to fix than the additional hours worked.

The Stanford researchers point out that this sort of occurrence is clear and has been long-recognised in industrial labour; overworked employees using heavy machinery are more likely to injure themselves and to damage or otherwise ruin the goods they are working on.

Quality of life

Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries featured low on the ILO list, with the Netherlands having the world’s shortest weekly working hours of 32. Other OECD countries such as Australia and New Zealand (33 hours) as well as Denmark and Norway (34 hours) also work much shorter hours.

Despite working less than their counterparts in ASEAN, the average gross domestic product (GDP) of OECD countries exceed that of ASEAN nations – except for Singapore and Brunei – pointing towards more efficient or advanced workplace processes.

The OECD realises that more hours spent at the office cuts into time spent on leisure and personal care, both which are crucial for individuals’ physical and mental well-being.

Leisure activities such as socialising and watching television, as well as personal care activities such as eating and sleeping, tend to bring more intrinsic enjoyment than activities related to paid and unpaid work state as stated in a 2011 OECD report titled ‘How's Life?: Measuring well-being’.

Furthermore, having time to rest and recuperate away from work is important for maintaining health and productivity and reducing stress.

In addition, travel to and from the workplace can significantly extend the working day and eat into leisure and family time. Commuting does not just take up time; it can also be stressful, tiring and expensive.

Can technology help?

Perhaps the answer to ASEAN’s long working hours can be found in technology.

The Fourth Industrial Revolution has been heralded for creating more efficient and productive processes, freeing up workers’ time to focus on creativity and innovation.

Automation and new technologies are increasingly replacing the need for manual labour, and consultants McKinsey & Co estimate that this trend could create 20 to 50 million jobs globally by 2030 and careers in fields such as engineering, computer science and Information Technology (IT).

Jobs which require critical and analytical thinking may not gain as much from automation or the Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT), but a general focus on efficiency instead of more working hours will ensure that each hour spent at work is productive.

Related articles:

Singaporeans are unhappy at work