A bigger representation of women in governments and positions of decision-making at all levels has been found to improve the well-being of a population through identification and targeting of lagging development agendas that impacts on their quality of life.

Southeast Asia is also not lacking with examples of strong, capable women leaders. Indonesia fields the power duo of Sri Mulyani Indrawati, its Minister of Finance and Susi Pudjiastuti, its Minister of Maritime Affairs and Fisheries. The first is credited with reducing poverty, improving living standards, boosting transparency and fighting corruption, the latter with combatting organised crime in fishery, illegal fishing and boosting fish stocks in Indonesian waters. Cambodia’s former Minister of Women and Veterans' Affairs, Mu Sochua has also been credited for her work in advancing the fight against child abuse, marital rape, sex trafficking and human trafficking in her country.

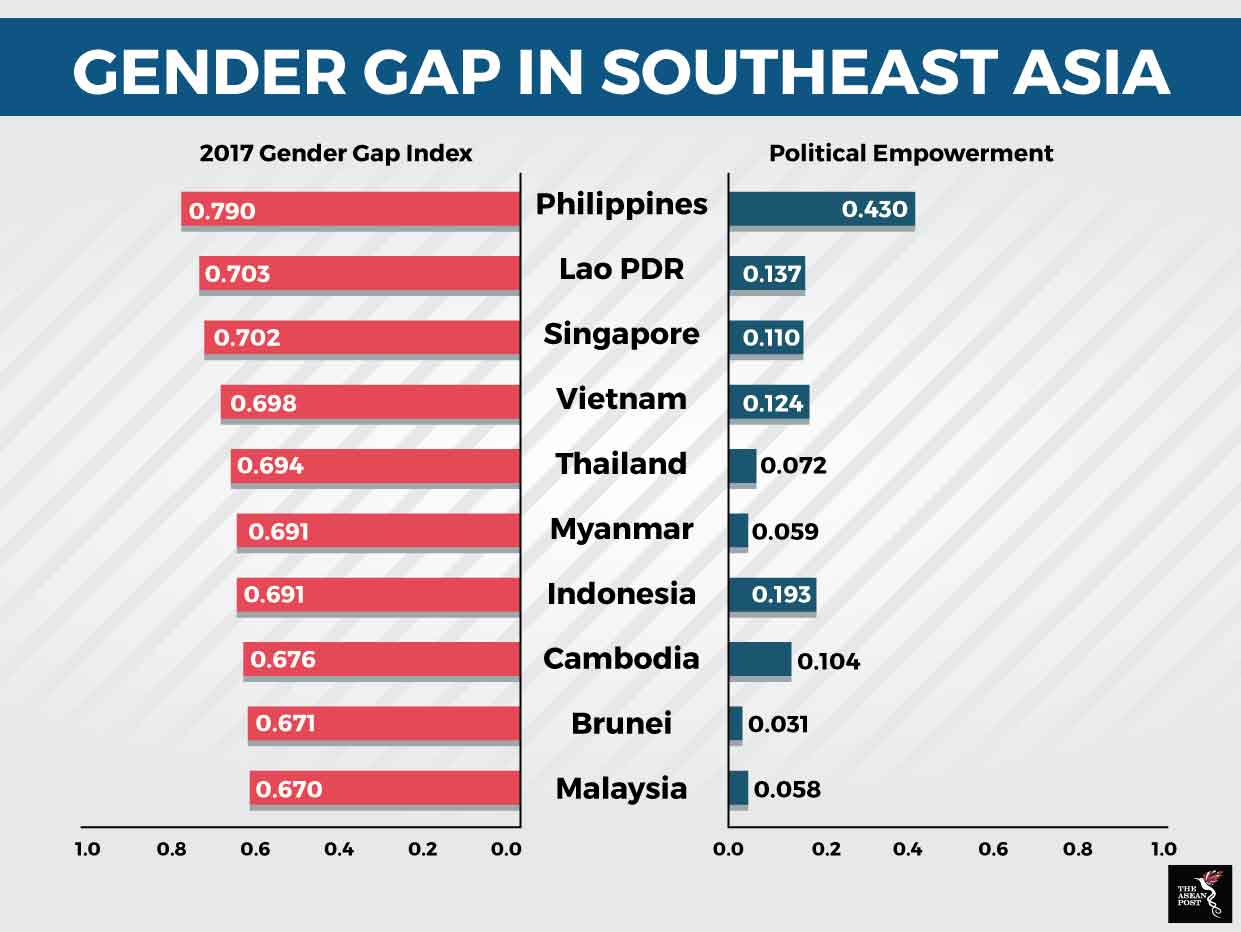

However, despite these excellent examples, the overall regional achievement in closing the gender gap including performance in political empowerment is still lagging. According to the World Economic Forum’s (WEF) 2017 Global Gender Gap Report (GGGR), the average percentage of achievement in terms of closing the gap between women and men in political empowerment in the Southeast Asian region sits at only 13 percent, compared to the 23 percent global gap. The sub-index measures gaps between male and female seats in Parliament, positions at the ministerial level and the number of years as head of state.

Only one ASEAN member country, the Philippines, managed to close more than 40 percent of its gender gap in the political empowerment sub-index at 43 percent. This – as well as its achievements in economic participation and opportunity, education attainment, and health and survival – places the Philippines in the global top 10 of countries with the smallest overall gender gap, alongside Iceland, Norway, Finland, Rwanda, Sweden, Nicaragua, Slovenia, Ireland and New Zealand.

The report also revealed four countries in the region that have only managed to close the gender gap in political empowerment by a single digit percent. Thailand achieved only a 7.2 percent gender gap closure in political empowerment, followed by Myanmar at 5.9 percent, Malaysia at 5.8 percent and Brunei at 3.1 percent.

Source: World Economic Forum.

Women mentoring women

Last year, the regional Women’s Action for Voice and Empowerment (WAVE) program, Akhaya Women and the International Women’s Development Agency (IWDA) jointly piloted the first structured women’s political mentoring program between Australia and Myanmar. Through the programme, six Myanmar women MPs across political parties at the Union level were matched with six experienced Australian female current and former parliamentarians.

According to the IWDA’s programme report, while the number of women Members of Parliament (MPs) at the national level doubled in the 2015 Myanmar election, many still face discrimination as gendered norms and stereotypes cast doubt on women’s leadership capabilities. The program aimed to support female MPs in navigating a male-dominated space through increased capacity to govern and to be influential advocates for laws and policies that promote gender equality.

According to the report, the biggest shift was observed in the mentees’ confidence to work with the men in their party. The female Myanmar MPs specifically mentioned skill development in the area of packaging key political messages, effective continuous campaigning and keeping continuous communication with their constituents.

The report stated that during the pilot program, mentors and stakeholders also noticed an increase in female MPs’ commitment to gender equality, marked by the promotion of a gender equality agenda by emphasising the importance of affirmative action within the intra-party meetings, as well as an increase in advocacy on women’s and children’s issues.

Talent is talent regardless of the gender of the person. Our inability to see beyond gender to harness the talents of women, as well as our failure in setting an environment where these talents can contribute without putting their other roles at risk, means we are losing out on critical talent needed to address emerging challenges and opportunities. When governing a population that is half women, why can’t at least half of our representatives in office be women?

Related articles: