Most of Malaysia’s largest corporations are actually controlled by an elite group of government-linked investment companies or GLICs that own major stakes in numerous large listed corporations commonly referred to as government-linked companies or GLCs. Out of the ten largest listed companies on Bursa Malaysia, eight are GLCs with a combined market capitalisation of about RM 452 billion. This does not take into account a vast number of other listed and unlisted GLCs, most notably among them Petronas, the national oil company, that dominate corporate Malaysia.

According to a study authored by Edmund Terrence Gomez, just seven GLICs have majority ownership of 35 public listed companies (PLCs), controlling about 42 percent of the market capitalisation of the entire Bursa Malaysia in 2013. Those same seven GLICs control over 68,000 companies directly or indirectly with minority interest.

In light of the GLICs’ role as trustees of sovereign wealth and the GLCs’ role as drivers of the economy in strategic industry sectors such as oil & gas, plantations, infrastructure, transport, telecommunications and financial services, their actions are closely watched for their impact and influence on the corporate landscape. To a large degree they are expected to execute the vision of their ultimate shareholder, the Ministry of Finance Inc. and set a pattern of behaviour for others to follow. Hence they are held to a higher standard than others.

This would explain why allegations of wrongdoing involving GLCs attract public interest and are widely reported. In recent times GLCs such as Sime Darby, Felda Global Ventures Holdings and 1MDB have been reported for breaching governance and behaving unethically, leading to actual arrests of senior officials for criminal breach of trust and investigations into alleged discrepancies.

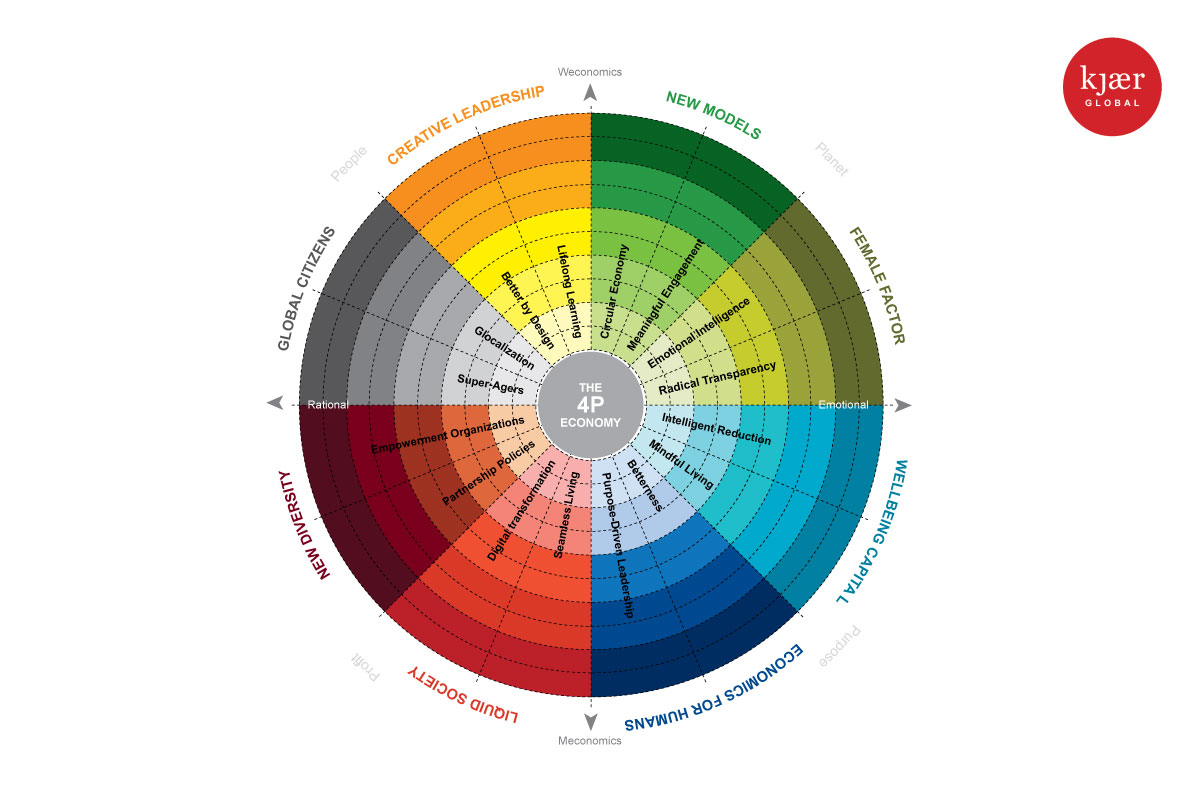

Tomorrow's leadership – a strategic review. Source: LeadWomen.

Under the World Economic Forum Global Competitive Report 2017/18 Malaysia is ranked 23rd, maintaining its position as the most competitive among the emerging economies in East Asia and the Pacific region. In contrast however, Malaysia’s position dropped one point in Transparency International's Corruption Perception Index 2016. It is now ranked 55 among 176 countries, with a score of just 49 out of 100. Good governance and transparency therefore remain key imperatives of policy makers and regulators.

The updated Malaysian Code of Corporate Governance (MCCG) launched by the Securities Commission in April introduces enhancements aimed at strengthening Malaysia’s corporate culture anchored on accountability and transparency, placing emphasis on the internalisation of corporate governance culture among listed and unlisted entities. Some of the changes introduced include those in the areas of Board Composition and Gender Diversity on Boards.

Board Composition MCCG 2017 requires at least half of the board to comprise of independent directors. However for large companies – companies on the FTSE Bursa Malaysia Top 100 Index or those with at least RM2 billion market capitalisation – more than 50 percent of board members need to be independent.

Gender Diversity The 2012 Code contained a mere recommendation for companies to establish a policy on gender diversity. The MCCG 2017 however requires companies to openly disclose their policies for appointing women to the board, as well as set targets and measures towards meeting those targets. In addition large companies are expected to appoint at least 30 percent women into their boards.

The issue of gender diversity is a major component in the Government’s Economic Transformation Program to address manpower and skills deficiencies. The female labour force participation rate increased from 46 percent in 2009 to 54.3 percent in 2016, a rise of over 700,000 more women in the workforce. At the end of 2016 Malaysia reached its target of women making up 30 percent of top management 1,446 women out of a total of 4,960 in top management, excluding CEOs. The Government wants to progress further by requiring PLCs to have 30 per cent women at board level by 2020. To stress the point, the Prime Minister personally announced that, from 2018, the Government would name and shame PLCs with no women on their boards. Gender diversity at board level is regarded with such seriousness that GLCs with no women board members might not be considered for government contract awards.

GLCs and GLICs are therefore put on notice to follow a directive declared by their ultimate owner, the Ministry of Finance Inc. (headed by the PM) and those which are listed must also abide by the MCCG 2017. Complying would be far less costly than losing the opportunity of procuring government contracts.

Approximately RM260 billion was set aside for development expenditure under the 11th Malaysia Plan. GLCs eyeing to participate in a slice of the action in that enormous pie would do well to heed the PM’s call; they would have nothing to lose and everything to gain.

The challenge for GLCs is to search for the top notch women talents to join their boards.

Shahjanaz is a lawyer by training who harboured aspirations of becoming a writer. She finally took the plunge in 2012, and has been an independent writer/editor ever since. Although her life as an ambassador's daughter led her to grow up and be educated overseas, she adores Malaysia, and in particular Kuala Lumpur, her birth place, warts and all.

This article is a collaboration between The ASEAN Post and LeadWomen. The views and opinions expressed above are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of The ASEAN Post.