E-cigarettes and vaping devices (EVC) have dominated the public and academic debate on tobacco control since its introduction into the market. Now, Malaysia is looking to introduce stricter regulations on the sale and use of EVC, placing it together with tobacco products under a single law that would prohibit promotions and advertising, usage in public areas and use by minors.

E-cigarettes and vapes are different. An e-cigarette is usually shaped like a pen and filled with nicotine, while vapes are handheld devices that may not have nicotine in its e-juice or oil. In Malaysia, a ban on vaporiser liquids containing nicotine has been in place since November 2015.

Smokers are youth

There is a rising uptake of EVC among Malaysia’s youth. Due to this, the Health Ministry there is not discounting a total ban on the products. “Everything is currently in the planning stage. We are examining whether to fully implement the ban on vape use, like some other countries,” said Deputy Health Minister, Dr Lee Boon Chye.

Research in the Journal of Community Health by Li Ping Wong et al. in 2016 revealed that 39 percent of e-cigarette smokers are youths in universities while 36 percent are young professionals. Their main reason for using EVC is to quit the smoking of tobacco.

The research identified other reasons students have for smoking e-cigarettes and vaping such as their perception that e-cigarettes are not as intrusive as tobacco cigarettes and can be used in public places and the notion that e-cigarettes are safer than smoking tobacco.

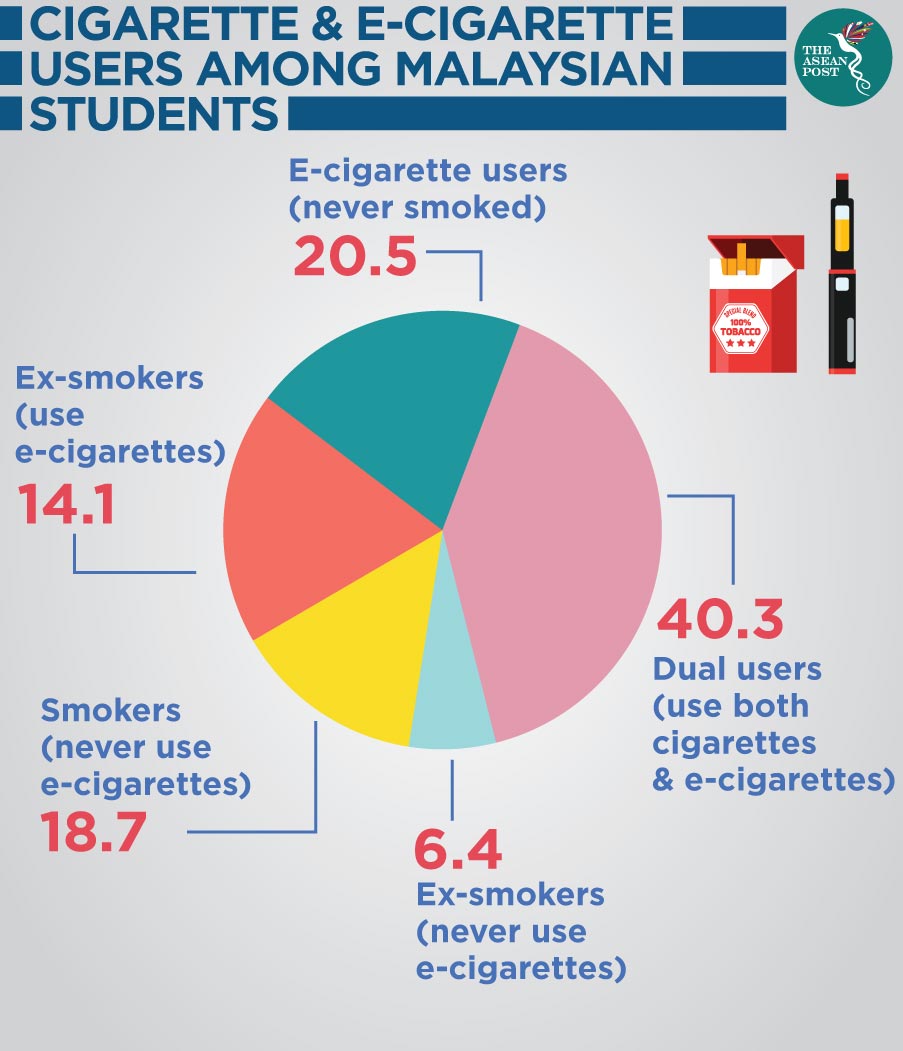

However, based on 2018 research by Sharifa Ezat Wan Puteh et. al. on ‘‘The use of e-cigarettes among university students in Malaysia,’’ in the Tobacco Induced Diseases Journal, the number of youths who use e-cigarettes as a tool to quit is 14.1 percent, which is lower than current EVC smokers who have never smoked a cigarette (20.4 percent). There is also a high percentage of youths who are dual users (smoking both, tobacco products and EVC) at 40.3 percent.

Malaysia’s Ministry of Health also conducted a study in 2016 – the Tobacco and E-Cigarette Survey Among Adolescents in Malaysia (TECMA) – and found that 300,000 schoolchildren between the ages of 10 and 19 were using electronic cigarettes and vapes; a majority of whom have never smoked a cigarette before. In many cases, youths are using EVC unwittingly, sharing it among friends and without parents’ knowledge.

Vaping’s health concerns

The practice of smoking EVC should not be taken as harmless as ongoing research is being conducted on its long-term health effects and connection to the risk of diseases. Among the known health effects of smoking EVC so far include dry mouth, dizziness, coughing, vomiting, nausea, headaches, blurred vision and abdominal pain.

The United States (US) authorities recently reported 29 deaths and 1,299 cases of respiratory illnesses linked to the use of EVC.

The Penang Consumers Association (CAP) has also called for a total ban on the sale and use of EVC. “A 2017 study conducted in Malaysia revealed that 54 percent of vapers obtained their zero-nicotine e-liquid from the black market and 30 percent obtained homemade e-liquid,” its President, Mohideen Abdul Kader said.

In August 2019, the Health Ministry confiscated 66,998 bottles of e-juice worth RM1.4 million (US$334,000), from 78 premises, selling nicotine tainted e-juice to school-going children. To reduce risks to their health, people who use EVC should purchase products from reputable manufacturers.

Yet, potentially harmful chemicals have been found in the vapour from commercially produced nicotine vaping products. These include metals, acrolein and formaldehyde, although the same chemicals are found in much higher levels in cigarette smoke, along with more than 5,000 other chemicals, including many carcinogens.

A 2018 study by William Stephens in the Tobacco Control Journal, when comparing the harmful chemicals in nicotine vapour and cigarette smoke estimated that the lifetime cancer risk from smoking was 250 times that of vaping.

Other than EVC’s harmful effects on human health, Malaysia’s Health Ministry also stated that the use of EVC is still not proven to be an effective modality to quit smoking. Last year, the CAP revealed that Malaysian smokers had smoked through 11,588.7 million sticks of cigarettes in 2017 alone, which is equivalent to RM9.9 billion (US$2.4 billion). The Health Ministry stated that by 2025, it would cost the government RM7.4 billion (US$1.8 billion) to treat smoking-related diseases.

The World Health Organisation (WHO) also estimated that more than 20,000 male adults in Malaysia die every year from complications due to a smoking habit.

For some, the ban on e-cigarettes denies smokers the right to use a less harmful form of nicotine, while allowing the most toxic, tobacco cigarettes, to be freely sold is an incoherent form of risk regulation. It also disadvantages smokers who may have difficulty quitting but want to reduce the risks of smoking.

“The government is being unfair to former smokers looking for better cessation devices. We all know that this is for the interests of tobacco lobbyists, so the government isn’t fooling anyone,” said Abdul Hakim Abu Bakar, who is an EVC user.

According to Euromonitor International, the global market for e-cigarettes was worth US$15.7 billion in 2018, with a projection to double to US$40 billion in 2023. On the other hand, the global cigarette market was worth US$888 billion in 2018 and is projected to reach a value of US$1,124 billion by 2024. Debates on e-cigarettes can be seen as a huge distraction if less attention is paid to the more deadly tobacco industry.

In Malaysia, more than 5,000 enterprises, including 1,800 vape shop owners, will be impacted once the government enforces the new law to regulate the use and sale of EVC in the country. Whether this step will reduce the number of EVC users among the country’s youth remains to be seen.

Related articles:

Malaysia gets tough on smokers