The Malaysian government should take a long, hard look at the mirror and ask itself if the country really is the world champion of conquering poverty.

The United Nations (UN) Special Rapporteur on extreme poverty and human rights, Philip Alston, spent 11 days in Malaysia meeting state and federal government officials, international agencies, civil society, academics and people affected by poverty in urban and rural areas this month.

His travels through five states saw him visit a soup kitchen, a women’s shelter, a children’s crisis centre, low-cost housing flats, a disability centre, indigenous communities, informal settlements and schools – after which he said that Malaysia’s claim that only 25,000 households, or a rate of 0.4 percent, would make it the “world champion for conquering poverty”.

If the government’s figures are to be believed – from 49 percent in 1970 to just 0.4 percent in 2016 – Malaysia would have the world’s lowest national poverty rate, a feat they could only have achieved by using an outdated and unduly low poverty line that does not reflect the cost of living and by excluding vulnerable populations from its official figures.

Tragic, ridiculous

A professor of law at New York University, Alston also called the national poverty line of RM980 (US$233) per household per month as “tragically low” and “ridiculous” since an urban family of four would have to survive on RM8, or less than US$2, per person per day.

Malaysia’s poverty classification is the same used for low-income economies, or US$1.90. Low-income economies are defined by the World Bank as those with a Gross National Income (GNI) per capita of US$1,025 or less in 2018.

The World Bank classifies Malaysia as an upper middle-income economy, and with a GNI per capita between US$3,996 and US$12,375, its poverty line would have to be US$5.50 (RM23).

“This is a tragically low line for a country on the cusp of attaining high income status, especially since a range of rigorous independent analyses have suggested a more realistic poverty rate of 16-20 percent, and about nine percent of households survive on less than RM2,000 (US$479) per month,” Alston said.

Disappointed minister

While Alston’s findings may not have been shocking, the response from Economic Affairs Minister Mohamed Azmin Ali certainly was.

Instead of calling for a fact-finding mission of his own, the “disappointed” minister instead flat-out denied Alston’s assessment and told local media that the UN expert’s claim that many Malaysians have a hard time securing access to food, shelter, education, and healthcare as “misconceived, erroneous and clearly lack empirical evidence and rigorous scientific analysis”.

“We stand by our absolute poverty rate which stands at 0.4 percent of total households…,” he told local media, adding that the country’s poverty rate is derived from internationally accepted standards based on the Canberra Group Handbook on Household Income Statistics, Second Edition (2011), which was published by the UN.

Even more surprising is the fact that the government’s review of the 11th Malaysia Plan 2016-2020 last October – conducted by none other than the Ministry of Economic Affairs – noted that “the current poverty line income (PLI) model will be reviewed to be more reflective of the current consumption pattern as well as needs and demography of households.”

Although Prime Minister Dr Mahathir Mohamad has said the government would study Alston’s findings, the damage has already been done.

The knee-jerk, defensive response by Azmin – the Economic Affairs Minister no less – showed just how out of touch he is with the reality on the ground, his unwillingness to have a rational discussion about the issue, and his ignorance in using an eight-year-old handbook as a benchmark without noting that the cost of living would have inevitably risen since then.

The Ministry of Finance, which states in its 2019 Economic Outlook that the incidence of hardcore poverty has been at zero percent since 2014 in both rural and urban areas, might also want to take another look at their numbers.

Nothing new

The Malaysian Trades Union Congress (MTUC) and the National Patriots Association both voiced their displeasure with Azmin’s comments, with the MTUC pointing out that Alston’s findings were in line with the congress’ view that poverty isn’t being assessed properly in the country and that “around five million workers are earning below the poverty line.”

Economist Martin Ravallion, who holds the Edmond D. Villani Chair of Economics at Georgetown University and is the current visiting chair for the Ungku Aziz Centre for Development Studies at Universiti Malaya, found that Malaysia’s poverty line would include around 20 percent of the population of 33 million people when compared with countries with a similar average income.

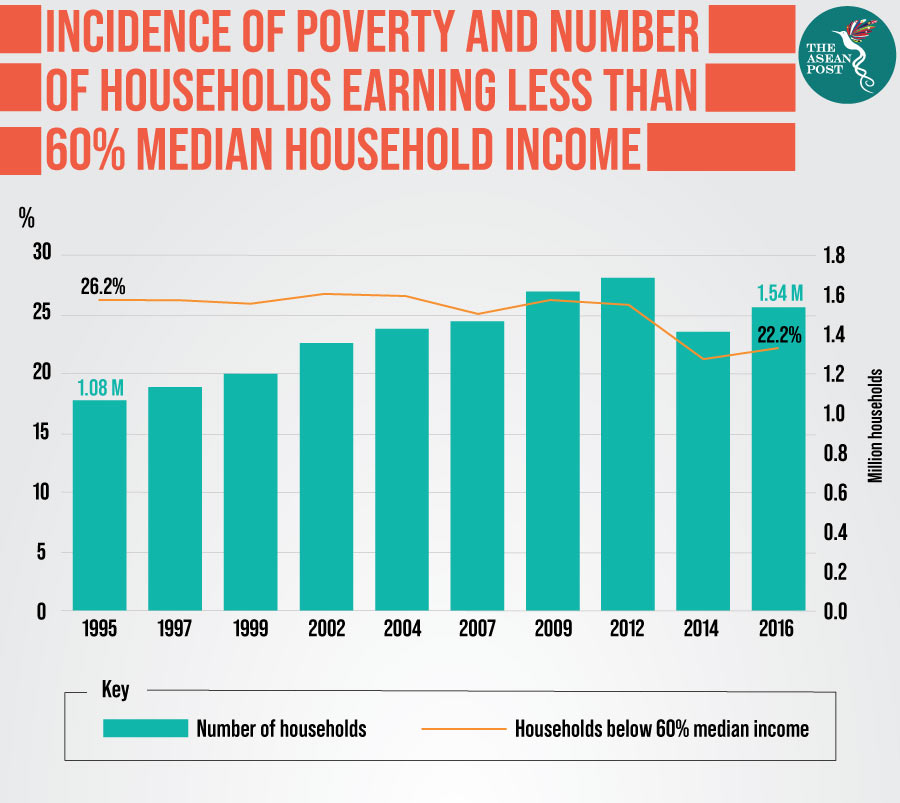

Malaysian think tank Khazanah Research Institute, which states that Malaysians feel a sense of disconnect with official poverty statistics, found that a relative poverty measure of 60 percent of median income would show 22.2 percent of households living in poverty as of 2016.

Meanwhile, UNICEF (United Nations Children's Fund) reported this year that a relative poverty measure similar to that adopted by most OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) countries would mean around 16 percent of Malaysia’s population lives in poverty.

Crucially, the government should stop withholding key information to understanding poverty and inequality, such as household survey microdata, as widely reported by researchers including Alston.

With even Malaysia’s newly elected king, Sultan Abdullah Ri'ayatuddin Al-Mustafa Billah Shah, using his coronation speech last month to warn that “the cycle of the legacy of poverty should be addressed immediately,” at the cost of nation building, it is high time the government stops living in denial and starts spending more time on the ground with the people they claim to represent.

Related articles:

Food security is key to SDGs success