The teaching and learning of science and mathematics in English (PPSMI) was a government policy implemented in 2003. It was designed to help improve the command of the English language among students by implementing it in the teaching and learning of science and mathematics. It was unfortunately considered a failure by many following a 2007 study by the International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement’s (IEA) International Study Centre entitled “Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study” (TIMSS). The study revealed that Malaysia’s average score in mathematics had dropped to 474 in 2007 from 508 in 2003. Many observers attributed this drop to the use of the English language in teaching and learning mathematics.

The PPSMI was promptly abolished in 2012 and subsequently replaced by the Dual Language Programme (DLP). Where PPSMI necessitated the use of English, the DLP allows schools to choose if they want English to be used as the medium for teaching and learning mathematics and science. However, this created further disparity in the job market as those proficient in English are much more employable than those who are not, said Malaysia’s prime minister Dr Mahathir Mohamad in an interview with a local daily recently.

Dr Mahathir Mohamad had expressed his intentions of reintroducing the system last year while on the campaign trail for the country’s 14th general election. He has yet to reimplement the PPSMI but the mere idea of it has received both, support and resistance from both sides of the aisle. Prof. Dr Teo Kok Seong, Principal Research Fellow at the Institute of Ethnic Studies (KITA), National University of Malaysia (UKM), said back in 2016 that the PPSMI was “outdated” and the DLP more “democratic” due to the latter’s flexibility in allowing schools to choose their own language as medium of instruction. A reintroduction of the PPSMI could have serious repercussions across Malaysia’s education system.

Hurdles to overcome

For instance, teachers could struggle with the idea of teaching in a language that they are not fluent in and may use “shortcuts” when teaching. In 2012, a study by the Faculty of Social Sciences and Humanities, National University of Malaysia (UKM), entitled “Exploring English Language Learning and Teaching in Malaysia” showed that the teaching process in English involved “rote-learning” techniques as opposed to actual comprehension.

This is especially concerning as science and mathematics are subjects that need to be comprehended. Dr Mahathir Mohamad said in 2019 that Malaysians could help advance their knowledge with the proper comprehension of science and mathematics.

If the PPSMI is implemented, many teachers would have to grapple with the prospect of teaching science and mathematics in a language they themselves may not have mastered as yet.

However, students should also be able and willing to comprehend what is being taught to them. A paper by the Sultan Idris Education University’s Faculty of Management and Economics in April 2017 outlined the reasons why the PPSMI initiative failed. One of the factors was a lack of English proficiency among students. This could be due to the medium of communication at home or the lack of desire to be fluent in English. As a result, students were uninterested in subjects that were taught in “advanced” English, particularly mathematics and science.

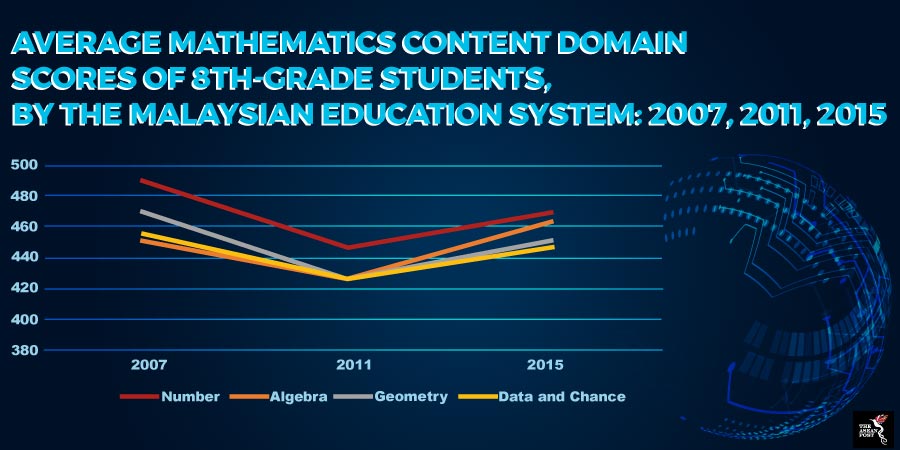

While many educationists still feel language plays an important role in mastering mathematics and science, the statistics say otherwise. The TIMSS shows that Malaysians on average scored 474 for mathematics in 2007 but only 465 in 2015. Although this is a marked improvement from 2011’s score of 440, it is still not a clear indication that by not teaching mathematics and science in English, students are performing just as well as previous generations.

Significance of English

The sad reality is that mastering the English language could help young Malaysians in the job market immensely. Over 90 percent of companies believe that Malaysia’s fresh graduates are sorely lacking in English proficiency, according to the Malaysian Employer’s Federation (MEF). This shows that English fluency is relevant regardless of the system used to teach students in school or the qualification they pursue later on at University.

The immediate desire to make English compulsory as part of the teaching and learning process for mathematics and science in schools may be a little premature. Instead, Malaysia’s Ministry of Education should focus on ensuring teachers are properly trained in the skills necessary to incorporate English effectively in their teaching methods. Students too need to work harder at improving their English language skills. Only then can Malaysia’s youth be moulded into a workforce capable of competing on the regional (and global) stage as ASEAN marches towards the Fourth Industrial Revolution.

Related articles:

The Doctor is back. Can Malaysia be cured?