Recent news reports in Thailand have revealed that teacher-education graduates will not be required to have a strong grasp of the English language.

"We have reached this resolution because most stakeholders at a forum on the draft Thailand Qualifications Framework (TQF) disagreed with the plan to be too ambitious when it comes to the graduates’ English,” said Rathakorn Kidkan, chairman for the committee in charge of preparing a teacher qualifications framework.

“There were serious concerns that students may not be able to graduate if the English mastery requirement was set too high,” he explained.

Rathakorn also chairs the Council of Rajabhat University’s Education Deans.

This follows the initial proposal that the TQF require teacher-education graduates who have not majored in English to attain a B2 level in English under the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR). The CEFR is an international standard for describing language ability using a six-point scale from A1 for beginners, up to C2 for those who have mastered a language. Those majoring in English would have been expected to reach the C1 level.

The need for English

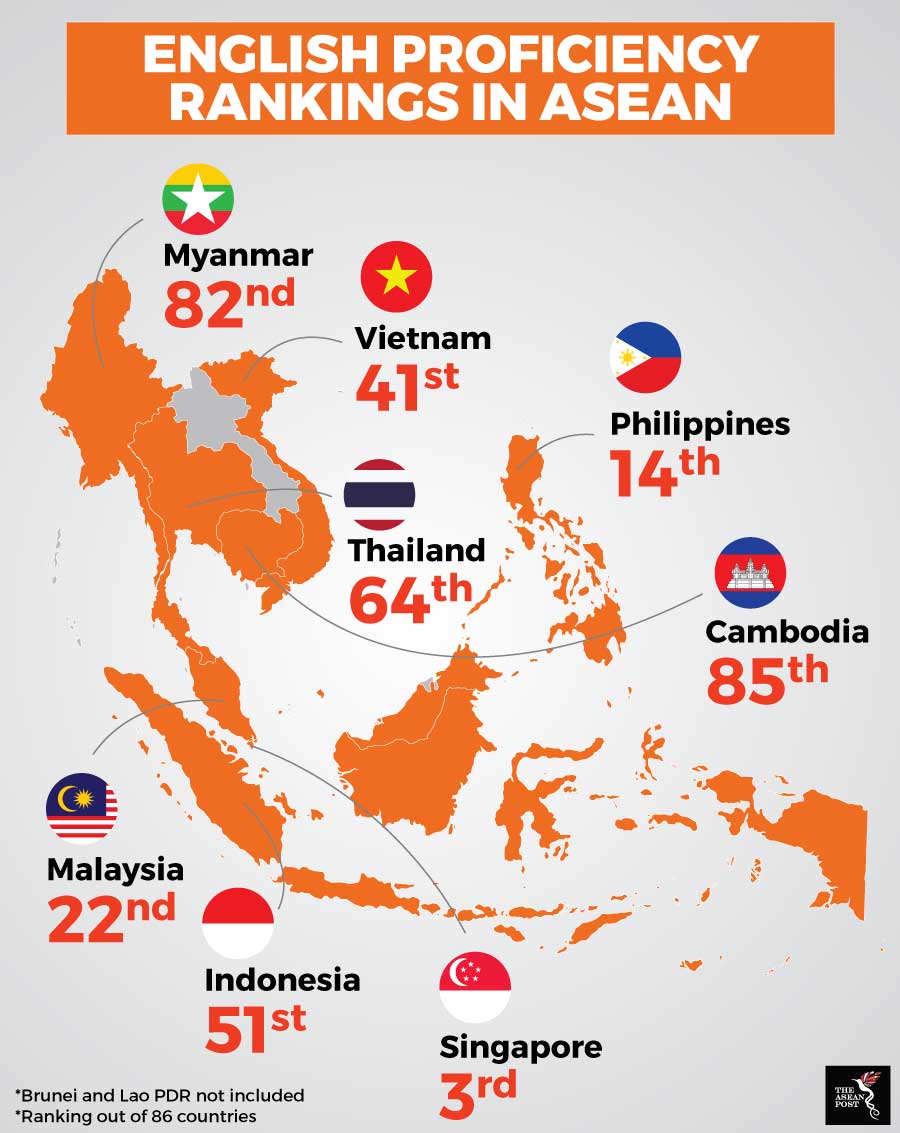

The Education First (EF) 2018 English Proficiency Index does not paint a very good picture for most ASEAN countries with the exception of Singapore which holds third place in a study that includes 86 countries. In comparison, the Philippines was in 14th place, Malaysia in 22nd, Vietnam in 41st, Indonesia in 51st, Thailand in 64th, Myanmar 82nd, and Cambodia in 85th. Brunei and Lao were not included in the study.

Source: Education First

Source: Education First

Among ASEAN nations, Thailand, in particular, has often expressed concern regarding its lack of proficiency in English. In 2016 – when the country was placed 62nd out of 70 countries on EF’s 2015 English Proficiency Index – the education ministry there acknowledged that its low ranking posed problems for Thailand as it seeks to achieve greater integration within the ASEAN community and aims to increase business, social, cultural and employment opportunities among Southeast Asian countries.

Thai officials expressed concern that Southeast Asian nations like the Philippines, Malaysia, Singapore and Myanmar, which have better English language education, would have an edge when it comes to doing international business.

Aside from international business, the tourism industry – which is a significant contributor to Thailand’s economy - may also face challenges. This was concurred by Alexander Franco, Director of the Centre for International Business and Education Research in Yangon, Myanmar, and Scott Roach, senior lecturer at Stamford International University in Bangkok. They pointed out that “the importance of English as a lingua franca is, of course, important to tourism which now makes up about 12 percent of the Thai economy.”

According to the country’s Tourism and Sports Ministry, tourism contributed 17.7 percent to Thailand’s gross domestic product (GDP) in 2016 and 16.7 percent in 2015. Meanwhile, the World Travel and Tourism Council says tourism accounted for 10.4 percent of global GDP and 313 million jobs, or 9.9 percent of total employment in 2017.

What Thailand wants

When talking about tourism, especially in Southeast Asia, the matter of Chinese tourists stands out. The question then would be why should Thailand focus more attention on English as opposed to Mandarin or Cantonese. That’s a viable option even when considering international business, after all, Mandarin is also considered an international language today.

It is, however, Thailand that needs to decide what it really wants. So far, Thailand has often expressed its intention to improve its nation’s English proficiency. Education minister Teerakiat Jareonsettasin, for example, has consistently expressed his intention to improve the standard of English even while he was the deputy minister of education in 2016.

During that year, he unveiled a plan that called for drastic changes to the English language curriculum in schools, including more classes, new textbooks and an intensive training programme for top teachers who in turn would become “master trainers” for other teachers.

More recently, he was reported as pointing out that the country does not currently have an official assessment system for speaking and writing English in schools, and lacks the native speakers needed to conduct these assessments.

“When you examine speaking and writing, usually you would need native speakers. You cannot have native speakers assessing 10 million students,” he said referring to a survey by the ministry which revealed that only six Thai English-language teachers out of more than 43,000 in public schools across the country have native-like fluency.

If Thailand does indeed intend to be more fluent in English then it is important that it starts with its teachers. Allowing teachers with poor English language skills to graduate will only create a ripple effect in the education system which will unfortunately negate the country’s desire to improve its English proficiency.

Related articles:

Thailand’s Chinese tourist dilemma