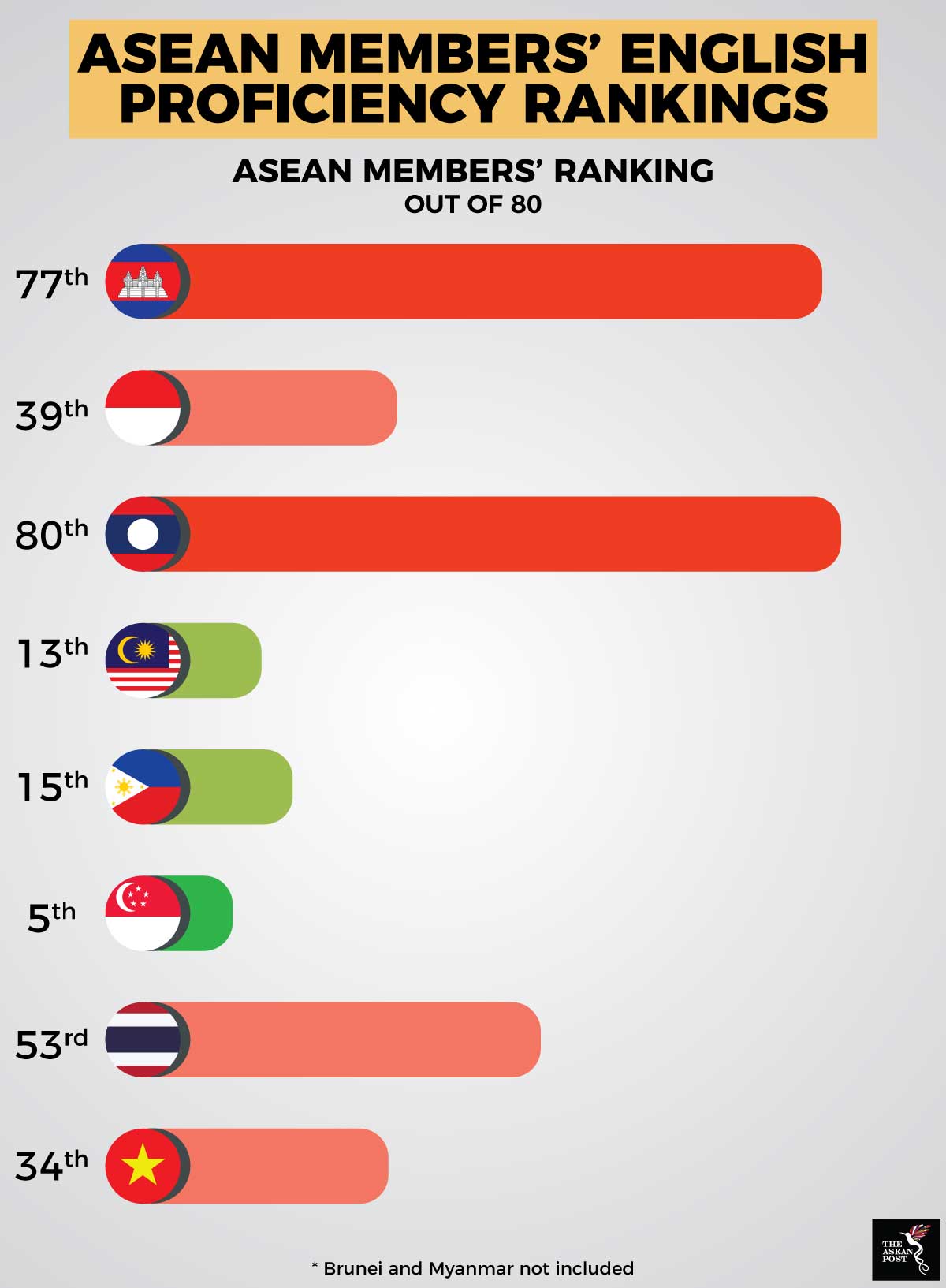

The Education First (EF) 2017 English Proficiency Index does not paint a very good picture for most ASEAN countries with the exception of Singapore which holds fifth place in a study that includes 80 countries. In comparison, Malaysia comes next in 13th place, Philippines in 15th, Vietnam in 34th, Indonesia in 39th, Thailand in 53rd, Cambodia in 77th and Lao PDR in 80th. Brunei and Myanmar were not included in the study.

Thailand, in particular, has expressed concern regarding its lack of proficiency in English. In 2016 - when the country was placed 62nd out of 70 countries on EF’s 2015 English Proficiency Index - the education ministry there acknowledged that its low ranking posed problems for Thailand as it seeks to achieve greater integration within the ASEAN community and aims to increase business, social, cultural and employment opportunities among Southeast Asian countries.

Thai officials expressed worry that Southeast Asian nations like the Philippines, Malaysia, Singapore and Myanmar, which have better English language education, would have an edge when it comes to doing international business.

Andrea Benešováa and Jiří Tupaa from the Department of Technologies and Measurement at the University of West Bohemia in the Czech Republic published a study in 2017 stating the importance of English in Industry 4.0.

The Requirements for Education and Qualification of People in Industry 4.0 study found that top jobs including Informatics specialists, PLC programmers, Robot programmers, Software engineers, Data analysts, and cybersecurity personnel will all require proficiency in English.

Source: Education First

Push for better English

Thailand’s education minister Teerakiat Jareonsettasin has consistently been highlighting his intention to improve the standard of English even while he was the deputy minister of education in 2016. During that year, he unveiled a plan that called for drastic changes to the English language curriculum in schools, including more classes, new textbooks and an intensive training programme for top teachers who in turn would become “master trainers” for other teachers.

More recently, he was reported as pointing out that the country does not currently have an official assessment for English speaking and writing in schools, and lacks the native speakers needed to conduct these assessments.

“When you examine speaking and writing, usually you would need native speakers. You cannot have native speakers assessing 10 million students,” he said referring to a survey by the ministry which revealed that only six Thai English-language teachers out of more than 43,000 in public schools across the country have native-like fluency.

Better money, better schools

But the ones suffering most from a lack of quality education – and in effect lower English proficiency – are those unable to afford good quality education in Thailand where education inequality is still rampant.

Bangkok’s Shrewsbury International School principal Stephen Holroyd found that elite schools continue to send their most affluent students to expensive Oxbridge and Ivy League universities in the United Kingdom (UK) and the United States (US). These internationally educated students are better positioned to get the top jobs in Thailand not only because of the quality education they received but also by networking with other elite foreign university students in Thailand.

Thailand 4.0

In 2016, the military government unveiled its newest economic initiative dubbed “Thailand 4.0”. The initiative was a master plan to get the country Industry 4.0-ready and with the ultimate aim of freeing Thailand from the middle-income trap by making it a high-income nation in five years since its inception.

In keeping with that trend, Teerakiat revealed that the education ministry is working with the British Council and Chulalongkorn University’s Computer Engineering Department to develop Artificial Intelligence (AI) capable of evaluating students’ speaking and writing skills online. This is an effort to address the lack of native speakers needed to conduct English assessments.

In the meantime, Thailand launched a free mobile app – Echo English – in 2016 that encourages people to practice conversational English through games. It hopes that the app will help improve Thais’ English proficiency, and in turn their global competitiveness. The Ministry is currently developing different versions of the app for students and for specific professions.

The free app includes 40 online English lessons and is presented as a multiple-choice quiz game where users can compete against one another.

It is likely that Thailand will yield positive results if it continues its push towards ensuring its people have a better command of the English language. The education ministry has also shown that it isn’t afraid to employ innovative ways to achieve this. However, the challenge for Thailand is to ensure that all its people improve their English proficiency and not just an elite few.

Related articles:

Education in the Age of Automation