The COVID-19 pandemic continues its rage across the globe, killing some 2.5 million people to date and infecting 113 million since it started a little over a year ago. It has negatively affected livelihoods, businesses and the economy in general, and ASEAN member state Malaysia is not an exception.

Malaysia’s economy declined further in the fourth quarter of 2020, leading to a worse contraction in Gross Domestic Product (GDP) than initially expected by the ruling government, as reported by local media in the country.

Malaysia’s fourth-quarter GDP fell by 3.2 percent, more than the 2.7 percent decline in the third quarter of 2020. Overall, its GDP shrank by 5.6 percent, the biggest contraction since the 1998 Asian Financial Crisis.

However, Zafrul Abdul Aziz, Malaysia’s Finance Minister said yesterday that the country’s economic recovery plan is on the right track as the National COVID-19 Immunisation Program – the largest jab programme Malaysia has ever conducted – begins. He added that economic recovery would follow with the recovery in public health.

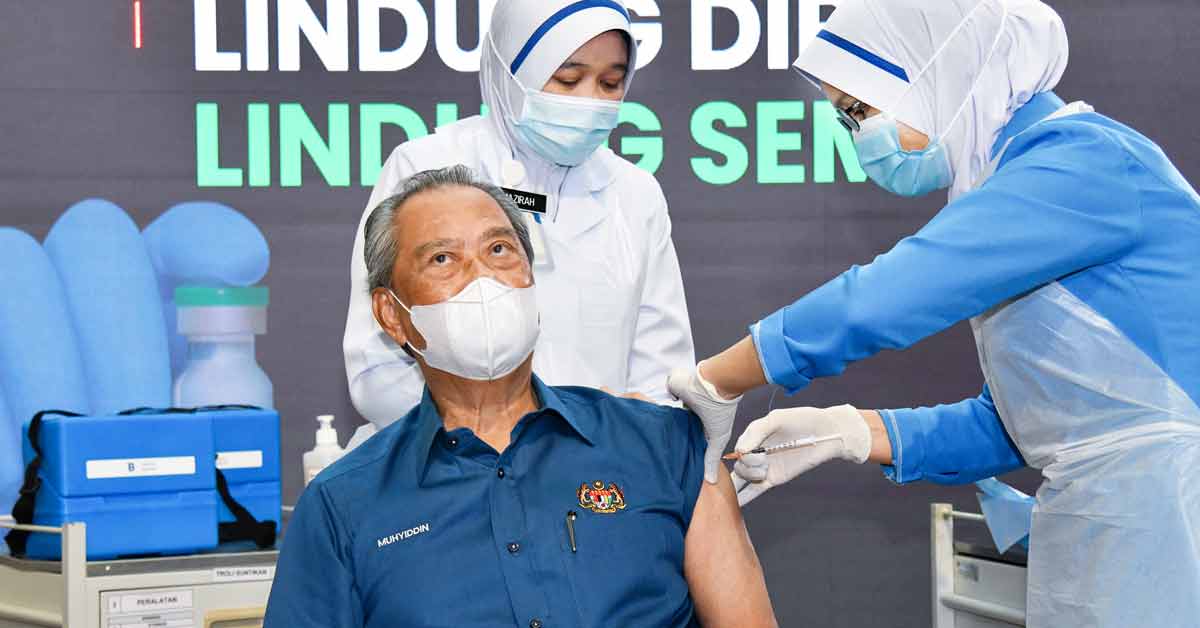

Prime Minister Muhyiddin Yassin was the first person to receive the COVID-19 vaccine in Malaysia. Also joining the Premier in getting their first jab of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine were Health Director-General Noor Hisham Abdullah and four other front-liners.

This comes following criticism from observers about the speed of Malaysia’s vaccine procurement process, compared to its closest neighbours, Singapore and Indonesia which kicked off their vaccination programmes much earlier.

But Khairy Jamaluddin, Minister of Science, Technology and Innovation, also the Coordinating Minister for the vaccination programme defended the government’s perceived slowness in his blog post back in mid-January that “Malaysia is on track to receive our first delivery before the end of February. This timeline was agreed to when we negotiated our contract with Pfizer in November 2020. This will still place us among the fastest in the Asia Pacific to access COVID-19 vaccines.”

In the post, he also wrote about the delivery schedule and addressed concerns that compared Malaysia to the two aforementioned neighbours.

“Malaysia is not slow in receiving vaccines. Yes, we are not among the first. Many developed countries have received their vaccines. This is because they have paid a lot to corner the market even before the availability of safety and efficacy data. But we are certainly not laggards,” he said.

Third Wave

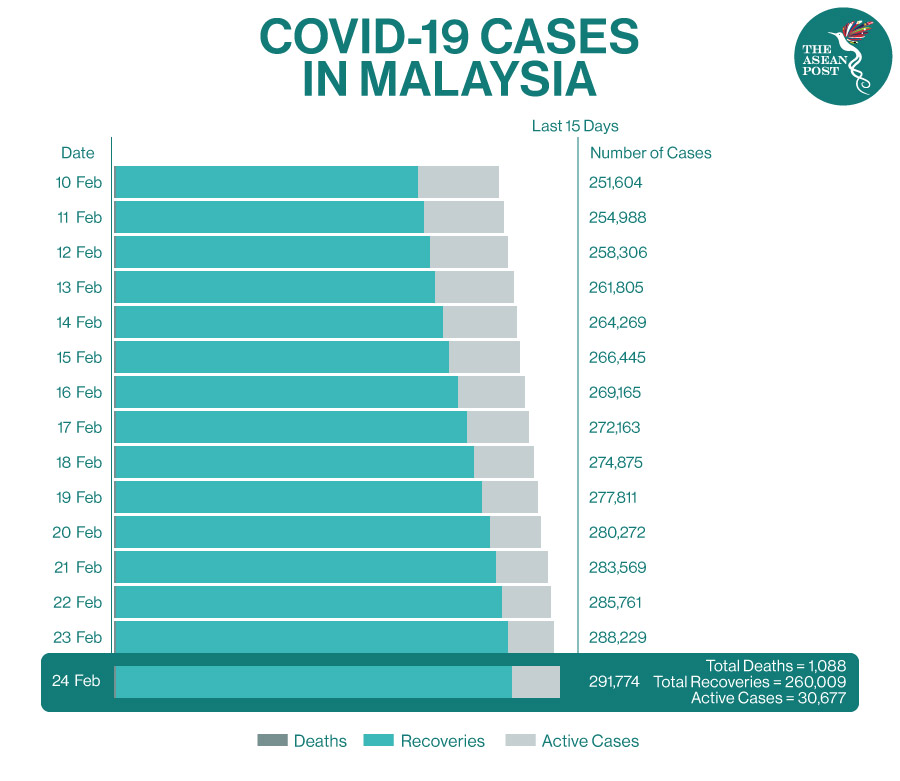

At the time of writing, Malaysia has reported 291,774 COVID-19 cases. It entered the third wave of the coronavirus pandemic in October 2020, just after it had eased coronavirus restrictions.

In recent months, Malaysia has been reporting a four-digit daily tally consistently, and Muhyiddin even warned in January that the country’s “healthcare system is at breaking point” and that “the situation today is indeed very alarming.”

The country was doing well during the first partial lockdown, known locally as the Movement Control Order (MCO). The order was originally to be in effect from 18 March to 31 March, 2020 but was extended four times with additional two-week “phases” over the course of two months.

As the situation gradually improved, the government then announced a relaxation of COVID-19 measures, which came in the form of a Conditional Movement Control Order (CMCO).

On 7 June, the Prime Minister announced that the CMCO would end on 9 June, with the country moving into a post-lockdown recovery phase, the Recovery Movement Control Order (RMCO) for the rest of 2020.

Throughout the coronavirus pandemic, since it was discovered in Malaysia a year ago, the country has encountered a number of internal controversies such as the failure to contain the Tabligh cluster amidst the political crisis which led to the overthrowing of the Coalition of Hope (Pakatan Harapan)-led government by a group of politicians, insufficient supply of face masks and exorbitant pricing, and poor treatment of foreigners, among others.

As for the third wave of COVID-19 in Malaysia, it is believed to have started following state elections in the East Malaysia state of Sabah in September. Just a few weeks before the election, Sabah was already reporting an increase in the number of infections as a result of a prison cluster that eventually spread to the community.

Despite calls from many quarters to delay the elections, the government stubbornly went ahead with campaigns starting on 12 September, ending with polling day on 26 September. Local media reported that politicians travelled in and out of Sabah, and from numerous posts on social media, it was evident that many of them did not wear face masks and adhere to preventive measures while campaigning.

It is alleged that politicians and their entourages were exempted from quarantine measures throughout the whole election campaign period. Politicians who travelled to East Malaysia to campaign were also exempted from quarantine when they returned to West Malaysia.

It is also important to note that there was no compulsory COVID-19 screening done for all Sabah returnees during the campaign. This then helped spread the virus from Sabah to other states in West Malaysia.

This perceived “double-standards” by the government coupled with poor management of the third wave, angered and frustrated the people of Malaysia who had obediently followed lockdown protocols themselves at the expense of their jobs and livelihoods.

"I am with the majority of Malaysians on this. Politicians have to stop their scramble for power and positions. There is nothing to be gained from this," said Malaysian epidemiologist, Malina Osman.

Even Malaysia’s King, the Yang di-Pertuan Agong Al-Sultan Abdullah Ri'ayatuddin Al-Mustafa Billah Shah, in October, urged politicians not to drag the country into another round of political uncertainty, as they had done in early 2020. In November 2020, Muhyiddin finally admitted that the Sabah state election was the cause of the latest wave of COVID-19 infections in the country.

Malaysians have also criticised the poor communication of COVID-19 SOPs following the third wave. According to local media, there were also double standards that were practiced in terms of SOPs with two sets of rules – one for officials, and another for the general public.

For example, people were getting fined for not wearing a face mask, however, politicians who were seen without face masks mingling in large groups, got away with it, unscathed.

Parts of Malaysia are currently under another round of MCO, while some states are under CMCO. Nevertheless, the situation is indeed different than the first order last year when daily cases would dip to single-digit or even zero. Confusing SOPs is perhaps a reason for this.

Immunisation Programme

Despite Malaysia’s political dysfunction, it has somehow managed to pull together a COVID-19 inoculation plan; albeit later than most.

The first phase of the programme which began yesterday will involve vaccinating a total of 500,000 medical and non-medical front-liners, and is expected to wrap up by April.

Phase two will involve those aged 60 and above, the disabled community, and others in high-risk groups such as those with heart ailments, obesity, diabetes, and hypertension. An estimated 9.4 million people are projected to receive the vaccine under the second phase which will be from April to August, 2021.

The third phase of the programme will involve the remaining group, Malaysians aged 18 and above, with vaccinations to be carried out between May 2021 and February, 2022.

The government of Malaysia believes that with more than 70 percent of the population vaccinated by then, herd immunity would be achieved.

Related Articles: