Singapore’s newly passed misinformation law has been grabbing headlines because it empowers government officials to order corrections to be placed next to social media and online posts they deem false.

The law came into effect in October 2019, resulting in outrage from human rights groups and tech giants such as Facebook and Google, which claim that the law is in violation of free speech.

A number of opposition figures and activists have already been ordered to place correction banners with the words "this post contains inaccurate information" next to their posts.

Last week, the Singapore Democratic Party’s (SDP) attempt to overrule a government order to correct three online posts about employment was rejected by the High Court, which dismissed the case as "false in the face of the statistical evidence against them," said Justice Ang Cheng Hock.

Failure to correct or remove statements can land Singaporeans in jail for up to 10 years and fines up to SGD1 million (US$720,000).

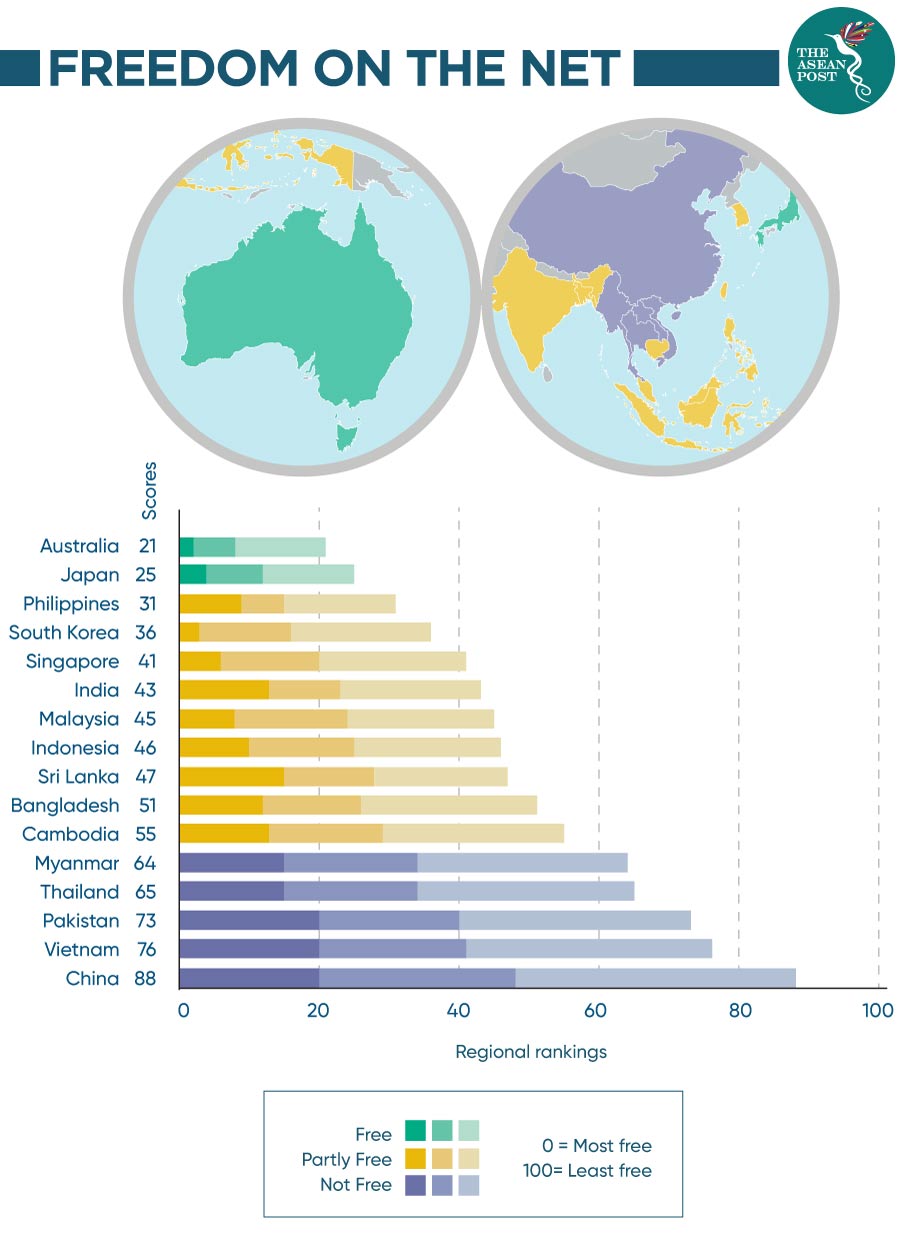

“We were very concerned about how Singapore was going to use the law when they passed it and I think our concerns have proven to be the case,” Allie Funk, research analyst at Freedom House told The ASEAN Post. “And that’s a common theme across Southeast Asia; we know the Philippines has a proposed fake news law – we have observed the term “fake news” being manipulated even in US and Europe,” she added.

2019 saw a rise in misinformation and fake news laws in ASEAN countries with the exception of Malaysia which repealed its own fake news law. Globally, these types of laws are typically prevalent in countries that have a lower ranking in the Democracy Index.

In November 2019, Thailand established an "anti-fake news" centre, with the power to monitor the online activities of its citizens – where most of those found disseminating "fake news" are those critical of the government, the military, or the royal family.

"Fake news is any viral online content that misleads people or damages the country's image," said Puttipong Punnakanta, Minister of Digital Economy and Society.

“In the Thai context, the term ‘fake news’ is being weaponised to censor dissidents and restrict our online freedom,” said Emilie Pradichit, director of the Thailand-based Manushya Foundation, which advocates for online rights.

The Philippines used to be the only ASEAN country categorised as having freedom of speech and freedom of the internet. That freedom has since deteriorated under President Duterte, who has enforced ambiguous laws that have silenced critical voices, while the media have resorted to self-censorship in order to avoid trouble with the government.

Cambodia and Vietnam have also implemented similar laws that have been observed to silence dissidents.

The growing trend of monitoring citizens’ online activities followed-up with quick prosecution by government officials is what international digital rights groups are now referring to as “digital authoritarianism.”

“Sure, there are some legitimate issues that need responding – but it needs to be responded to in a way that serves and protects human rights,” said Funk. The hefty financial penalties and jail terms are especially concerning in the context of human rights. If citizens live in fear that what they say about the government may land them in jail, the practice of self-censorship will inevitably undermine the argumentative nature of democracy.

A 2019 report by watchdog organisation, Freedom House argues that international human rights laws established by the United Nations (UN) is a sufficient benchmark to implementing misinformation laws that do not violate human rights. The broad “take out content we don’t like” approach by governments is a gross abuse of power legitimised by these laws.

Citizens should have the right to argue their case in court, with an independent content judiciary system that would not allow the decision to fall on any one government minister. Citizens have the right to appeal court orders and remedy that claim.

While this view may seem idealistic, it is one shared by the majority of citizens that value internet and press freedoms, not to mention human rights. Though it still has far to go, Malaysia is an example of how the population could reverse laws that violate their freedoms and rights.

Related articles: