The recent Mount Mayon eruption is the 52nd eruption to date since 1661.

The Philippine Institute of Volcanology and Seismology (PHIVOLCS) raised the alert level to four on a scale of five on Tuesday, indicating that a hazardous eruption could take place at any moment.

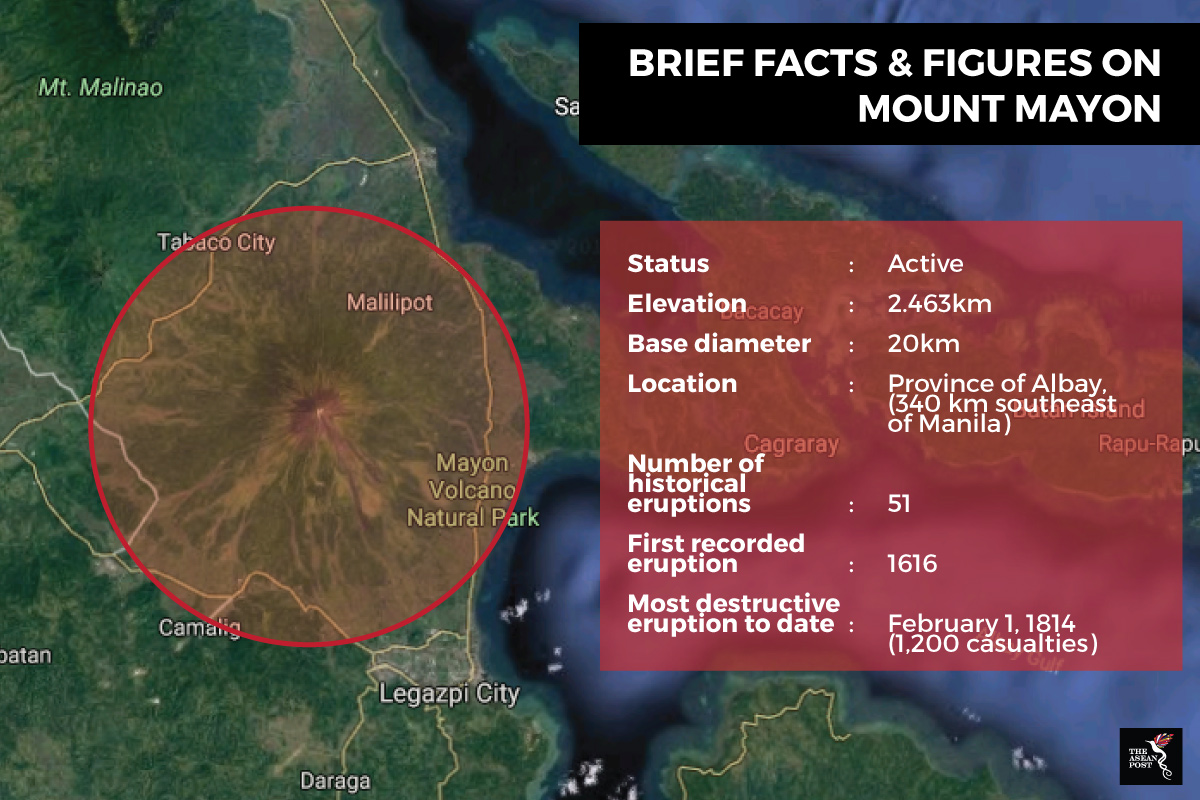

It also raised the danger zone radius from seven to eight km of the volcano’s crater. Mount Mayon entered a new eruptive phase on 13 January, according to PHIVOLCS, which uses a range of techniques such as visual observations, seismicity and gas emissions to monitor volcano activity.

Mount Mayon is characterised as a stratovolcano, meaning a volcano consisting of multiple layers of lava and ash. In the past, its eruptions have occurred within 10 years of one another, usually beginning with effusive eruptions.

These then progress into weak to moderately explosive eruptions consisting of lava flows, tephra (volcanic ash) and pyroclastic flows.

The United States Geological survey defines pyroclastic flows as hot lava blocks, pumice, ash, and volcanic ash that moves at high speed down a volcano. These can reach temperatures of up to 1,000 km and travel at speeds of up to 80km per hour.

PHIVOLCS director Renato Solidum predicted the possibility of either continuous lava eruptions to take place or pyroclastic flows.

What happens next would depend on the results of further geodetic and geochemistry tests being done to study earthquake strength, gas content, and other seismic movements, explained PHIVOLCS volcanologist Ed Laguetta.

"In 2014, Mayon ran out of gas which prevented an eruption from happening. We need to measure gas now. We need to be sure how strong the eruption would be," he added.

As of today, there have been no reports of injuries or casualties from the Mount Mayon eruption. Yet the Philippine government has had to relocate around 56,000 locals to evacuation 46 camps.

Extremely acidic gases like sulphur dioxide and hydrogen dioxide could be dangerous to breathe in when mixed with water vapour, to form volcanic fog. The more poisonous fluorine gas, on the other hand, has a corrosive quality and can be absorbed by vegetation – exposing humans and animals to the dangers of poisoning long after the volcanic eruptions have ended.

Despite the potential dangers, local farmers still opt to live and cultivate land surrounding Mount Mayon. This land has proven to be rich in minerals like phosphorus and potassium allowing farmers to grow coconut, vegetables, abaca and palay, among other crops there.

Soil formations nevertheless take years to develop, said Dian Fiantis, professor of soil science at the University of Andalas along with Budiman Minasny, Sydney University professor of soil-landscape modelling and Anthony Reid, emeritus professor with the Australian National University.

It is through much biological and chemical weathering that the ashes will release their nutrients. According to the three experts, solutions would need to be undertaken to quicken the rate of soil formation in order for farmers to really reap benefits.

Using Mount Agung as an example, they pointed out how Dutch scientist ECJ Mohr had observed in 1938 that areas near volcanoes were able to sustain high population densities due to the fertility of volcanic ash from the activity of the nearby volcanoes.

As long as there is a strong system for volcanic activity detection in place and quick evacuation of locals, populations should be able to thrive in these seemingly dangerous locations. In this way, governments would be able to ensure that the benefits of volcanic activity still outweigh the risks.

Recommended stories: