Xenophobic sentiments on social media against “the most discriminated people in the world” – the Rohingya of Myanmar – is on the rise in Malaysia.

A few weeks ago, it was reported that Malaysia denied entry to a boat carrying around 200 Rohingya refugees which was spotted by an air force jet off the north-western island of Langkawi. Malaysian sailors provided the Rohingya food before escorting them out of the country’s waters.

“With their poor settlements and living conditions … it is strongly feared that undocumented migrants who try to enter Malaysia either by land or sea will bring (COVID-19) into the country,” read a statement by Malaysia’s air force.

To date, more than three million people have been infected with the deadly coronavirus. The pandemic has prompted governments to imposed drastic measures to contain the outbreak. In Malaysia, 100 people have succumbed to COVID-19, as of 28 April. The country has enacted its nationwide partial lockdown, also known locally as the Movement Control Order (MCO) since mid-March and is due to end on 12 May. This has led to the closure of border gates and the barring of foreigners from entering the country.

"Receiving the Rohingya at times like this could open the floodgates for more foreign nationals and vessels to approach the Malaysian border and therefore hinder the government's effort to fight Covid-19,” said Mohamad Hasan, deputy president of the United Malays National Organisation (UMNO). He also said that the country has “far exceeded” its capacity to host refugees.

The Human Rights Watch (HRW) has criticised Malaysia for turning its back on the Rohingya asylum seekers, especially during the time of a health crisis.

“… the pandemic does not justify a blanket policy of turning away boats in distress, risking the right to life of those onboard. Malaysia’s pushback policy also violates international obligations to provide access to asylum and not to return anyone to a place where they would face a risk of torture or other ill-treatment,” noted the HRW in a recent statement.

The conflict intensified when a self-proclaimed leader of the Rohingya – Zafar Ahmed Abdul Ghani –alleged to have demanded citizenship and equal rights for the Rohingya community in Malaysia. This sparked further outrage among Malaysians. A few anti-Rohingya petitions were then posted online, demanding that the refugees be deported from Malaysia. It was reported that one petition gathered over 20,000 signatures before it was taken down as it was considered as hate speech.

In response to the statement made by Zafar Ahmed Abdul Ghani, non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and advocacy groups representing Rohingya refugees have apologised to the Malaysian government and urged authorities to take stern action against the president of the Myanmar Ethnic Rohingya Human Rights Organisation in Malaysia (Merhom).

"We, the Rohingya refugees, have never elected Zafar Ahmed as our president. He is not our leader, in fact, we have no leader in Malaysia, and he has no right to issue statements on our behalf,” they said in a joint statement signed by 17 Rohingya groups.

“He has been used by our enemies both here and in Myanmar to tarnish our image and disrupt our temporary peaceful refuge in Malaysia, while waiting to return to Myanmar or resettle in third countries," the statement noted.

Rohingya In Malaysia

A deadly crackdown by Myanmar’s military in 2017 on Rohingya Muslims have sent many of them fleeing the country. The United Nations (UN) described the violent episode as a “textbook example of ethnic cleansing”. Nevertheless, the government of Myanmar has denied all allegations of genocide. Despite having lived in Myanmar for generations, the government doesn’t recognise them as citizens.

Following the war crimes against the Rohingya in Myanmar, hundreds of thousands of them have fled the country to escape abuse and discrimination. Some of the countries they have journeyed to include Bangladesh and Malaysia.

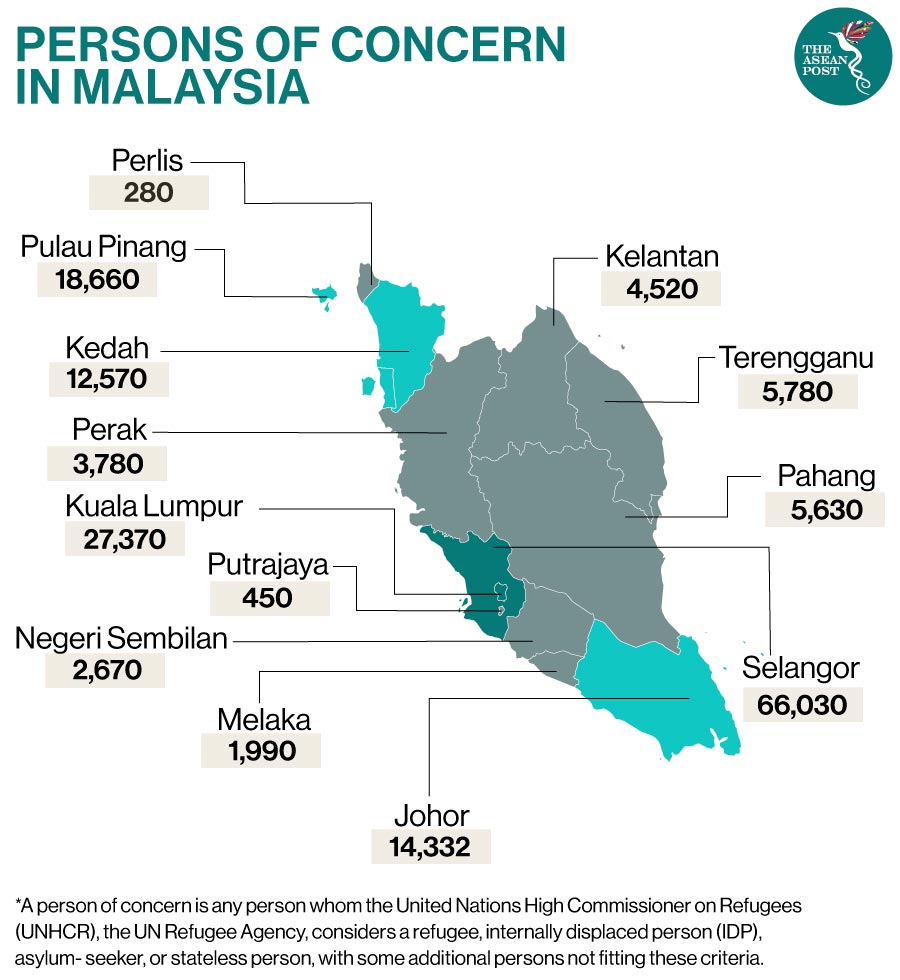

According to the United Nations Refugee Agency (UNHCR), as of February 2020, there are some 178,990 refugees and asylum seekers registered with the agency in Malaysia – the majority are from Myanmar, comprising some 101,010 Rohingya.

As racist remarks against the Rohingya refugees rise on Malaysian social media, the community has expressed fears that they will be deported to an unknown destination as Myanmar is currently unsafe for them to return to.

"I have no idea whether I will be able to go back. I just hope I can go back to my hometown with full rights and dignity one day," a Rohingya activist told local media.

"We, the Rohingya refugees in Malaysia, are worried and in a state of fear due to the growing negative sentiments against us as a result of such statements,” said Rohingya groups.

Malaysian activist and lawyer, Nurainie Haziqah explained to the media that “entitlement” of Malaysians “who think only Malaysians deserve help” is perhaps one of the most common reasons for the hate against the community.

“There are widely held sentiments that the Rohingya take advantage of the kindness and generosity shown by Malaysians, that they are dishonest and engage in criminality, that they take away job opportunities and business from locals,” said Thomas Benjamin Daniel, a senior analyst with Malaysia’s Institute of Strategic and International Studies (ISIS).

Nevertheless, many Malaysians are unaware that the country is not a signatory to the 1957 Refugee Convention, or its subsequent 1967 Protocol which highlights that refugees should be given the right to earn a living, access to education and freedom of movement. Unfortunately, this means that refugees in Malaysia are considered undocumented migrants – preventing them from securing a job legally and other rights such as formal education.

Thomas Benjamin Daniel suggests that the Malaysian government should step in and reassure locals that “their needs are not being diluted in favour of refugees”.

Tengku Emma Zuriana, the ambassador to Malaysia from the European Rohingya Council published an open letter pleading for ASEAN member states to “extend their compassion to those in immediate danger at sea.”

In early April, a special online summit was held among Southeast Asia’s leaders to discuss strategies that could be taken at a regional level to combat the deadly COVID-19 pandemic. However, it failed to discuss the plight and wellbeing of refugees and migrants. To date – ASEAN has not been able to effectively address the violence that pushes the Rohingya community out of Myanmar, stated Tengku Emma Zuriana in her letter.

“ASEAN states must ensure that policies on COVID-19 uphold everyone’s rights and do not jeopardise people in need of humanitarian assistance and international protection.”

Malaysian politicians have also expressed their concerns regarding the racist attacks on the Rohingya online. Senior Minister Ismail Sabri Yaakob urged Malaysians to remain calm and not raise issues that can incite anger, adding that “Malaysia is a peaceful country and we are considerate to anyone on our soil.”

Anwar Ibrahim, a prominent political figure in the country has also addressed the issue in a Facebook video. “I think we should safeguard our humanity. As we guard our borders, we cannot let people die, moreover they are the victim of tyranny by their own government,” he said.

Related articles: