After decades of impressive growth, for the first time, Southeast Asia is experiencing a drop in measured human development. The economic fallout from the COVID-19 pandemic will likely take months to reveal itself and years to put right. Yet, a legacy of mobilising under constraints is leading Southeast Asia’s pandemic response.

During the first two months of COVID-19 lockdown, the once bustling streets of Bangkok were unusually quiet. In the alley nested between two high-end shopping malls in downtown Bangkok, an elderly couple were not at their usual rice cart. Their regulars, motorbike taxi drivers and shop assistants, were absent. The couple have not returned now that things have eased. A Thai blind massage team shared, in our recent dialogue, that for them, no tourism equals no clients and no income.

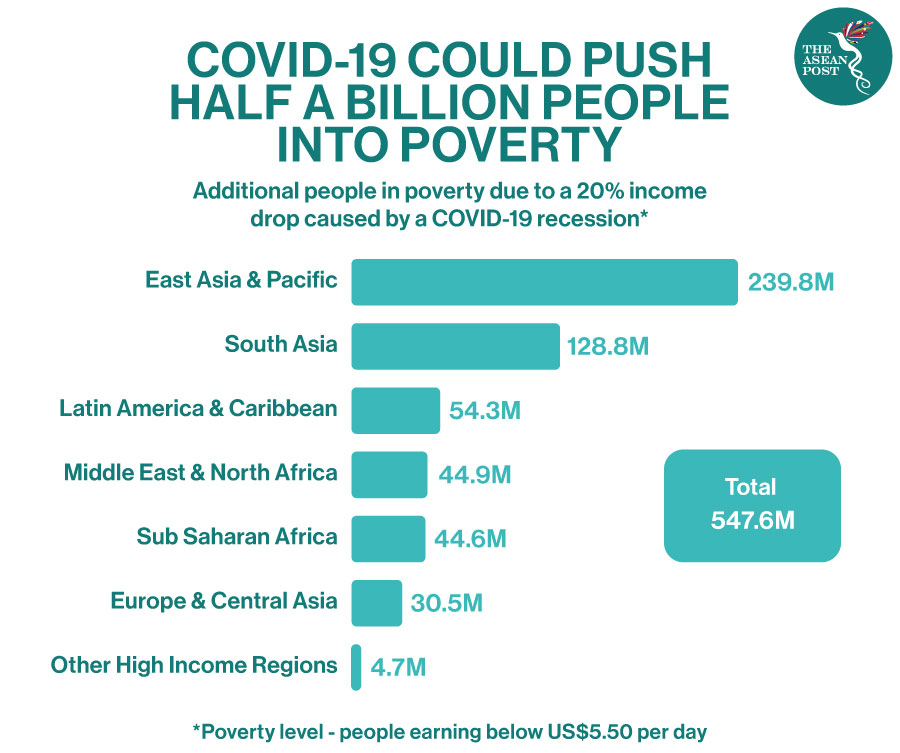

Similar tales of woe can be heard in many other poor communities across Southeast Asia. Garbage pickers in the slums outside Manila; temporary workers living outside industrial zones in Ho Chi Minh city; undocumented migrants and refugees living along the borders of Malaysia, Myanmar and Thailand. They are among the 177 million people (below the US$5.5 poverty line) that the World Bank now estimates will slip into poverty.

No Strangers To Calamities

Southeast Asian communities are no strangers to calamities. In those times, they could probably turn to a relative, a friend or a neighbour for help. Or work extra to make up for the lost income. But the usual informal safety net only works if some are spared from the disaster. The COVID-19 pandemic does the exact opposite, striking everyone down at the same time.

Closed restaurants need no kitchen hands; street hawkers and motorbike taxis are idle when all stay at home; empty hotels need no cleaning. The new brief by the United Nations (UN) Secretary General shows that Southeast Asia’s gross domestic product (GDP) is estimated to contract on average by 0.1 percent in 2020 with 218 million informal workers having their livelihoods at risk.

The informality of work means that they are not protected by any formal social safety nets. Even before the crisis, our analysis shows that 60 percent of the population in Asia and the Pacific had no protection when they become sick, disabled or unemployed. Many are so invisible that they would not even figure in the statistics.

The prolonged drought in much of Southeast Asia and the looming monsoons in the coming months may risk sweeping away the few assets they have left. Their hopes for the future, investment in their children’s education, look grim. Poor children without internet access, computers and smart phones cannot readily jump into remote learning during school closures. Without safety nets, either formal or informal, to fall back on, many will inevitably slide into poverty with no clear respite in sight.

Yet good news has come from Southeast Asia. The region was among the first to be hit by the pandemic and contains some of the countries with the greatest success in curbing it, including Vietnam and Thailand. Governments have been quick to roll out fiscal packages to help affected businesses and households.

Local Initiatives

Our review of COVID-19 responses reveals a diverse mix of relief packages including support for health responders, subsidies for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), wage subsidies and direct cash transfers for vulnerable populations.

The myriad of local initiatives is another source of great hope. In Thailand, local voluntary groups have quickly come together to locate and provide essential packages to the most in-need communities, including those unregistered. New ways of providing health support have emerged such as teleconsultation for rehabilitation in Singapore and targeted telehealth services for children with disabilities in Malaysia.

These good practices were shared in our recent dialogue for protecting and empowering persons with disabilities. Permeating these practices is a strong sense of coming together from both the public and private sector.

The crisis has also shown that limited fiscal space and resources have not stopped countries from supporting their people. Measures that once were thought to be expensive such as establishing universal health care and broadening social protection coverage are now rightly seen as essential investments in people.

Measures that were seen as luxuries such as securing internet for all are now recognised as a lifeline especially for poor and vulnerable communities including refugees and migrants. Measures that would help us respond faster to crises such as providing people with basic legal identity are now a must.

Southeast Asia’s long road to recovery has started. Time will tell if the emergency measures can be “locked in” to help address the region’s deep inequalities and put it on a green recovery path as advocated by the UN Secretary General in his recent brief on COVID-19 in Southeast Asia. Only then will the people of Southeast Asia be more resilient in any future crisis.

Related Articles: