Singapore has a problem and it's two-fold. On the one hand, it is an ageing country. Singapore falls under the ageing high income market bracket which has limited demographic wiggle room to maximise growth potential. Singapore is projected to reach a high old age dependency ratio of over 25 percent by 2025. The old age dependency ratio is a measure of the number of elderly people as a share of those of working age.

Concerns are further escalated following a study by Cisco and Oxford Economics which revealed that out of all ASEAN-6 countries (Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam), Singapore will likely see the highest job displacement thanks to Industry 4.0.

On the other hand, Singapore isn’t producing enough babies to make up for its ageing population.

In March, Minister in the Prime Minister's Office Josephine Teo revealed that Singapore’s total fertility rate (TFR) dropped to 1.16 in 2017, making it the lowest figure since 1.15 in 2010 and the second lowest ever recorded for the country.

Statistics on the TFR - which measures the average number of children per woman - have been available since 1960. The 1.16 mark continues a declining trend since 2014 (1.25), 2015 (1.24) and 2016 (1.20).

Need for foreign manpower

Being an ageing country and having a low fertility rate, it’s no wonder that Singapore is forced to bring in so many foreign workers.

In 2014, the Ministry of Manpower announced the Fair Consideration Framework (FCF) which requires employers to consider Singaporeans fairly for all job opportunities before hiring Employment Pass (EP) holders.

One of the key requirements of the FCF is that firms making new EP applications must advertise the job vacancy on a new jobs bank administered by the Singapore Workforce Development Agency (WDA). Each advertisement must be open to Singaporeans and run for at least 14 calendar days.

In July, the Ministry of Manpower broadened the FCF advertising requirement to firms with 10 or more employees and job positions that pay a fixed monthly salary of less than SGD15,000 (US$10,984). Previously, firms with 10 to 25 employees and jobs that pay from SSD12,000 (US$8,787) to below SGD15,000 (US$10,984) a month were exempted.

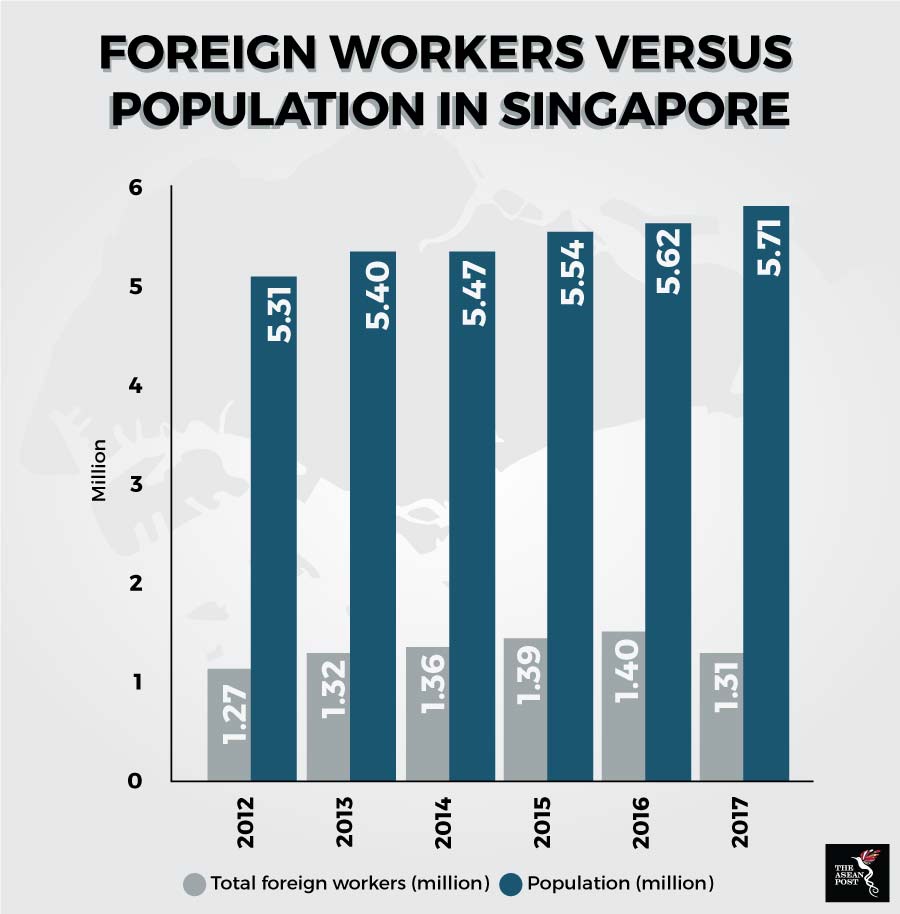

The FCF was born out of the need for Singapore to address its high number of foreign workers. According to Ministry of Manpower statistics, foreign worker numbers reached an all-time high in 2016 with approximately 1.4 million foreign workers compared to the 5.62 million population.

However, unless the low fertility rates are addressed effectively, there does not seem to be an end to the influx of foreign labour. In fact, Singapore’s Education Minister Ong Ye Kung recently said that the government intends to bring in foreign talent in areas critical to Industry 4.0. Ong said that meanwhile, the country will work on rebalancing its education system to meet future demand. The idea is that foreign talent will be able to help the country achieve its target of becoming a “Smart Nation” while schools prepare current students to fill in those roles later.

Source: Various sources

A ray of hope?

A local news report found that while fertility rates remain at an all-time low, baby-related businesses are actually enjoying a boom. This has been attributed partly to increased individual wealth, as well as larger social networks, government endeavours, the gig economy, and e-commerce.

Citing online research website Statista, the report noted that the sector for toy manufacturing has earned US$154 million this year and most likely will be growing by over 20 percent per year, with a projected market worth US$320 million by 2022.

“The government is also doing its part in encouraging people to have more babies, including offering benefits and cash grants - and in the process has also helped to grow the childcare industry,” the report noted, pointing to the Singapore Health Promotion Board’s implementation of the World Health Organisation’s (WHO) Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative (BFHI) guidelines.

The guidelines specifically pertain to breastfeeding in public hospitals and have caused a surge in the demand for products and services related to breastfeeding, with lactation biscuits as one example.

Whether or not this boom in baby-related businesses will translate to a higher fertility rate is yet to be seen. However, it at least signals that Singaporeans aren’t afraid to spend on their children and are affluent enough to do so. The government, however, must still address issues like expensive childcare, and possibly work flexibility options for mothers or future mothers.

Related articles: