The Philippine’s Eastern Visayas islands of Samar and Leyte bore the brunt of Typhoon Haiyan as it made landfall in November 2013, leaving in its wake a trail of destruction affecting 14 million people. The record-breaking typhoon that created a storm surge of up to 19 feet caused more than six thousand deaths, damaged over one million homes, and displaced over four million people.

The economy and people’s livelihoods were also not spared. It was estimated that 5.6 million workers were affected by the typhoon, 2.5 million of whom were poor people. Agriculture and fisheries, the main sources of livelihood for the area, were mostly decimated.

Following the disaster event, then Philippine President Benigno Aquino Jr. announced the introduction of the controversial strategy of “no-build zones” (NBZs), aimed at reducing long-term disaster risk and displacement due to natural disasters. Under the proposed NBZ policy, an area is categorised as low-, medium- and high-risk, with appropriately recommended disaster mitigation measures for a particular level of risk, including the relocation of whole communities.

Flawed implementation

A swath of 40-metre wide coastal land was designated as an NBZ, even as local hazard maps indicated that storm surges could go well beyond that distance. Experience from Haiyan showed storm surge travelling up to more than one kilometre inland in certain areas. The NBZ recommendation also did not apply to rebuilding for livelihood and commercial purposes, such as hotels and restaurants.

Issues also arose for those who were relocated, with some already rebuilding within the NBZ’s boundaries on their own. Returning victims of Haiyan cited lack of livelihood options and a lack of urgency in determining their new homes. Some were relocated to housing projects without access to public services such as water, power and social services.

According to climate relocation expert, Alice Thomas, in her publication, ‘Resettlement in the Wake of Typhoon Haiyan in the Philippines: A Strategy to Mitigate Risk or a Risky Strategy?’, determining safe areas requires conducting mapping for multiple hazards, including but not limited to floods, typhoons, landslides, earthquakes and more. This requires financial and technical capacities, which were inaccessible to the small and underfunded local government units.

“Complicating matters, in some municipalities like Guiuan in Eastern Samar (which is surrounded by the ocean on almost all sides and where the typhoon first made landfall) multi-hazard mapping, eventually undertaken with the assistance of international agencies, revealed that there were very few areas that were actually safe,” she wrote.

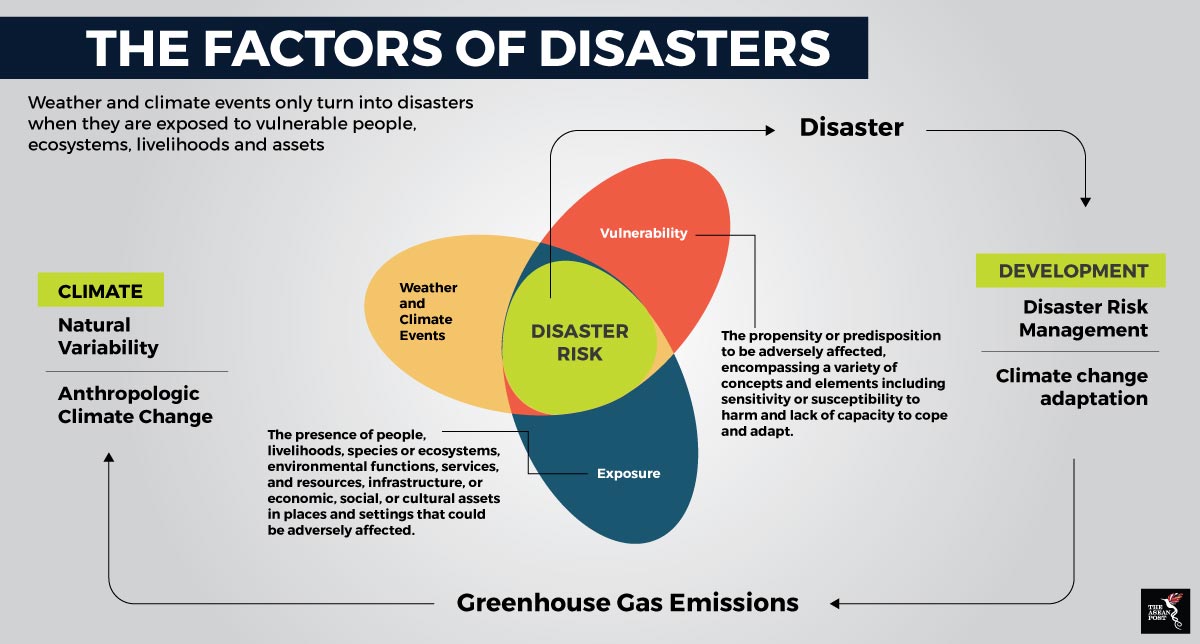

Source: Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

Local communities as agents of adaptation

In Guiuan at the southern end of Samar island, the community is opting instead to build on their capacities, lowering their vulnerabilities, and reducing their exposure through community-based initiatives. According to David Garcia, a geographer and urban planner working on post-Haiyan rebuilding work under the United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-Habitat), the community-based initiatives treated people as agents of resilience in their own places.

“In Guiuan, resilience is not only built by design but also nurtured by relationships. Theirs is a model based on a better understanding of people in places as agents of adaptation. The townsfolk were able to organise themselves into institutions capable of addressing vulnerability and building capacity,” said David.

Among the initiatives undertaken by the community include establishing community-based organisations for fisherfolks and seaweed growers that act as guardians to the largest marine protected area and barrier reef in Eastern Visayas, as well as operators of fish cages and seaweed frames that can be lowered before a storm. The community is also involved with constructing stronger houses in a household-led recovery and rebuilding initiative that gives families a voice in determining the design, budget and selection of the contractor.

A collaboration between the women’s association, the local government and non-government organisations resulted in building of evacuation centres in low-risk areas. A year after Haiyan, when Typhoon Hagupit made landfall on their island, no casualties were recorded - despite torrential rain, storm surges and severe winds for 12 hours - due to successful evacuation.

Understanding the needs and capabilities of a community enables not only a response that is systemic, effective and sustained over time. It also designates local communities as agents of change, instead of limiting them to just being disaster victims. It is a lesson to be learnt for other at-risk communities and governments in the region.

Related articles:

Warning of 1.5 degrees Celsius warming