In April 2017, the European Parliament passed a resolution restricting the import of uncertified palm oil. The resolution resulted in strong condemnation from Malaysia and Indonesia, which together produce 85 percent of the world’s palm oil.

Just two months later, 13 European Union (EU) member states signed the European Soya Declaration at the Agriculture and Fisheries Council in Brussels, with the purpose of supporting soybean cultivation in Europe.

However, it seems the biggest winner of this declaration is in fact the United State (US), which saw a 121 percent increase in soybean exports to Europe in 2019 according to the European Commission (EC). Brazil was formerly Europe’s leading source of soybean but the South American nation’s exports to the EU decreased from 34 percent in 2017/18 to 21 percent in 2018/19. Imports for US soybean to the EU jumped from 36 percent to 72 percent during the same period.

The US-China trade war has left the US sitting on a 49 million tonnes soybean stockpile after both parties slapped additional tariffs on shipments. Further tariffs on Chinese goods in August 2019 caused a sharp fall in soybean exports that the US did not expect to be reversed.

US soybean traders have been working to sell the surplus, “unfortunately it doesn’t look like we’ll quite get there this year,” Jim Sutter, Chief Executive Officer of the US Soybean Export Council, told local media. He added that they will be “intensifying” marketing strategies globally to regain demand by developing new markets, especially in Europe where US soybean export have traditionally fared well.

According the US Department of Agriculture, China accounted for 60 percent of US soybean exports before the trade war. Despite the similarity of soybean prices in Brazil and US (including a 25 percent tariff), China tripled its order for Brazilian soybean.

“The government’s signal on this is clear - do not buy US beans,” a senior analyst with a major futures brokerage in China said. “Basically, all shipments for the fourth quarter are from Brazil even though prices of Brazilian beans are very high.”

It is estimated that China imported 14 million tonnes of Brazilian soybeans in the last quarter of 2018. Due to Brazil’s poor soil quality, the easiest method by farmers there to meet Chinese demand is to clear Amazon forest land.

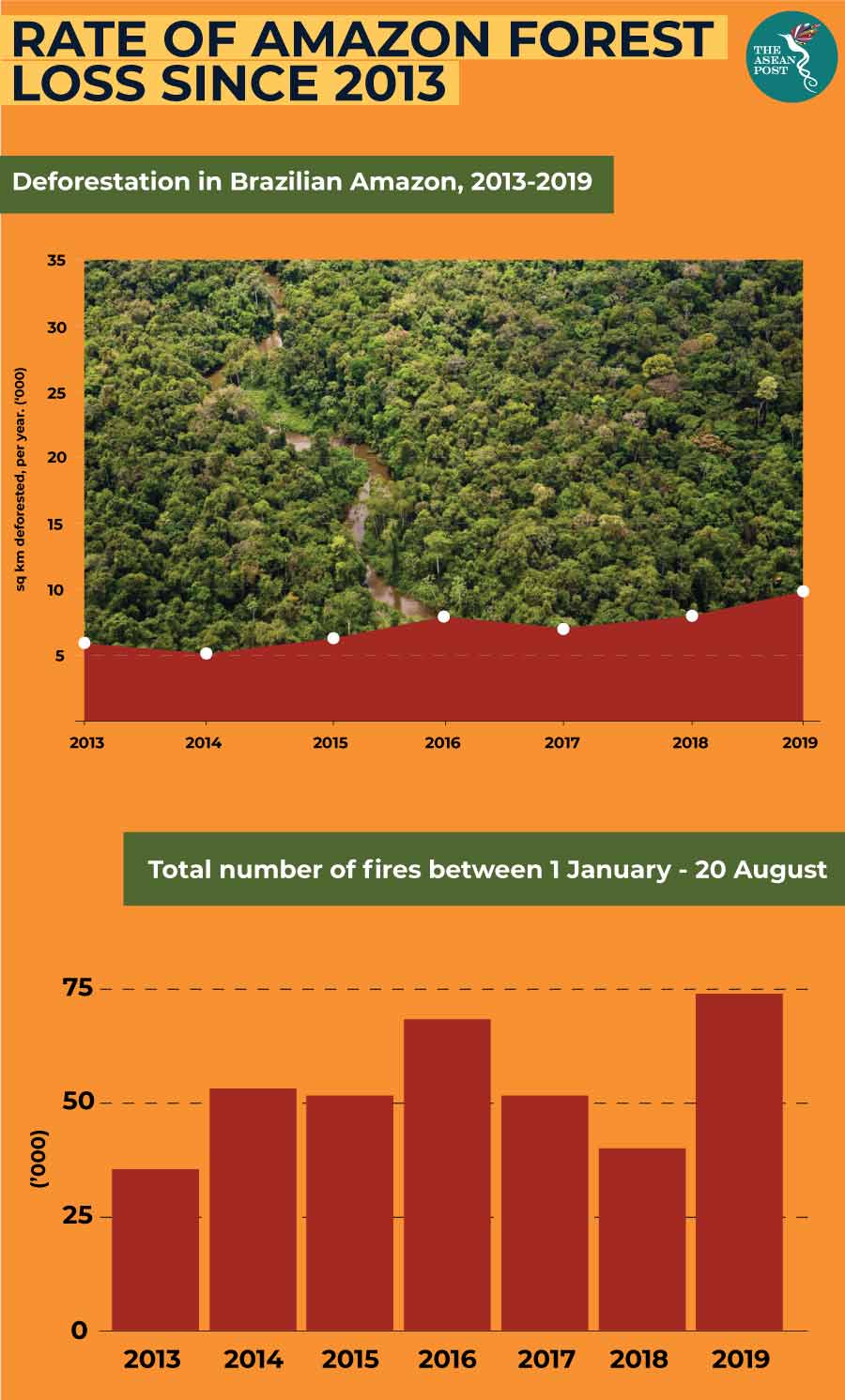

In August 2019, major public outcry erupted when news that the Amazon rainforest was on fire broke.

According to the Amazon Environmental Research Institute (IPAM), the recent increase in the number of fires in the Amazon forest is directly related to intentional deforestation and not the result of an extremely dry season.

IPAM's director, Ane Alencar said that fires were often used as a way of clearing land. "They cut the trees, leave the wood to dry and later put fire to it, so that the ashes can fertilise the soil.”

This is an obvious subsequence to the phasing out of palm oil in biofuels and the EC’s decision to authorise the replacement of soybean oil for biofuel in January 2019, which had previously failed to be certified as sustainable.

One of the main driving factors behind the EU’s decision to restrict palm oil is the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) set by the United Nations (UN), intended to be achieved by 2030. This is indicated in both, the 2017 resolution and the Soya Declaration.

The EU benefitted from the trade war between China and the US by sourcing the US’s rejected soybean oil at a much cheaper rate than the Brazilian alternative. While also separating itself from the environmental damage associated with the oil palm industry, of which it played a significant role in expanding since the 1980’s.

The palm oil controversy occurred simultaneously with the US-China trade war, affecting each other and resulted in an indisputable increase in carbon emission and biodiversity loss.

The banal fact here is that China has much lesser concerns for the environment and its practices with Brazil is unethical. However, a closer analysis illustrates the EU’s failure to utilise its leverage on both, the palm oil industry as well as the trade war in a global effort to drive sustainability.

For example, it abandoned the palm oil market even though the threat of a ban already forced Malaysia’s Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad to pledge a permanent halt to deforestation. This would have meant that the EU could have dispensed stronger monitoring efforts to ensure long-term compliance for environmental and human rights protection in the plantations.

Additionally, despite early warnings by Nature, a leading multidisciplinary science journal, that the Amazon forest may become a victim of the trade war, the EU failed to pressure the US and China to reach a compromise to prevent biodiversity loss to the South American rainforest.

Contradictory environmental policies could jeopardise the cooperation the EU needs to effectively tackle pressing threats on biodiversity. The single-minded rush to achieve SDG goals by 2030 will not mean much if it ultimately leads to an increase in global carbon emissions.

Related articles: