The ASEAN Post recently published an article on the Swiss-based International Institute for Management Development (IMD) World Talent Ranking for 2019. In the article, the focus was on the wide gap between Singapore’s performance with that of other ASEAN countries included in the study.

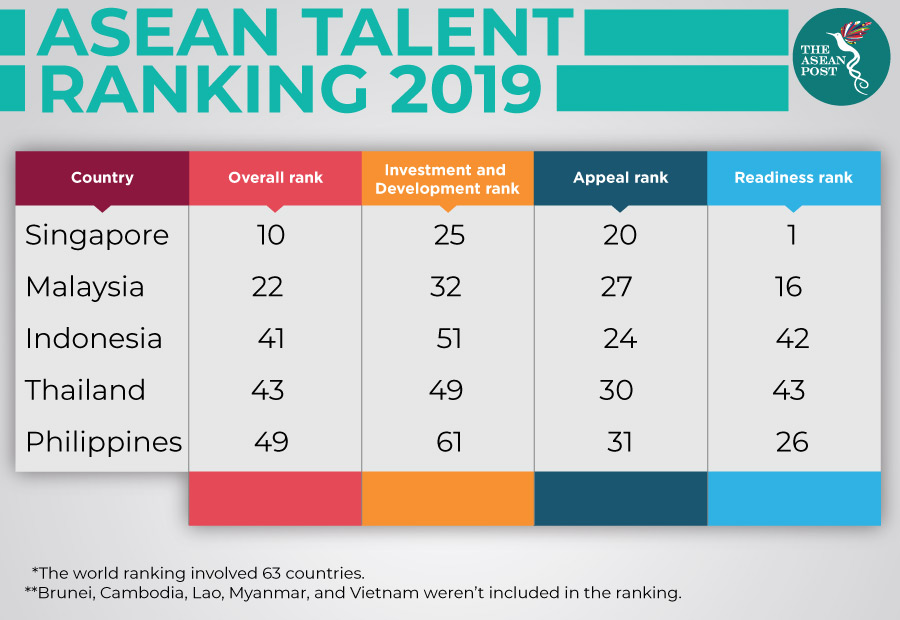

The ranking involved 63 countries from around the world, including five ASEAN member countries (Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore and Thailand).

Of the five ASEAN states, the IMD World Talent Ranking placed the Philippines lowest. Singapore came in 10th spot, Malaysia was placed 22nd, Indonesia at 41st, Thailand at 43rd, and then the Philippines in 49th spot.

At first glance, this ranking may paint a damning picture for the Philippines. But look a little closer and the picture isn’t as bad as it immediately seems.

Yes, the Philippines did only capture 49th spot out of a survey of 63 countries. Yes, the country was ranked 61st out of 63 spots for Investment and Development. Nevertheless, what should not be taken for granted is the fact that, out of the five ASEAN countries, the Philippines saw the most growth.

According to the IMD report, the Philippines managed to jump six spots compared to last year’s talent ranking. Singapore jumped three spots, Malaysia maintained the same position as last year, Indonesia jumped four spots, and Thailand actually went down a spot.

The Philippines’ jump of six spots this year certainly paints a much more positive picture than the IMD World Talent Ranking of 2018 did. The Philippines had – in fact – dropped a total of 10 places to 55th spot. In 2017, the Philippines was placed 45th.

But more than this, is the fact that the Philippines didn’t do too badly as far as the Readiness factor went where it ranked 26th. This was, in fact, better than Indonesia which ranked 42nd, and Thailand which ranked 43rd. The Philippines also ranked 31st for Appeal.

According to the IMD report, rankings were obtained by looking at three main factors: Investment and Development, Appeal, and Readiness. For Investment and Development, what the IMD looked at was the investment in and development of home-grown talent. For Appeal, the IMD looked at the extent to which a country taps into the overseas talent pool. Thirdly, for Readiness, the IMD looked at the availability of skills and competencies in the talent pool.

“Finally, to compute the overall World Talent Ranking, we aggregate the criteria to calculate the scores of each factor which function as the basis to generate the overall ranking,” the IMD explained in its report.

Investment and development

Judging from the numbers, it’s obvious that the Philippines’ overall ranking in 2019 was affected by its investment in and development of home-grown talent. This, however, is not to say that the Southeast Asian country is not trying.

Education spending was increased, and between 2005 and 2014, government spending on basic education more than doubled. According to data from the World Bank, spending per student in the basic education system reached P12,800 (US$246) in 2013, far above what was recorded in 2005.

Later, in 2017, allocations for the Department of Education were increased by 25 percent, making education the largest item on the national budget. In 2018, allocations for education reached P533.31 billion (US$10.26 billion), or 24 percent of all government expenditures – the second largest item on the national budget. The higher education budget, likewise, was increased by almost 45 percent between 2016 and 2017. Meanwhile, 86,478 classrooms were constructed, and over 128,000 new teachers hired between 2010 and 2015.

Nevertheless, according to the World Education News & Reviews (WENR), run by the not-profit organization World Education Services, there are still a variety of education indicators where the Philippines trails behind its ASEAN neighbours.

“Strong disparities continue to exist between regions and socioeconomic classes – while 81 percent of eligible children from the wealthiest 20 percent of households attended high school in 2013, only 53 percent of children from the poorest 20 percent of households did the same. Progress on some indicators is sluggish, if not regressing: completion rates at the secondary level, for example, declined from 75 percent in 2010 to 74 percent in 2015, after improving in the years between,” the WENR reported.

“Importantly, the Philippine government continues to spend less per student as a share of per-capita GDP than several other Southeast Asian countries, the latest budget increases notwithstanding.”

It’s clear that the Philippine government must do more in terms of investment and development in its talent. While the government has been more focused on this area, there is still a lot of room for growth. Nevertheless, it is hoped that educational reforms put in place will eventually bear fruit.

Related articles: