Currently, in a dining room of a house in a city, a nine-year-old child sits in front of his laptop engaging in a class through Zoom or Google Meet. Next to him is his little sister, slightly younger, on her new tablet with earphones on, attentively listening to her English teacher. All her 15 classmates are connected as well.

At the same time, a 10-year-old boy, miles away, is taking turns with his five other siblings to use the only tablet they own to connect to his online classroom via Zoom. His teacher sometimes sends him homework through WhatsApp, but he can only access it at night through his father’s smartphone when he returns home from work. He has not seen most of his classmates for many months and has not even heard from some of them as they are rarely online. Connection issues, perhaps.

These dramatically different experiences are happening right now across the world in countries like Indonesia, Kenya, Colombia, and the Philippines, among others.

“This pandemic has generated suffering of an unthinkable scale across the globe,” stated the World Bank. And it has been “tremendously unequal” when invading many aspects of human life, including education opportunities.

The organisation predicts large increases in dropout rates both, in secondary and higher education; and most likely the total number of schooling years of this generation to be lower.

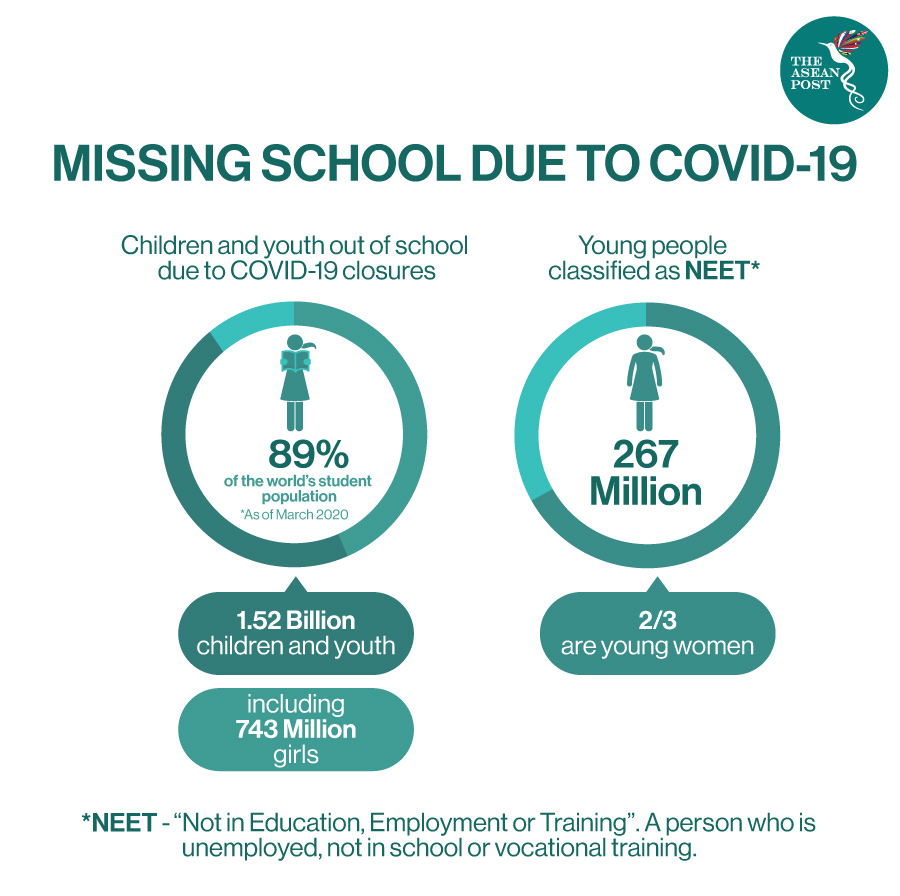

According to the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), as of 17 March 2021, some 171 million pupils enrolled at pre-primary, primary, lower-secondary, and upper-secondary levels of education and tertiary education have been affected due to school and institution closures.

This time last year, over one billion learners from all over the world had their education severely disrupted. Koumba Boly Barry, UN Special Rapporteur on the right to education called it an “education crisis.”

Education In The Philippines

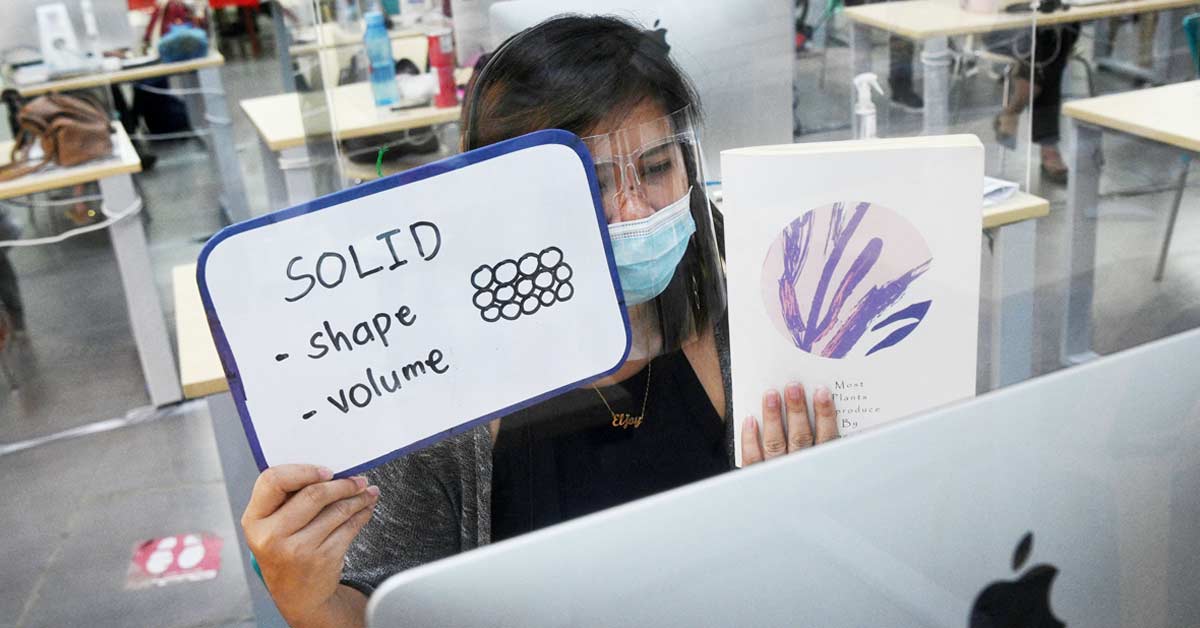

Back in June 2020, Philippine officials announced that tens of millions of children in the archipelago will not be allowed back to school until a coronavirus vaccine was available. Leonor Briones, Education Secretary said that teachers will have to use distance learning methods via the internet or TV broadcasts where needed.

A year after the COVID-19 pandemic sent the Philippines into a months-long lockdown, classrooms across the ASEAN member state remain empty and children are still stuck at home.

Fearing youngsters could contract the virus and infect the elderly, President Rodrigo Duterte refuses to lift lockdown restrictions until vaccinations are widespread.

A “blended learning” programme involving online classes, printed materials, and lessons broadcast on television and social media was launched in October. But with the shift from face-to-face learning to online learning, Philippine education now heavily relies on connectivity. Access to the internet is vital for both parties – students and teachers.

Unfortunately, millions of Filipinos live in deep poverty and do not have access to computers at home, which is also key to the viability of online classes.

“I can't do it, it's difficult for me,” said Andrix Serrano, a fourth-grader who lives inside a Manila slum shack with his street-sweeper grandmother. “It's fun in school. It's easier to learn there.”

An Economic Policy Research Institute (EPRI) report published last December titled, “The Impact of COVID-19 Crisis on Households in the National Capital Region of the Philippines” revealed that parents’ and guardians’ biggest concern in regards to education is the switch to remote learning.

Surveyed respondents expressed varied concerns regarding online learning including money for phone load, lack of gadget, bad internet, difficulty understanding lessons taught online, parents’ lack of time to spend with children on schoolwork, inability for children to focus during online classes, and parents’ lack of familiarity with lessons.

Other than that, UNICEF also noted that since the school shutdown, enrolments have dropped by more than a million in the Philippines.

"COVID-19 is affecting all school systems in the world, but here it is even worse," said Isy Faingold, UNICEF's Education Chief in the country.

Experts also worry that many students are falling even further behind and those that have dropped out might not come back to resume their education.

Moreover, classroom closures also leave children at greater risk of sexual violence, teenage pregnancy, and recruitment by armed groups, explained Faingold.

The Philippine Business for Education (PBEd) has urged the government to “take the lead in building an education system that Filipino learners deserve – one that realises their full potential.”

Earlier this year, the non-profit organisation also called on the government and other stakeholders to “stem the learning crisis now,” as it says that “protracted school closures and uncertainty in the safe and equitable reopening of our schools will further worsen the learning losses, especially for the 2.7 million unenrolled K-12 (Kindergarten to Grade 12) students this school year.”

“We have yet to see a clear plan to bring our students back to school safely,” the PBEd added.

In a recent publication on its website, the PBEd also warned that Filipino students are losing thousands of pesos in projected annual future earnings due to prolonged school closures caused by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Related Articles: