The Great Pacific garbage patch is a collection of plastic and floating trash with two enormous masses of ever-growing garbage. The patch consists of finger-sized bits of plastic – often microscopic particles, chemical sludge, wood pulp, and other debris trapped by the northern circulating currents of the Pacific Ocean known as the North Pacific Gyre.

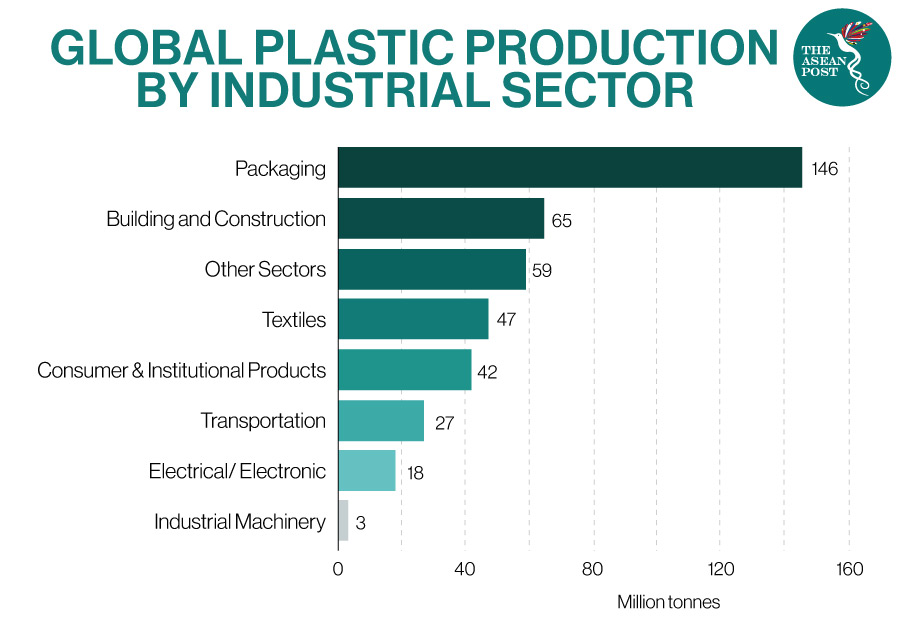

The plastic concentration is estimated to be 100 kilograms per square kilometre. The patch currently covers 1.6 million square meters. Approximately 100 million tons of plastic is generated globally each year, of which 10 percent ends up in the world’s oceans according to the United Nations Environment Program (UNEP).

The problem has now been further exacerbated by the coronavirus pandemic as “a new wave of plastic pollution” is littering beaches and public spaces in the form of disposable masks and gloves, said Jack Middleton from Surfers Against Sewage, a movement tackling plastic pollution.

With even the first world struggling to manage its waste, the only available solution is to halt the use of plastic as widely as possible. Critics have argued that this is easier said than done. However, action against pollution is always a matter of bearing unwanted costs for the greater good – not easy but possible.

Back in 2017, a report by the Ocean Conservancy named four ASEAN member states among the top plastic polluters in the world – namely Indonesia, Thailand, Vietnam and the Philippines. Each country has since taken up individual efforts to address the issue – some faster than others.

Most notably, Thailand has effectively enforced new policies, with three types of single-use plastic being banned in 2019. The Thai government developed a Plastic Waste Management Road Map 2018-2030 to end the use of single-use plastic and to repurpose plastic waste as a source of fuel. This strong commitment can be attributed to a string of incidents in southern Thailand that have led the once "plastic addicted" nation to now set an example for the rest of ASEAN.

In February 2018, a patch of plastic trash almost 10 kilometres in length was sighted floating off the coast of the Gulf of Thailand in the southern province of Chumpon. Just three months later another eye-opening event happened in the southern province of Songkhla when a dead whale was found to have swallowed 80 plastic bags.

These incidents have made Thais in general more dedicated to the cause – addressing the matter beyond the normal analysis of cost and benefit.

Indonesia – a country listed as the second worst offender for polluting the world’s oceans with plastic – started banning single-use plastics in July 2020. However, when the ban was first implemented, media reports stated that it failed to gain much traction.

The regulation requires shops and stalls to provide environmentally friendly bags on pain of written warnings, hefty fines, then suspension or rescinding of permits.

“It’s a good idea to reduce plastic bag usage, but it needs to be more intensely communicated to encourage people to bring their own bags,” said an Indonesian shopper Farhan Ahmad to the media.

Plastic Free Hospitality

Southeast Asian countries cannot afford to wait for their respective governments to take action and solve the plastic crisis. The corporate sector has to be responsible too and take active action against environmental pollution. They can help to offset the financial cost normally associated with clean-up drives or awareness campaigns. Businesses generally have the capacity to make a larger, more positive impact.

One example is the hospitality sector. In 2019, popular tourist destination, Bali had to declare a “garbage emergency” due to massive amounts of plastic washing up on a six kilometre stretch of its beach. Consequently, there is now a global effort to drastically reduce plastic waste in hotels.

International tourism advisory group, EarthCheck, introduced a certification scheme for hotels that qualify as eco-friendly. The Banyan Tree Samui became the first hotel in Thailand to be awarded its “Gold Certification”.

In place of plastic came glass bottles, paper straws, bamboo and wooden cutlery, and corn-based toothbrushes. They ordered biodegradable bags and containers, and large second-hand rice and sugar sacks for the kitchens and for garden waste. Unable to find an environmentally friendly alternative to cling film, they set a strict budget on its purchase.

“Attaining EarthCheck Certification is not an easy task,” said Stewart Moore, CEO and founder of EarthCheck. “It requires commitment from the entire team to achieve better results in terms of sustainability each year. The challenge is to continually prove the integrity of an organisation's operational practices and then be willing to have everything checked and measured by an independent third party.”

With more people opting for environmentally friendly services, it is also within the interest of businesses to act on this threat.

Related Articles: