According to the Tapir Specialist Group, an organisation that works to conserve their habitat – tapirs are living fossils. The creature has been around since the Eocene period, which was about 33 to 56 million years ago and have survived waves of extinction as opposed to many other animals.

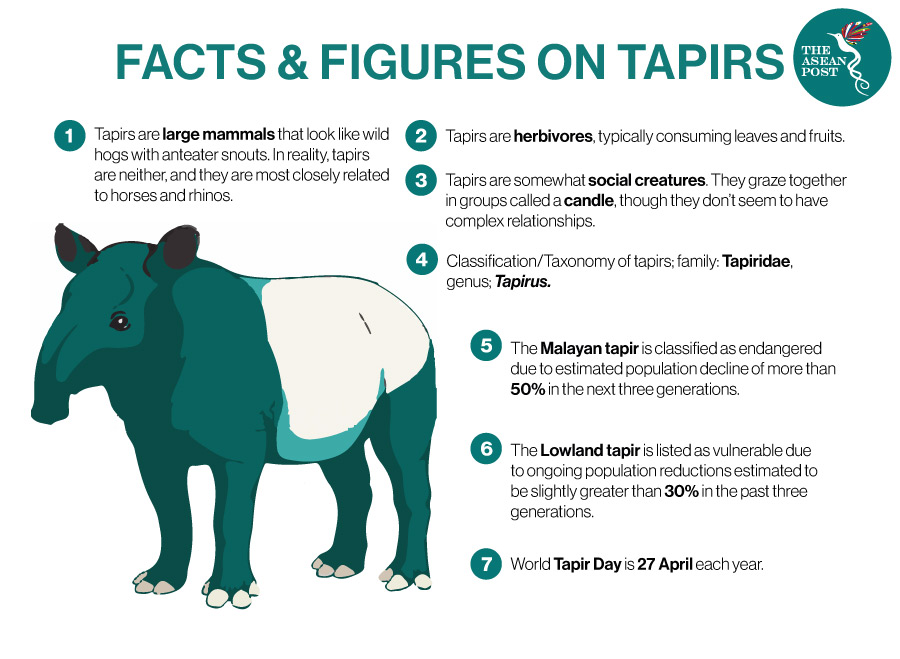

They are often confused with large mammals such as hippos, pigs or anteaters, but their closest living relatives are actually rhinoceros and horses.

One of the tapir’s major roles in nature is in the dispersing of seeds. Tapirs are known herbivores and eat a variety of seasonal fruits. They can typically be found underneath trees, eating the fruits that fall from them. The seeds in the fruits they eat are then dispersed when they go to a new location to deposit scat. These seeds would later sprout and grow into new trees, according to the Tapir Specialist Group.

There are only four types of tapirs remaining in the world – the lowland tapir, mountain tapir and Baird’s tapir, which are found in Central and South America. Whereas the Malayan tapir – the largest of the four, is the only surviving member of its species in Asia.

The Malayan tapir can be found in the wild mainly in Malaysia, Indonesia, Thailand and Myanmar. Unfortunately, their numbers are continuously dwindling. It was reported that there are about only 2,000 to 3,000 Malayan tapirs left in the world.

In 2008, the conservation status of the species was elevated from “vulnerable” to “endangered” on the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List of Endangered Species.

Brink Of Extinction?

According to the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), the main threat to Malayan tapirs is human activity such as deforestation for agricultural purposes, flooding caused by the damming of rivers for hydroelectric projects, and illegal animal trade.

Dr Alan Shoemaker from the Tapir Specialist Group explained that the declining number of Malayan tapirs is because of continued habitat loss from illegal logging and the lack of protection in most areas where the animal is known to reside.

The iconic animal in Malaysia is a fully protected species under the Wildlife Act 2010. However, the population of the Malayan tapir has also declined in the country because of the loss of their forest habitat and in recent years due to the growing number of deaths as a result of roadkill.

According to Malaysia’s Department of Wildlife and National Parks (Perhilitan), in 2017, a total of 25 tapirs died after being hit by vehicles. Statistics from Perhilitan show that 2,444 wild animals died as a result of roadkill from 2012 to 2017 despite signboards placed at areas known for wildlife crossings. The rampant hit-and-run cases involving Malayan tapirs have even garnered the attention of local politicians and non-governmental organisations (NGOs).

In early 2020, an NGO based in the southern state of Johor in Malaysia, Pertubuhan Sahabat Alam Sekitar Kluang (Kluang’s Friends of Nature) lodged a report requesting authorities to look into the death of a female tapir which was believed to have been hit during an illegal motocross racing event in the area.

Biological Conservation, a peer-reviewed journal of conservation biology, published a paper titled, ‘Two species, one snare: Analysing snare usage and the impacts of tiger poaching on a non-target species, the Malayan tapir’, which claims that areas with high frequency of tiger evidence also showed high frequency of tapir evidence. The two mammals tend to favour the same network of trails through the forest. However, tigers are the least of the tapirs’ worries.

Unfortunately, the illegal trade in tiger bones and body parts has threatened the population of Asia’s tigers. But this grisly business is also harmful to other species that have the misfortune of being caught in snares, according to NGO, Fauna and Flora International. Poachers are typically opportunists. While tigers are their main target, they won’t hesitate to capture other animals if they are found trapped in their nets – and sell them for bush meat.

There have been a number of reports where Malayan tapirs are accidentally killed by hunters and poachers. The Malayan tapir has poor eyesight and is generally active at night. They are more vulnerable to traps and snares than other wild animals.

As the Malayan tapir reproduces slower than most mammals with pregnancies lasting as long as 14 months – the task of conserving this animal will surely be a challenge. Nevertheless, Malaysia remains hopeful as its Department of Wildlife and National Parks (Perhilitan) announced in 2019 that the country will build Malaysia’s first tapir conservation centre which will focus on tapir rehabilitation and a breeding programme.

Will the Malayan tapir survive for future generations to see this magnificent animal or will it face the same fate as other species that have already gone extinct?

Related Articles: