Last year, the world witnessed a number of animals that went near or completely extinct. This includes the Chinese paddlefish, the Sumatran rhino and the Indochinese tiger – which is extinct in the wild but a rare few are still living in captivity. Malaysia’s last Sumatran rhino named Iman died in November 2019, making the extremely endangered species locally extinct. It was reported that there are now less than 80 of these rhinos left all over the world, a majority of them currently in Indonesia.

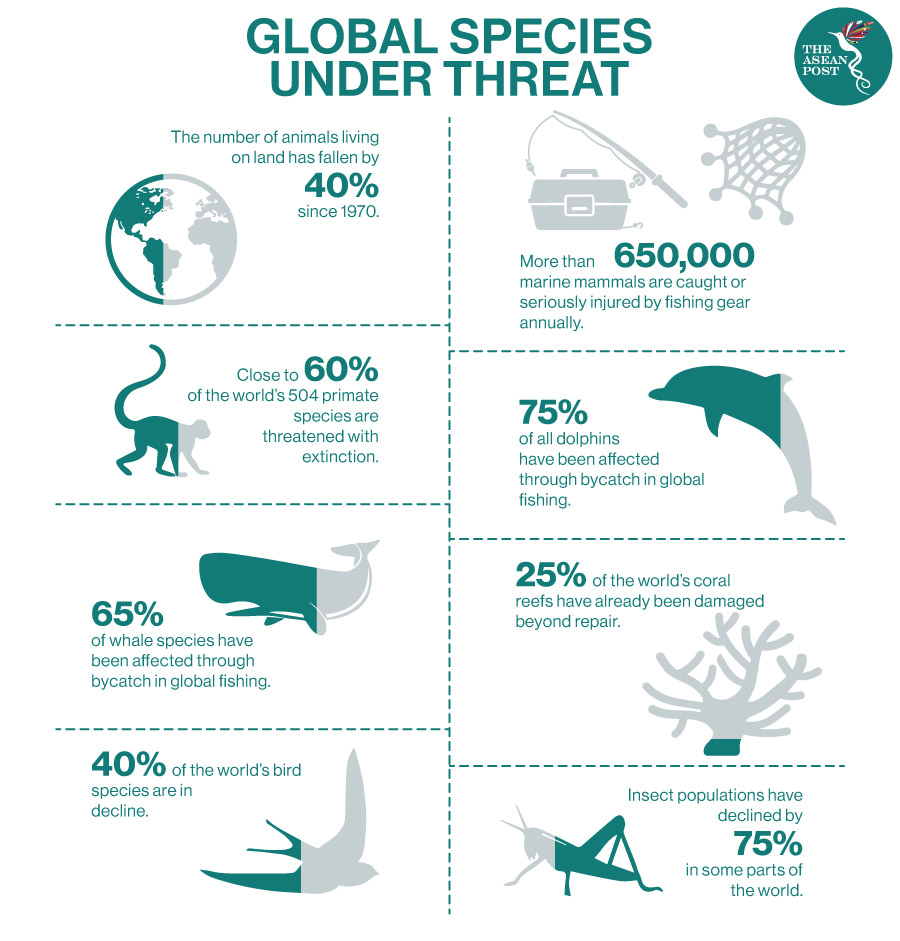

According to the United Nations (UN), nature is declining globally at rates unprecedented in human history, and the rate of species extinctions is accelerating. Around one million animal and plant species are now threated with extinction. Experts say that by 2100, an estimated 50 percent of all the world’s species could go extinct because of climate change.

“Ecosystems, species, wild populations, local varieties and breeds of domesticated plants and animals are shrinking, deteriorating or vanishing. The essential, interconnected web of life on earth is getting smaller and increasingly frayed,” said Professor Josef Settele, at the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES), while co-chairing an assessment on biodiversity and ecosystem services.

“This loss is a direct result of human activity and constitutes a direct threat to human well-being in all regions of the world,” he added.

Global warming has become a major driver of wildlife decline. And when combined with other human activities that are detrimental to the environment – it is pushing a growing number of species closer to extinction.

A research published last week in the journal, Nature Climate Change, titled 'Fasting season length sets temporal limits for global polar bear persistence', suggests that polar bears will vanish from the face of the earth in 80 years if greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions remain at their current levels. Scientists say that some populations have already reached their survival limits as the Arctic sea ice shrinks.

“Polar bears have become the poster species for climate change because their survival is linked to sea ice, which they use as platforms to hunt for seals,” said Victoria Gill, a science correspondent from a British news agency.

Media reports have stated that the melting rate of sea ice in the Arctic has increased 13 percent per decade since data collection with satellites began in the 1970s.

Unfortunately, polar bears are not the only species facing possible extinction. It was reported that most of Southeast Asia’s large-bodied animals are now endangered.

Extinction Crisis

The saola, also known as the Asian unicorn is one of the world’s rarest large mammals, and found only in the Annamite Range of Vietnam and Lao PDR. It was reported that the last photograph of the species was captured around seven years ago in Vietnam.

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) stated that there are “undoubtedly less than 750, and likely much less” of the species in the world with experts believing that there may be fewer than 100 left.

Other than that, the great apes of Southeast Asia, said to be the most endangered ape species, are at risk of extinction due to deforestation. And the list goes on: elephants, tapirs, Yangtze giant softshell turtles, and Philippine crocodiles, among others.

Big mammals are not the only ones threatened in the region. Innumerable turtle species are being wiped out for food and traditional medicine. Birds such as the endangered Brazilian spix macaw are hunted to be eaten or traded as illegal pets. Malaysia’s Precious Steam-Toad was also listed as vulnerable as development threatens the species’ habitat.

According to Mongabay, an environmental science and conservation information platform, the reasons Southeast Asia is “facing an extinction crisis” are varied and unique to each country. Nevertheless, the number one cause could be pointed to deforestation.

Southeast Asia is home to almost 15 percent of the world’s tropical forests. However, the region is also known for its alarming rate of deforestation. According to Valerio Avitabile, a scientist at the Joint Research Centre (JRC) – a European Commission science and knowledge service, the region lost about 80 million hectares of forest between 2005 and 2015. It is feared that deforestation could lead to over 40 percent of Southeast Asia’s biodiversity vanishing by 2100.

“By 2050, Southeast Asian forests may shrink by 5.2 million ha (hectares) or grow by 19.6 million ha, depending on which pathway we will take,” said the scientist.

Illegal wildlife trade for traditional medicine, bushmeat, pets and trinkets could perhaps be one of the reasons for Southeast Asia’s declining wildlife. Stories of animals being hunted and killed for parts or trapped in snares to be sold are not unheard of in the region.

If Southeast Asia is not serious in preserving its unique and irreplaceable biodiversity, the losses will continue to mount.

Related Articles: