Cyclones, earthquakes, economic crises, and epidemics are business risks companies have been facing for decades. The COVID-19 pandemic has hit global supply chains at an unprecedent scale and speed. In Asia, the lockdowns have caused the closure of businesses, stoppage of factory outputs, and disruption to manufacturing industries and their supply networks.

Since the 1980s as globalisation deepened, an increasing number of firms, particularly small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in ASEAN, participated in global supply chains typically at the intermediate and final assembly stages. ASEAN and East Asia’s export-oriented open trade policies have contributed to the birth of these value chains and the accompanying high economic growth.

Nevertheless, these complex supply chains are inherently vulnerable to external shocks and disruption. Asia’s unique vulnerability to climate change, disasters, and diseases means that building resilience is a business continuity issue for every company along the supply chain. All Asian countries fared poorly in the 2020 World Risk Index on strengthening their abilities to prepare and adapt to extreme events.

However, a recent Economic Research Institute for ASEAN and East Asia (ERIA) study on supply chain resilience that explored the vulnerability of businesses to unpredictable risks found that companies are now much more concerned about external uncertainties than in previous decades.

The COVID-19 pandemic is putting Asia’s supply chains to the test; firms need to assess their corporate risks and build resilience. Combined with the financial impact of a global economic downturn, supply chain resilience is crucial for the survival of individual companies.

Short term measures

A good resilience strategy can achieve both the short-term goal of safeguarding business operations, while working with governments toward the long-term goal of building resilient economies. Several natural disaster events in the last two decades have caused short-term supply shocks, however they have not reduced operational capacity of firms, and exports bounced back more quickly than expected.

Those crises have not reversed the patterns of globalisation but accelerated two long-term trends in the global supply chain. First, leading firms used the crisis to consolidate their supply base further by institutionalising Business Continuity Plans (BCP), a corporate strategy that promotes a strategic buyer-seller relationship, to ensure continuity of operations with minimal service outage and to act as a source of resilience.

Second, when demand rebounds after a crisis, the growth of intra-regional trade creates opportunities for new firms to upgrade to global value chains. While firms are responsible for addressing supply and demand shocks with appropriate corporate insurance mechanisms, a multi-stakeholder approach of adopting BCPs that involves government support for early warning systems, information sharing, capacity building, and technical support are important approaches to enhance supply chain resilience.

Recovery, Resilience And Competitiveness

Medium term actions for enhanced resilience include better understanding and managing the supplier networks, increasing production efficiency, and systematically developing strategic changes to harness potential new markets.

A prolonged pandemic or deeper structural impacts could delay the recovery of firms by returning them to their pre-COVID supply capacity. In the 1997 Asian economic crisis, a liquidity problem, and a collapse of demand in some major economies rippled down along selected value chains, but many companies recovered quickly with banking sector support, resulting in full recovery within a year or two.

But the COVID-19 pandemic is of higher magnitude and has dramatically increased a range of pathways that firms, particularly small businesses, could take to encompass multiple risks along the global supply chain.

During the 2008 global financial crisis, the fall in global demand was accompanied by a drop in demand for intermediate goods destined for assembly in China, Korea, and Japan. Due to heavy reliance on imported inputs from Singapore, Malaysia, Indonesia, Thailand, and Vietnam, they effectively transferred a large portion of its negative export demand shocks to their ASEAN partners.

Although export-centred economic growth has largely been a story of rising Asian companies’ supplier capabilities, there has been growing recognition of the key role that final export markets play in the process.

Companies that sell their products to advanced economies like Japan, the European Union (EU) and the United States (US) should be aware of new opportunities for green growth which have been invigorated by the pandemic recovery stimulus packages.

While consumer demand will return slowly, prices will remain an overwhelming consideration in the post pandemic era.

New Resilient Supply Chain Models

Enhancing the resilience of firms in the longer-term involves building new digital infrastructure and joining international agreements on industry-wide standards.

More than three decades of focus on optimisation to minimise production costs, reduce inventories, and drive up capital utilisation has resulted in lean global supply chains, thus removing buffers and flexibility of Asian companies, particularly small businesses, who are no longer able to absorb disruptions. The pandemic many lead companies to rethink and transform these lean production networks.

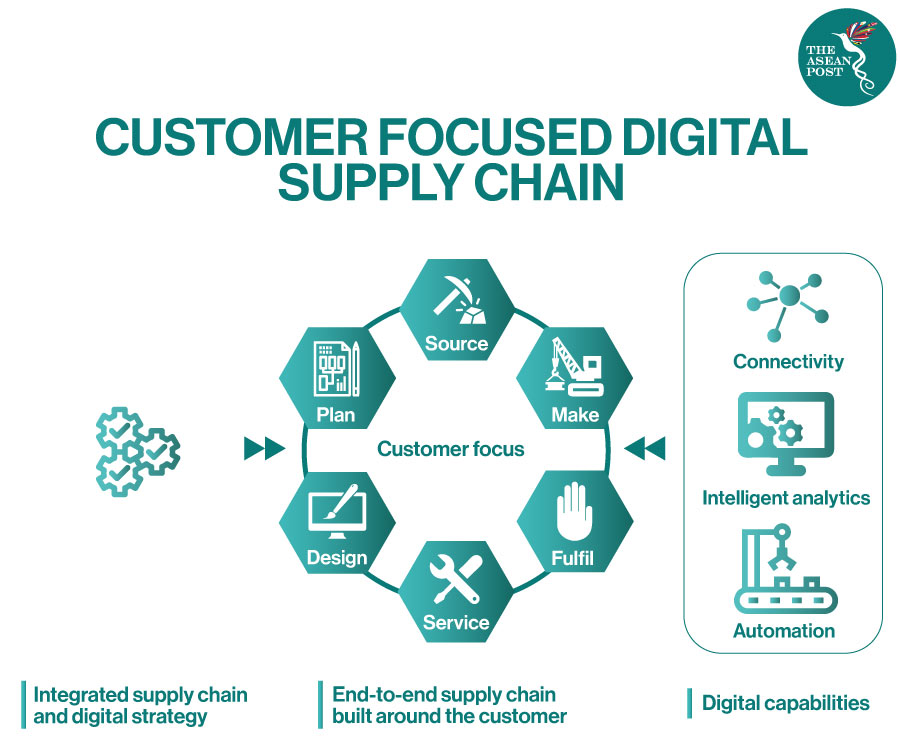

Fortunately, new technologies are emerging, which could dramatically improve resilience and competitiveness. The traditional linear supply chain model is transforming into digital production networks, where functional silos could be broken down and organisations can become connected to their supplier networks to enable end-to-end traceability, collaboration, agility, and cost optimisation.

Leveraging advanced digital technologies such as the internet of things (IoT), artificial intelligence (AI), robotics, block chain, cognitive computing, augmented and virtual reality help to anticipate and meet future competitive and resilience challenges. Keeping the competitiveness in global supply chains requires investment in people, skills and high-quality digital infrastructure and encouragement of strong industry-university linkages.

The Sendai Framework, a non-binding international agreement by the United Nations (UN), and the ASEAN Agreement on Disaster Management and Emergency Response (AADMER) recognise the private sector as a key stakeholder, responsible for building businesses that make risk- informed decisions and develop resilient supply chains.

Committing to such international agreements will be a significant modifier for companies to collectively act on industry-wide resilience standards. Consciously building resilience will be the better recipe for long-term competitiveness of firms.

Related Articles: