Around the world, scorching heat waves are breaking records, with France reaching a sweltering 45.9 degrees Celsius and Australia hitting 49.5 degrees in 2019. This year, it was reported that Siberia experienced a period of unusually high temperatures for the first six months of 2020 – including a record-breaking 38 degrees Celsius in the town of Verkhoyansk last June. Whereas most of the United States (US) is expected to be hit by a massive heat dome with higher than 32-degree temperatures this weekend.

Based on simulations conducted at the Centre for Climate Research Singapore, the country can expect to face soaring temperatures of 40 degrees Celsius, as early as 2045. Over in Malaysia, the Malaysian Meteorological Department (MetMalaysia) warned of higher temperatures from February this year up to mid-April, with northern states of the peninsula to feel more heat.

“Temperatures in these areas may sometimes reach up to 37.5 degrees Celsius,” it said in a statement. In February 2019, Malaysia was gripped with a heatwave. Although hot weather is a normal phenomenon in the region, the MetMalaysia issued a ‘Level 1’ alert to at least 10 areas where temperatures hit 35 to 37 degrees Celsius for three consecutive days.

Rising outside temperatures are driving an increase in demand for air-conditioners (ACs). Based on the Future of Cooling 2018 report by the International Energy Agency (IEA), around two-thirds of the world’s households could have ACs by 2050. China, India and Indonesia will together account for half of the total number of units for that year.

Still, Singapore has the highest installed rate of ACs per capita, according to a 2017 study by the National Environment Agency. Based on the same study, 24 percent of electricity consumption is for ACs in a typical home.

Trapped Heat

The Climate and Clean Air Coalition, a voluntary partnership led by governments, intergovernmental organisations, NGOs and civil society actors has stated that hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs), which are synthetic greenhouse gases (GHG) used in ACs, are growing at a rate of eight percent per year due to the increasing use of ACs. HFCs may represent a small portion of total GHG emissions, but they trap thousands of times as much heat in the atmosphere as carbon dioxide (CO2).

Together with the IEA, researchers at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and Rocky Mountain Institute (RMI) concluded that room ACs alone – the typical window and split units used in most homes – are set to account for over 130 gigatons (GT) of CO2 emissions between now and 2050.

HFCs can enter the atmosphere during the manufacturing process, when the air-conditioning unit has a leak, and until the unit is thrown out. Proper disposal of ACs is also important. Unless HFCs are regulated, the projected consumption will double by 2020 which could significantly contribute to radiative forcing in the atmosphere by 2050. Environmentalists, government officials and scientists say an agreement to limit HFCs represents a significant step in the fight to stave off the worst effects of global warming.

Soaring Demand

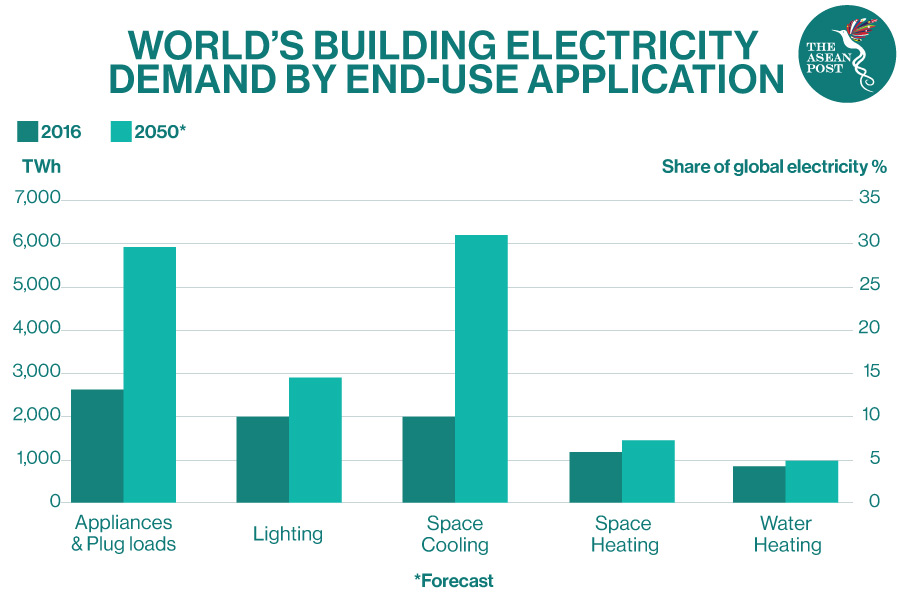

The use of ACs is set to soar, driving the global electricity demand by 2050. Currently, ACs account for 10 percent of global electricity demand. According to the IEA, global use of electricity will grow in parallel with the increased use of ACs to become the largest user of electricity in buildings, accounting for 16 percent of global electricity demand in 2050.

Air conditioners have always been considered a luxury item. But with the rise in global temperatures as well as the growth of the affluent middle class, more people are buying AC units today. The sweltering heat is no longer just uncomfortable, it can prove lethal, especially to vulnerable groups such as infants, the sick and elderly.

“Growing demand for air conditioners is one of the most critical blind spots in today’s energy debate. Setting higher efficiency standards for cooling is one for the easiest steps governments can take to reduce the need for new power plants, cut emissions and reduce costs at the same time,” said Fatih Birol, Executive Director, IEA.

Southeast Asia already uses about 60 percent of its electricity for ACs alone according to a 2018 white paper by Eco-Business Research and the Kigali Cooling Efficiency Program (K-CEP). The widespread availability of ACs has allowed for more development, leading to higher AC usage in the region. With increasing demand, the efficiency of air-conditioning units is key for Southeast Asia to control the negative impacts ACs have on the environment.

However, public awareness in the region about the environmental impact of ACs remains low. Government policy and regulation should help increase understanding and awareness of the negative impact of ACs. Educating consumers with easy to read manuals on efficient usage can also help reduce power wastage and reduce carbon footprints.

Related Articles: