The plight of the “boat people” has come to the attention of the international community for a long time now. The world thus far has reacted to this cataclysmic humanitarian crisis that is even said to be tantamount to genocide. Countries and peoples of the world as well as the United Nations (UN) are calling for humanitarian interventions to save and rescue these “boat people” who are suffering from all sorts of human atrocities and are in such dismal condition.

Without a doubt, the quandary of these “boat people” – the Rohingya – is heart-breaking and needs global attention now more than ever, especially in this time of the COVID-19 pandemic.

However, providing humanitarian assistance, and even accepting these “boat people” as refugees or asylum seekers in third countries will only serve as a short-term solution and would not resolve the issue at its core. All these forms of assistance will not necessarily resolve the influx of refugees or the exodus of the Rohingya from Myanmar in their bid to escape persecution and the gloomy situation in their homeland.

Status Of Statelessness

Rather, this migratory crisis will continue until the root cause of the problem is arrested. On this note, it is but a must that, while humanitarian assistance and aid are extended to the “boat people”, and while they are being offered a safe temporary haven in third countries – the international community, especially ASEAN member states, must make a concerted effort to address its root-cause; the “” of the Rohingya in Myanmar coupled with extreme cultural, political and economic discrimination against them.

The issue of the Rohingya is thus far an issue of “statelessness”. Statelessness is an issue that has left a smudge on Southeast Asia at the end of the colonial period. Many minority groups in the region do not have the legal attachment of nationality with any state and one of these minority groups is the Rohingya.

The Rohingya are a group of Muslim people living in the northern part of Rakhine State who are ethnically, linguistically, and religiously distinct in Myanmar. They are not considered citizens or nationals of Myanmar. This came about when the new nationality law was passed in 1982. The Rohingya were not included among the 135 national races that were granted full citizenship. They are considered both, by the government of Myanmar and by a large part of the Buddhist population of the country to be “illegal migrants” and “Bengalis”. Sadly, even Bangladesh does not consider the Rohingya as their own which makes the plight of these people even more perilous.

The statelessness of the Rohingya poses a serious impediment to their fundamental rights. In the case of the Rohingya, they are consistently subjected to stigmatisation, harassment, isolation, deprivation, starvation, and are restrained from having access to basic social services. The on-going extreme discrimination and persecution has already reached unprecedented heights, and considered an act of genocide already, leading to the Rohingya being forced to flee their homes and country on boats.

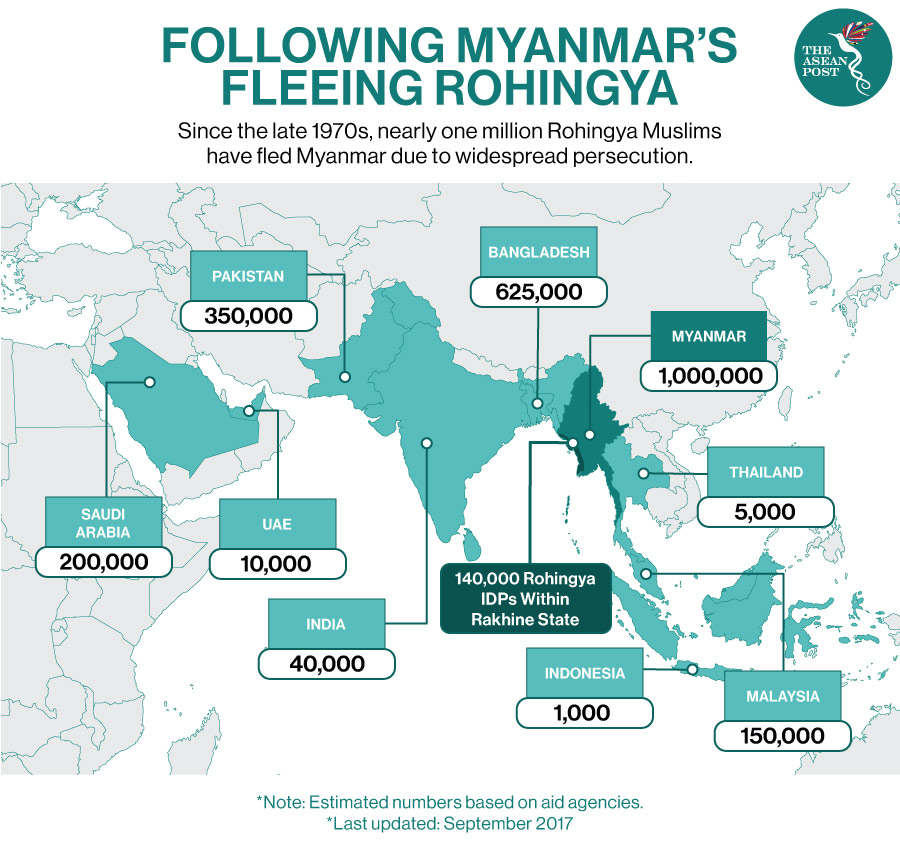

All this has resulted in the massive displacement and migration of the Rohingya, with many of them stranded in the Andaman Sea, while others seek refuge in third countries which in most cases are reluctant, or not at all accommodating when the Rohingya disembark on their respective coasts.

This scenario, to some extent, is straining inter-state relations in ASEAN and beyond, due to the spill-over effect. Thus, the plight of the Rohingya, is no longer just a domestic issue in Myanmar but a problem that needs a regional solution and intervention.

In the context of Southeast Asia, migration and statelessness are in many ways very much interconnected. Statelessness in most cases has been both, a cause and a consequence of the movement and displacement of people in the region. The issue of statelessness as a consequence and a cause of migration is a socio-political countenance in ASEAN that needs to be confronted if the region wants to make its vision of people-centred regional integration a reality.

Myanmar Must Do Its Part

Thus, the crux of the problem is the two-some quandary of the status of statelessness of the Rohingya, and the extreme discrimination they face. And since Myanmar is central to this problem and at the same time the key to the resolution of this humanitarian crisis, the international community must ensure that Myanmar does its part.

Myanmar must address the issue of statelessness of the Rohingya if the plight of the “boat people” is to be resolved. There is simply no other way. Addressing statelessness can to a greater extent facilitate deterrence and preclusion of massive forced displacement, veer social tension, and boost human capital. The recognition of this problem by the government of Myanmar, coupled with pressure from the international community, can serve as stimuli for all these actors to devise practical strategies and solutions.

For the Myanmar government, it is not enough to make pronouncements telling the world that it will provide humanitarian assistance to these “boat people”. As a responsible and compassionate government, it should integrate the Rohingya as one of the ethnic minorities in Myanmar, and as citizens of the country. The Rohingya should be given proper identification and be documented.

Only by doing so can the Rohingya enjoy their fundamental rights; while the extreme discrimination experienced by them will be lessened to a considerable degree or ceased completely. Likewise, the massive humanitarian crisis of the “boat people” will truly be addressed and the migration of Rohingya as a consequence of their statelessness will to a considerable degree be reduced or even eradicated.

The Rohingya have a fundamental right to a nationality, and this right is incorporated in almost all major and contemporary human rights instruments as enthused by Article 15 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR). Concurring with international law, the Myanmar government is obligated to address the issue of statelessness of the Rohingya if it wants to gain the recognition of the world as being sincere in its vision of transforming the country into a truly democratic state.

For third countries like Thailand, Malaysia, Indonesia, and Bangladesh, as they continuously face the massive influx of migrant Rohingya seeking solace and assistance along their shores, it is but of the essence that these countries recognise these people and offer them temporary shelter and abode until their situation is improved. This is what protection and promotion of human rights truly mean.

Following their human rights obligations, and under international law, states bear the responsibility to protect the fundamental rights of all persons within their jurisdiction, including those who are stateless, without discrimination.

Related Articles: