Lily (not her real name), a Malaysian woman in her late 20s, told The ASEAN Post that she once took a Grab ride for a short 10-minutes journey from her apartment in Petaling Jaya, a city in the state of Selangor to a train station nearby her home. The Grab driver was a cheerful, slightly older man who made decent conservation with Lily throughout the ride.

However, not long after she got out of the car and they bid goodbye, Lily started receiving “uncomfortable” messages from the Grab driver. This was around three years ago before the ride-hailing company introduced “number masking” which allows customers to mask their phone numbers for greater privacy and security. The feature also allows for completely anonymous calls between drivers and passengers.

“It wasn’t anything threatening, he just asked if we could be friends,” said Lily. “I wasn’t comfortable because he knew where I lived and had my number.”

Despite safety features incorporated in ride-hailing apps – stories such as Lily’s are still being recorded frequently everywhere.

Recently, it was reported that Foodpanda in Malaysia, a mobile food delivery marketplace, is looking into complaints made by a woman claiming that a delivery man had been harassing her to spend time with him.

“Hello @foodpanda_my, do something about your rider. This is super scary and inappropriate. Where are his ethics? Asking his customers if they want his company in their homes. For girls out there, be careful if you get a rider like this,” tweeted the victim, Mia Azahar.

She also shared text exchanges between the delivery man and herself. According to the screenshots, the man had just dropped off her food order and was sending her messages from outside her home, asking whether she wanted company.

“The panda rider from just now. I’m still downstairs. Can I come up, or should I leave?” one of the messages reads.

This is not the first time the food delivery app was roped in a harassment allegation. A few months ago – back in August to be exact – a Singaporean woman, who only wanted to be known as Miss Qiao reported that a Foodpanda delivery man entered her home without permission and also harassed her by asking her for sex.

A Foodpanda spokeswoman responded to the incident by clarifying that the delivery man has been blacklisted and the company “place the safety of our customers as a priority and take a zero-tolerance stance on harassment in any form,” she told the media.

In September 2020, a former Grab driver in Singapore claimed trial to sexual assault and attempted rape of a 19-year-old passenger he picked up from a bar two years prior. In another incident reported in 2018 in Indonesia, this time on Gojek, a 28-year-old victim ordered a Go-Car from Jakarta’s Soekarno Hatta International Airport. She fell asleep in the car and woke up to find the driver groping and attempting to rape her.

These incidents are not just exclusive to Southeast Asia. It happens everywhere around the world. In 2018, Uber reported over 3,000 sexual assaults during its rides in the United States (US), with nine people murdered and 58 killed in crashes.

Moreover, a 2019 Uber Safety Report found that female drivers also experienced sexual harassment and abuse at similar rates as passengers. Similar cases regarding assault against drivers could also be seen in Southeast Asia. For instance, in 2018 in Singapore, a passenger was sent to jail for more than five years for molesting his Uber driver while she was driving.

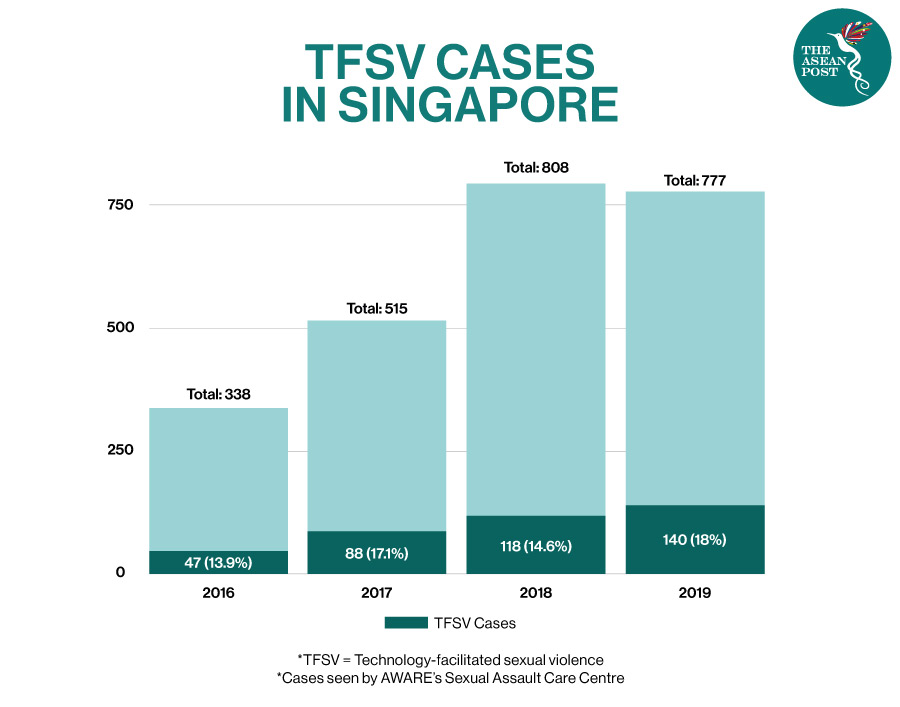

According to AWARE, a women’s rights and gender equality group in Singapore, its Sexual Assault Care Centre (SACC) has seen the number of technology-facilitated sexual violence (TFSV) cases triple across four years. AWARE defines TFSV as unwanted sexual behaviours carried out via digital technology such as digital cameras, social media and messaging platforms, and dating and ride-hailing apps.

The SACC said that in 2019, 21 cases were reported in the island-state involving sexual abuse facilitated by dating or ride-hailing apps.

Safety Measures

Over the last few years, ride-hailing companies have implemented several policies and features to address sexual harassment.

Other than the aforementioned number masking, Grab has also introduced a feature in Southeast Asia that allows passengers to notify security should something happens and share their ride trajectory with emergency contacts.

Moreover, Gojek in 2019 allowed its drivers in Singapore to opt for the installation of inward-facing recording devices in their vehicles. Recordings are stored for a week and can be accessed by authorised data controllers in cases of dispute, informed Shailey Hingorani from AWARE in her article titled, “Does the ride-hailing industry have a sexual harassment problem?”.

Whereas in Malaysia, a women-and-children-only transportation and delivery service called RidingPink was launched a few years back. Women-only ride-hailing services have also been introduced in other parts of the world. The move is reminiscent of dedicated women-only public transportation such as on trains in various countries.

Nevertheless, “despite efforts at making ride-hailing services safer for all, more can be done to improve safety for passengers and drivers,” said Hingorani.

Related Articles: